How Stephen Decatur Thwarted Pirates and Became an Early American War Hero

A painting of Lt. Stephen Decatur during a boarding operation against a Tripolitan gunboat on Aug. 3, 1804. Wikimedia Commons image.

On the night of Feb. 16, 1804, US Navy Lt. Stephen Decatur entered Tripoli Harbor on a stolen merchant vessel, flying British colors to mask his crew’s intentions. Disguised as Maltese traders, and under the ruse of losing an anchor during an overnight storm, Decatur and his crew secured permission from Barbary pirates to moor alongside the USS Philadelphia, an American frigate that the Tripolitans had hijacked the year prior. While positioned topside, Decatur waited for the right moment to give the signal to a small team of sailors and Marines. At that point the team would swarm the captured frigate and catch its crew by surprise.

The Trojan horse-like infiltration of the Philadelphia would ultimately prove successful — so successful, in fact, that it was later famously described as “the most bold and daring act” of its time. As for Decatur himself, his actions during the raid solidified his place in the pantheon of US naval legends and earned him recognition as one of America’s first war heroes. Given the high stakes of the mission, and the myriad challenges involved, it was a reputation well deserved. Under less capable leadership, the operation could have ended catastrophically and to the great detriment of the US military’s overall mission in the First Barbary War.

In 1803, two years after the United States declared war against the four Barbary states of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, a six-vessel squadron, including the USS Philadelphia, was dispatched to the Mediterranean to protect American shipping interests. The so-called Barbary pirates were a coalition of Muslim buccaneers and English and Dutch mercenaries, who for more than 300 years stalked the coastal waters of North Africa hunting men and supplies to contribute to the thriving slave trade in the region. At the turn of the 19th century, the Barbary pirates began focusing more and more on American vessels because they were no longer protected by British and French naval fleets upon the US Declaration of Independence. In addition to enforcing tariffs on American ships crossing the Mediterranean, the pirates sometimes also boarded the vessels to steal their valuable cargo and capture their crews for ransom.

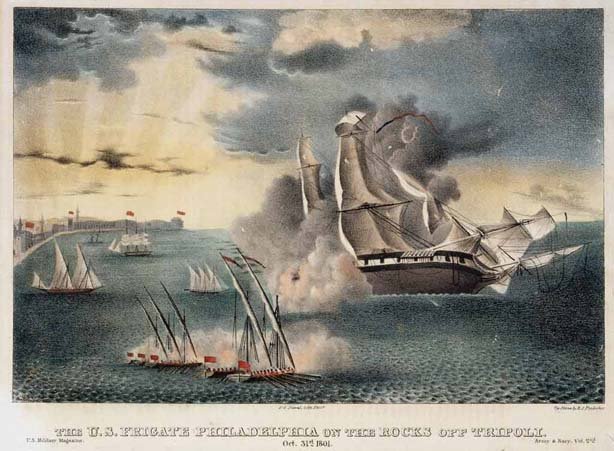

An artist’s depiction of the Philadelphia aground off Tripoli, in October 1803. Wikimedia Commons image.

While the US Navy occasionally engaged in skirmishes with the pirates, relations between the two sides became openly hostile in the fall of 1803 after the Philadelphia ran aground on an uncharted coral reef. The Philadelphia’s skipper, Capt. William Bainbridge, and his 307-man crew worked for hours to dislodge their warship, tossing cannons and weapons overboard to lighten the load so they could escape the dangerous coastline. But as darkness fell, a large force composed of nine Tripolitan gunboats converged on the shipwrecked vessel, and Bainbridge surrendered. The pirates then took the Philadelphia to their buccaneer sanctuary in Tripoli Harbor.

The presence of a captured American frigate was a moral victory for the Tripolitans as well as a major public embarrassment for the US military. Furthermore, the pirates intended to repair the vessel and repurpose it as a gunboat.

Before the pirates could do so, however, Decatur conducted a reconnaissance patrol to scout the harbor and formulate a plan to recapture the Philadelphia. However, he realized that sailing a warship into the enemy harbor would almost certainly be a suicide mission, as it was guarded by more than 100 cannons located on ships and shore batteries. So he decided that, instead of recapturing the Philadelphia, he would take a small skeleton crew into the harbor and set it ablaze.

Thus, a few days before Christmas 1803, Decatur captured the Mastico, a 60-ton Tripolitan ketch armed with four guns. The Mastico looked similar to the hundreds of local ships that passed through the Mediterranean each day. Decatur’s commanding officer, Commodore Edward Preble, commissioned the Tripolitan ketch as the USS Intrepid. They had a month to prepare for the operation. It was decided that the raiding party would carry swords and boarding axes, as pistols and muskets were far too loud for this clandestine mission into the hornet’s nest. Decatur requested that only volunteers should be assigned to the mission since the risk of death was so high.

Stephen Decatur’s Conflict With the Algerine at Tripoli, during the boarding of a Tripolitan gunboat on Aug. 3 1804. Oil over print on canvas, by an unidentified artist, after Alonzo Chappell (1829-1887). Painting in the US Naval Academy Museum Collection. Gift of Chester Dale, 1942. Photo courtesy of the US Naval Heritage and History Command.

“I shall hazard much to destroy her,” Decatur wrote to Robert Smith, then the secretary of the Navy. “It will undoubtedly cost many lives, but it must be done.”

In February 1804, the Intrepid, along with its support vessel, the USS Syren, dropped anchor along the shores of Tripoli to wait out a storm. Then the Intrepid proceeded into the heavily defended harbor. The dilapidated look of the ship proved convincing enough to allow the crew to enter without raising any alarms.

Spotting the Philadelphia, Decatur noticed that all of the hatches were open, displaying its impressive armament of 36 18-pounder guns and 32-pounder carronades. He calculated that about 200 men were needed on board to operate that kind of firepower. In other words, he knew that the enemy crew his sailors and Marines would soon have to overtake was large. They waited until nightfall to commence their assault.

At 10 p.m., as the Intrepid approached within 100 yards of its objective, a lookout aboard the Philadelphia yelled for the ship to halt its approach. A Sicilian pilot aboard the Intrepid — personally recruited by Decatur for his knowledge of the dialect commonly used on the Mediterranean — responded by informing the lookout that the ship had lost anchor in the recent storm. The guard bought the story and allowed the seemingly helpless crew to tether their ship to the Philadelphia. Decatur waited to give his boarding party the signal. Then the Tripolitan blurted out, “Americanos! Americanos!”

An 1897 painting of the burning of the USS Philadelphia. Wikimedia Commons image. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

“Board her, boys!” Decatur shouted as his men flung themselves over their ship’s railing to board the Philadelphia. The boarding party, including Decatur, quickly overwhelmed the shocked pirates and engaged in hand-to-hand combat. Nearby, shore batteries were put on high alert while pirate ships sailed toward the commotion. Once the enemy crew was subdued, Decatur ordered his men to begin the destruction of the Philadelphia. The skipper watched as his men poured gunpowder across the deck and lit oily rags on fire, which they tossed down into gun rooms and onto rigging lines.

As flames engulfed the sails, Decatur ordered the boarding party back to their ship. As the last American to debark the Philadelphia, Decatur cut the mooring lines. The job done, and despite enemy defenses firing away at their fleeing vessel, the Americans escaped the harbor unscathed.

The raid, which British Adm. Horatio Nelson called “the most bold and daring act of the age,” resulted in zero American lives lost. Although Decatur had successfully destroyed the ship, the Philadelphia’s crew remained in captivity until the war ended in 1805. Yet the heroism of Decatur secured his reputation as a leader in the US Navy and he was promoted to captain at the age of 25, becoming the youngest officer to ever achieve that rank. Decatur served in two additional wars after that, including the War of 1812 and the Second Barbary War. He died in a duel with a rival officer in 1820.

Read Next: To the Shores of Tripoli: The Marines’ Daring Raid Against Barbary Pirates

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.