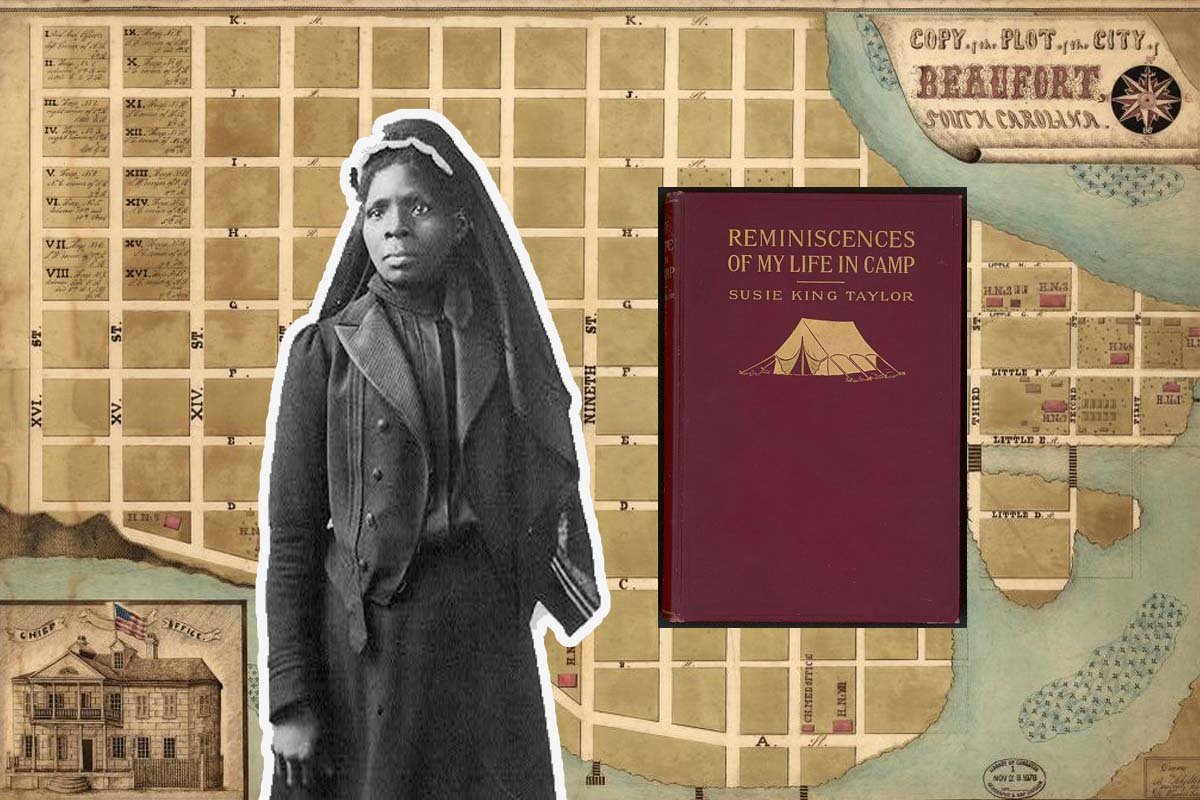

Susie King Taylor was the only Black woman to self-publish a memoir documenting her experiences in the American Civil War. Photos courtesy of the Library of Congress. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Susie King Taylor was the only Black woman to self-publish a memoir documenting her experiences in the American Civil War.

“There are many people who do not know what some of the colored women did during the war,” Taylor writes in her 83-page memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S. C. Volunteers, which she published in 1902.

Though Taylor — who became the US Army’s first Black nurse — gained fame for her wartime experiences and compassion as an educator, the road to achieving those feats wasn’t an easy one.

Taylor was born into slavery as Susie Baker in 1848, and she grew up in Savannah, Georgia, where state laws forbade formal education for Black people. Still, her grandmother arranged for her to secretly attend two “clandestine” schools taught by free Black women and family friends. Her early childhood education made it possible later for her to document the historical roles of enslaved Black women.

When Union Army forces attacked the Confederate-held Fort Pulaski in early April 1862, Taylor and her uncle’s family joined thousands of other Black refugees fleeing by boat to nearby islands in South Carolina. During the journey, she impressed Lt. Pendleton G. Watmough, the commander of the USS Potomska, with her reading and writing skills, and he offered her a teaching position at a children’s school. Thus, Taylor became the first known Black person to teach at a freedman’s school in Georgia. Though just 14, she taught up to 40 children per day, and she even taught adults in extra night classes.

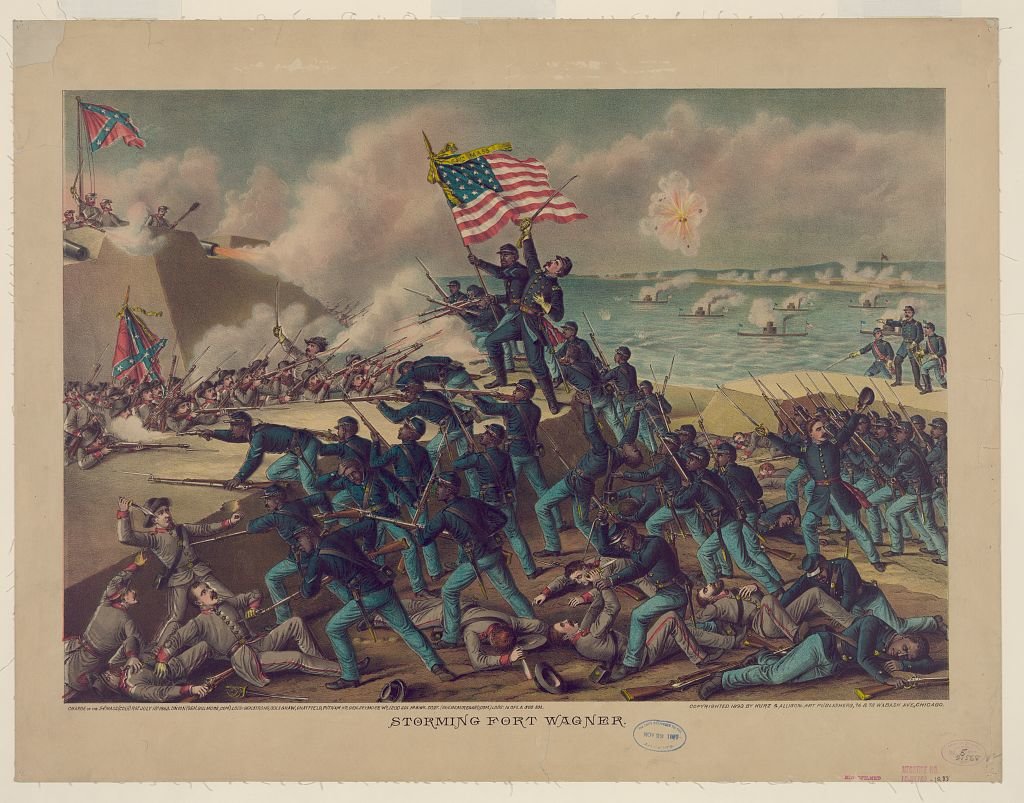

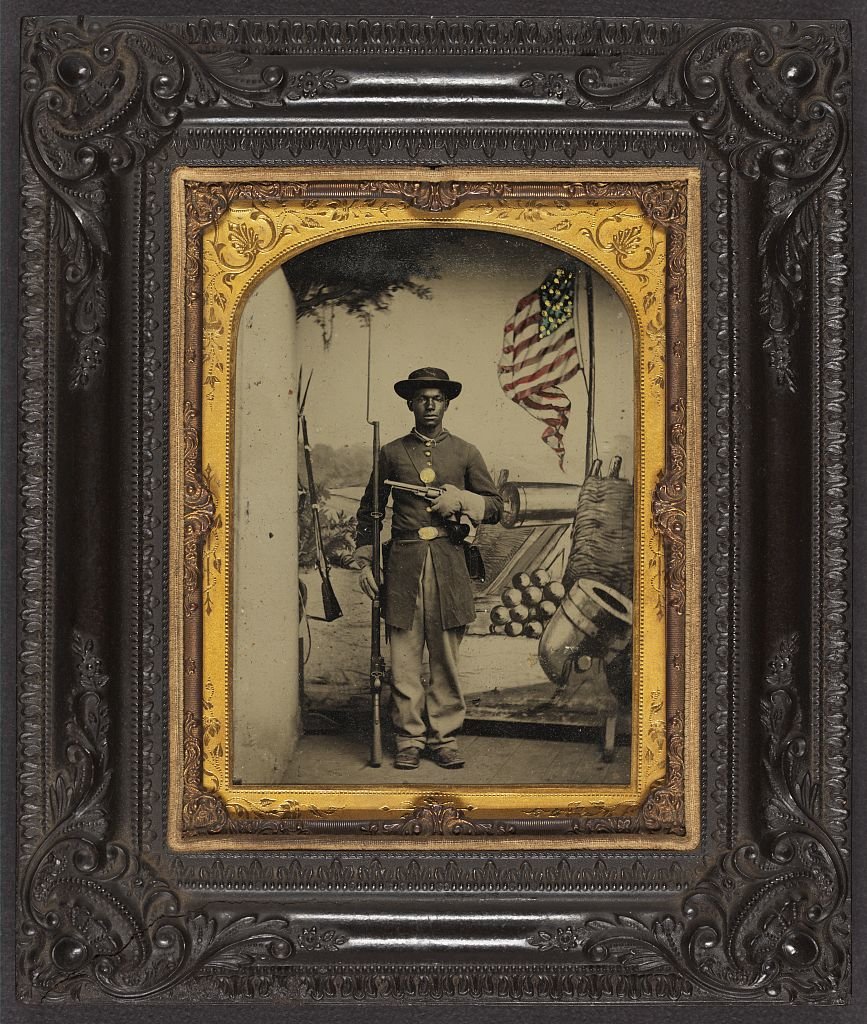

In the fall of 1862, Taylor joined the 1st South Carolina Volunteers — one of the first Black regiments in the US Army — which later became the 33rd US Colored Troops Infantry Regiment, and met her husband, Edward King, in the regiment. With the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Black infantry regiments were awarded stars, stripes, and colors to recognize their roles as soldiers in the Union Army.

Taylor first served in a position referred to as a “laundress,” responsible for cleaning clothes and filling canteens, but she quickly found herself closer to real fighting.

“I was enrolled as company laundress, but I did very little of it, because I was always busy doing other things through camp, and was employed all the time doing something for the officers and comrades,” Taylor writes in her memoir. “I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day.”

She even learned to assemble and disassemble weapons.

Taylor also provided detailed descriptions of battlefield actions and tactics of soldiers she called “her boys” against the Confederates. On one occasion in March 1863, the regiment marched south to Florida, where it encountered Confederate soldiers in blackface.

“They were hiding behind a house about a mile or so away, their faces blackened to disguise themselves as negroes, and our boys, as they advanced toward them, halted a second, saying, ‘They are black men! Let them come to us, or we will make them know who we are,’” she writes, according to the Library of Congress. “With this, the firing was opened and several of our men were wounded and killed. The rebels had a number wounded and killed. It was through this way the discovery was made that they were white men.”

Taylor also supported the regiment with maintaining hygiene and health, working to minimize diseases common in camps, including cholera, malaria, measles, pneumonia, and typhoid. Taylor even met Clara Barton, the founder of the Red Cross, who spoke highly of her fellow nurse during her stay at Camp Shaw.

“It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war,—how we are able to see the most sickening sights, such as men with their limbs blown off and mangled by the deadly shells, without a shudder; and instead of turning away, how we hurry to assist in alleviating their pain, bind up their wounds, and press the cool water to their parched lips, with feelings only of sympathy and pity,” she writes.

In 1864, Taylor’s life nearly ended when her transport ship capsized somewhere in the Port Royal Sound harbor in Beaufort County, South Carolina. Her rescue came on Christmas Day, but she almost died from exposure.

After Edward King died in a docking accident in 1866, Taylor went on to open three schools in Georgia. She married Russell Taylor in 1879, and she dedicated her life to assisting Civil War veterans and their families.

Taylor died in October 1912, a decade after publishing her memoir.

“I wonder if our white fellow men realize the true sense or meaning of brotherhood?” she writes. “For two hundred years we had toiled for them; the war of 1861 came and was ended, and we thought our race was forever freed from bondage, and that the two races could live in unity with each other, but when we read almost every day of what is being done to my race by some whites in the south, I sometimes ask, ‘Was the war in vain? Has it brought freedom, in the full sense of the word, or has it not made our condition more hopeless?’”

Read Next: How the Civil War Created Photojournalism

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.