Holding the Line: America’s Best Technical Rescue Team Is in Small-Town Idaho

Paramedic Chad Smith at the Perrine Bridge in Twin Falls, Idaho. Easy public access to the Snake River Canyon below makes for lots of rescues. Photo by Marty Skovlund Jr./Coffee or Die Magazine.

A base jumper climbs onto a handrail and looks around. Almost 500 feet below is the Snake River, met on both sides by massive sheer cliffs that are stained dark brown by volcanic basalt rock. Behind the man, four lanes of highway traffic roar past, a rushing mix of 18-wheelers, oversize campers, and tourists in rental cars. The jumper is halfway across the Perrine Bridge in Twin Falls, Idaho, probably America’s most wide open and unregulated BASE jumping mecca. The jumper has no permit, hasn’t paid a fee, hasn’t asked for permission, and isn’t worried that a park ranger or cop is about to drive up and stop him.

At the Perrine Bridge, unlike nearly every other well-known BASE jumping spot in the US, you can just show up and … jump.

But this is Idaho. Things are like that here.

A few hundred feet away, at the top of the brown canyon’s cliff face and tied into heavy-duty climbing ropes, Chad Smith briefly looks over at the bridge to watch. He’s seen maybe 1,000 — maybe 10,000 — jumpers make the same leap. Still, he yells out a courteous “yeah!” when the jumper leaps forward from the bridge and free-falls momentarily until a parachute snaps open, whipping the man’s body straight. The jumper flies down to a sandy spot on the river’s shore as a houseboat races to pick him up, the driver one of a handful of local entrepreneurs who have fashioned businesses around the rugged landscape of the canyon (the hotel Coffee or Die Magazine’s team is staying at boasts special “jumper rates” and keeps a conference room open for packing parachutes).

After watching the jumper land, Smith smiles and turns back to the dozen or so men and one woman wearing climbing harnesses who are setting up a complex system of heavy-duty ropes, extending down into the gorge. The team moves methodically and with confidence, each with a small job: running lines through hefty pulleys and brake systems, building a large tripod, keeping coiled ropes free and uncrossed. The anchor for it all is the team’s oversized Ford F-350, covered in beefy attachment points, storage bins, and stickers with the name of the team: Magic Valley Paramedics Special Operations Rescue Team.

The team is relatively small with a full membership that hovers around 16. All are full-time ambulance or flight paramedics for St. Luke’s Hospital system, which funds and manages the team.

They are all serious rescue professionals, but they are not typical ones. None are particularly active recreational climbers or mountaineers. Some grew up around mountains, but most hail from southern Idaho, a landscape that is, other than its deep river canyons, mostly flat farmland. The team raises most of its budget each year with an annual gala dinner, the Paramedic Soiree. In a good year, they’ll raise maybe $25,000.

To be sure, there are bigger and better-funded rescue teams. To pluck climbers and hunters from Alaskan mountains and glaciers, the Alaska Air National Guard has a 60-man team of pararescue specialists, supported by a fleet of kitted-out Black Hawk helicopters. In major national parks like Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and the Grand Tetons, lifelong mountaineers might put in years of visitors center duty just to get a chance to try out for backcountry positions. And the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has a corps of helicopter-borne rescue medics large enough that the service has its own Twitter feed.

Yet, call for call, man for man, the Magic Valley SORT might be the best technical rescue team in America. The team is called to dozens of rescues a year around the Snake River Canyon, nearly all of which call for quick, technical responses on jagged cliffs that vary from desert heat to ice and snow.

Somewhat uniquely, each member of Magic Valley is a working paramedic, rather than the firefighters, law enforcement officers, or other specialties. As such, the team’s DNA is built around medical care.

“Our focus is rapid access,” says Isaac Baker, another founding member of the team and the head training officer. “Getting somebody to the patient as quick as possible to start treatment, and then the rest of our team’s going to focus on getting everybody out.”

As the team set up a training scenario near the bridge last summer, BASE jumpers peeled off the center almost constantly. Yet, for all the obvious danger of the sport, the team almost never crossed paths with the jumpers.

“We’ve had two BASE jumpers over the course of the existence of this team

that actually got hung up on the bridge itself,” Smith says. One was badly

hurt, entangled in the bridge girders, and had to be lifted out with care.

The other was a woman whose chute got tangled on a beam, leaving her

swinging like a yo-yo from a few silk threads high above the canyon but

otherwise unhurt.

“We’ve had BASE jumpers that have done stunts

and end up in the boulder fields in the canyon,” Smith says. “But they’re

not that big a worry. We do one or two of those a year, but the rest are

people hiking around.”

Instead, the Magic Valley SORT stays busy with everything else around Twin Falls.

For anyone used to the sequestered landscapes of massive national or state parks — where long drives, money, and planning are needed to just reach a front gate — the right-there-ness of Twin Falls and the Snake River Canyon is hard to absorb. If you’ve ever had to reserve a backcountry campsite a year in advance, it just seems impossible that the Snake’s most awesome, sheer, and spectacular overlook is best reached by parking about 100 yards away at the Outback Steakhouse. Anybody can walk directly up to gaze at — and occasionally fall into — the Snake’s awesome depths.

As a result, the entire region is an unintentional high-angle rescue wonderland.

“Probably 90% of our rescues happen within a mile or two on either side of the bridge,” Smith says. “But then we have tons of other canyons and things that are in the area that we do a lot of rescues in as well.”

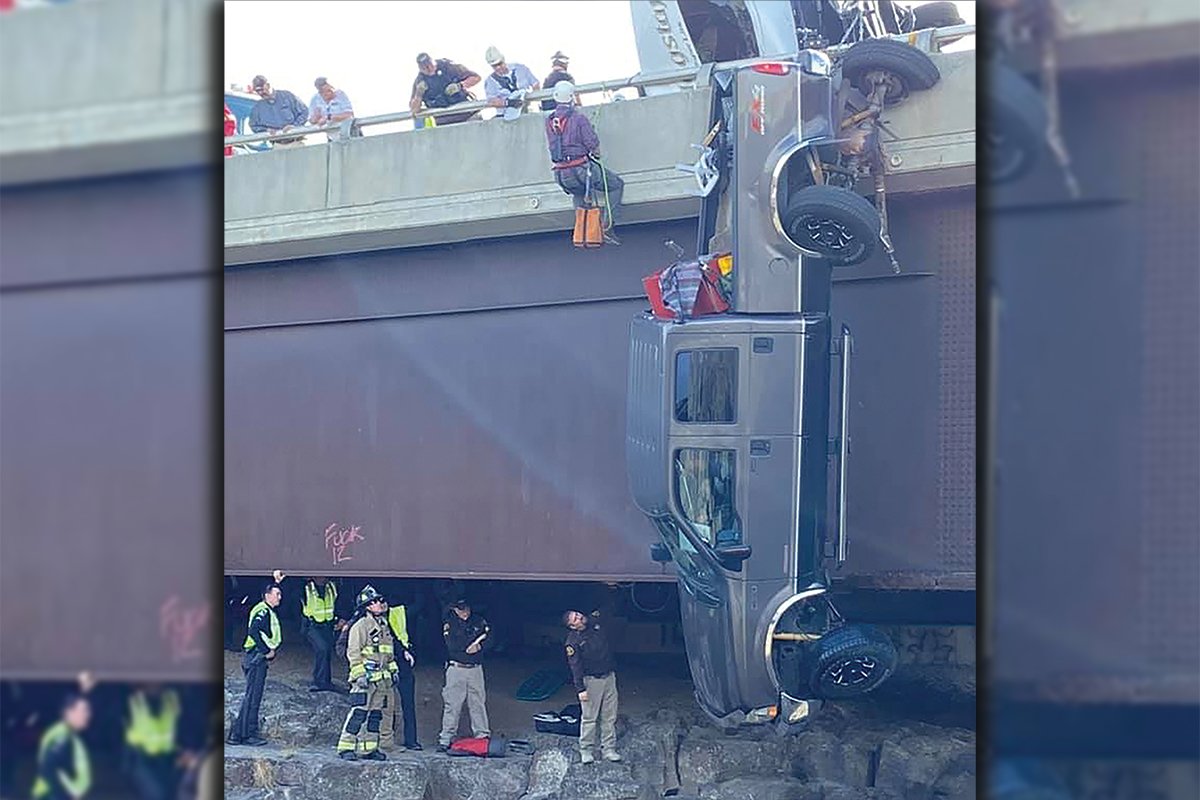

One of those calls made national headlines in early 2021 with the rescue of a couple in their 60s who were stuck dangling in their pickup, about 100 feet above a canyon known as the Malad Gorge, 35 miles outside Twin Falls. That rescue came just six months after a midwinter, nighttime deployment that required the team to rappel 300 feet down the face of a dam to reach a father and son after their truck slid off icy roads.

But even those full-throttle missions paled before the carnage the team faced with the release of a certain phone app.

“The year the Pokemon Go game came out was our busiest year for rescues in our history,” Smith says. “We did 56 rescues. I guess Pokemon like the canyon areas, and the good ones to catch were harder to get to so people that maybe didn’t have climbing or hiking backgrounds or were even in great physical shape are now hiking in the canyon in areas that you can’t get to normally. And they would fall or have medical emergencies. And then we’d have to go rescue them. We were literally doing a rescue a day for almost two months.”

Back on the canyon edge, in the span of 30 minutes, the team sends Smith and two other rescuers into the gorge on a rappel, builds a rescue-rated zip line back to the edge, and lowers a metal stretcher known as a Stokes litter to the team and their “patient.” In a few more minutes, the team packages the patient — a Coffee or Die staffer — and raises him back to the canyon edge. Since the patient can’t move during the ride, one of the rescuers even puts sunglasses on his face to fight the midday sun.

The exercise takes about an hour, Magic Valley’s self-imposed time limit for their real-world rescues.

Rescue was always Smith’s thing. He once wanted to join the Air Force for pararescue but made the mistake of revealing to his recruiter how many bones he had broken as a kid and was disqualified. Instead, he came to Twin Falls for the paramedic program at College of Southern Idaho and was quickly hired at St. Luke’s. Another St. Luke’s medic, Bill Gully, had started a team in 1996, but it had dissolved when members left.

“I was told when I got hired, hey, we have this rope rescue stuff, but we don’t really do anything with it,” Smith says.

The turning point for Smith and Gully came in 2011, when the rescue of a man who fell in the canyon took not one hour but four, with technicians and rescuers from several departments carrying different gear and having little time training together.

“It was actually Sept. 11, 2011,” Smith says. “All of the rope rescue teams in the valley had kind of dissipated. This rescue did not go smooth. So after, I started asking a lot of hard questions, along with Bill who’s kind of like the rock of our team.”

In fact, Twin Falls had several good teams. But with so many tourists, the BASE jumpers, and easy access to miles of rugged country, it was odd that the region lacked a great one. Local fire departments, county police, and the hospital’s own medics had decent gear and occasionally trained together. But when calls for help arrived, they would go out along jurisdictional lines.

Gully and Smith recruited Baker and together they hammered out a plan: They would get certified, all the way through the state’s 60-hour training programs as rescue technicians and instructors. They would set up a training schedule for members and smooth out the turf wars with local law enforcement and fire departments. The team would be open to any St. Luke’s paramedic, but only after a newbie came to training sessions for a year on their own. Once on the team, members would have to be at 80% of the twice-monthly training sessions.

And because most of the team were already fully certified flight

paramedics, they got St. Luke’s to agree to absorb the cost of using the

medical helicopters to respond to calls, making Magic Valley one of the

few nonmilitary teams in the country with air support.

By 2020,

they’d survived the Pokemon surge, and five members of the team had become

statewide instructors, helping launch other SORT teams around Idaho.

Then came six days before Christmas in 2020.

A Ford F-250, pulling a 25-foot camper, crept down a steep road cut into the wall of the canyon above the Salmon River Dam, about an hour outside Twin Falls. Chris Patterson, 58, and his son, Nathaniel, 18, were headed to a winter fishing trip that required them to drive across the top of the dam. Narrow and steep in the best of times, the road that night was covered in ice and snow. As they came down toward the final turn, from the rocky cliff to the concrete of the dam, the knobby tires on their truck began to slide toward the edge.

The truck crashed over the railing but caught a momentary reprieve. The camper caught like an anchor above, dangling the pair over the face of the dam. But soon, the truck’s frame ripped loose — the ball was still in the trailer’s hitch when police looked it over — and the cab ripped away, plummeting 300 feet down the dam’s face to a field of snow-covered rocks.

Looking back, Chris and Nathaniel probably never had a chance. The 300-foot drop was almost unsurvivable, and temperatures for anyone who did survive were below 20 degrees. Just to call 911, a witness in another car had to drive out of the canyon to get cell service. Help would have to arrive over the same icy roads.

No, given all that, Chris and Nathaniel were likely doomed.

But when the call reached the Magic Valley team, they moved like hell to get them.

Smith, by chance, was on the helicopter that night for St. Luke’s, which immediately flew to the dam, arriving overhead about 20 minutes after the call.

Orbiting above, they could see, miraculously, signs that both men had survived.

“One was trapped in the vehicle, and he was waving his arm out at us,” Smith says. “Another person was out of the vehicle shining a light at us. So we were able to relay quickly back to the team that this was actually going to be a rope rescue and not a body recovery like we thought initially.”

The helicopter dropped Smith at the top of the dam, then left to meet the SORT truck as it drove toward the site, picking up Barrett Craig and others with more gear and rushing to the scene. When the full team arrived, they quickly dropped two rappel lines over the face of the dam, sending down Smith and Craig. Smith reached Nathaniel outside the truck but found that he had died.

Inside the truck, Chris Patterson was still breathing, barely. He gasped “help me” as Smith and Craig reached him.

But the team could only access Chris through the broken driver’s window. While the team on top of the dam prepared to lower a 300-pound extraction kit, Smith and Craig started treatments with frozen hands in wet snow, leaning through the window for each procedure. They pushed two needles into the man’s chest to decompress air from a torn lung and administered whole blood through a needle shot directly into a bone in the man’s shoulder along with a clotting medicine developed for combat in the military.

As they worked, SORT’s Jerry Dillman rappelled down with extrication tools strapped inside a Stokes litter. He began tearing apart the truck around the medics.

Still, by the time they’d torn enough of the truck away to pull the man out, Patterson was unconscious and fading. The team intubated the man with a breathing tube and put chest tubes in his side. Finally, with their patient lacking a pulse as they packaged him in the Stokes litter for the trip up the dam, they started CPR.

It wasn’t enough. Chris Patterson died on the scene.

The team had not been able to save either man, but in the aftermath of the rescue, Smith saw the scope, size, remoteness, and brutal conditions of the effort as a sort of trial by fire for the team he’d been building.

“There’s nothing I would change from the night,” Smith says. (Baker disagrees: “We ran out of Copenhagen.”)

Within an hour of receiving the call, they’d delivered emergency-room-level care at the bottom of a 300-foot dam, at night, in the middle of an Idaho December snowstorm.

“I’d put my team up against any team in the nation that night.”

This article first appeared in the Winter 2022 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “Holding the Line.”

Read Next:

Matt White is a former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. He was a pararescueman in the Air Force and the Alaska Air National Guard for eight years and has more than a decade of experience in daily and magazine journalism.