5 Ways the Tet Offensive Influenced Public Perception of the Vietnam War

1968: South Vietnamese soldiers fighting in Saigon. Photo by MPI/Getty Images.

At 3 a.m. on Jan. 31, 1968, Vo Nguyen Giap, a notorious North Vietnam general, led over 70,000 North Vietnamese (NVA) and Viet Cong soldiers in a simultaneous attack against more than 100 towns, villages, and cities. His targets were American and South Vietnamese positions. Giap called for his soldiers to “Crack the sky, shake the Earth.” On the same date as the Tết Holiday — the celebration of the lunar year is the largest in the Vietnamese culture — the ceasefire was dishonored and the events that followed became infamously known as the Tet Offensive.

“Every minute, hundreds of thousands of people die on this Earth,” Giap callously said in 1969. “The life or death of a hundred, a thousand, tens of thousands of human beings, even our compatriots, means little.” His relentless fortitude and willingness to not falter from sustained setbacks had a psychological impact that shifted momentum from the general public’s view against the US military and political leadership. The Tet Offensive ultimately marked a strategic turning point in the war because although it contributed heavy losses (some 58,000 NVA and over 4,000 Americans were killed), the result further weakened the hope of ending the Vietnam War.

This list highlights the perception during the historic event that spanned several months. The perceptions that occurred in real time between the CIA and the Pentagon, photojournalists covering the surge, an insurgency comprised of women that influenced the spread of communist ideology, and much more.

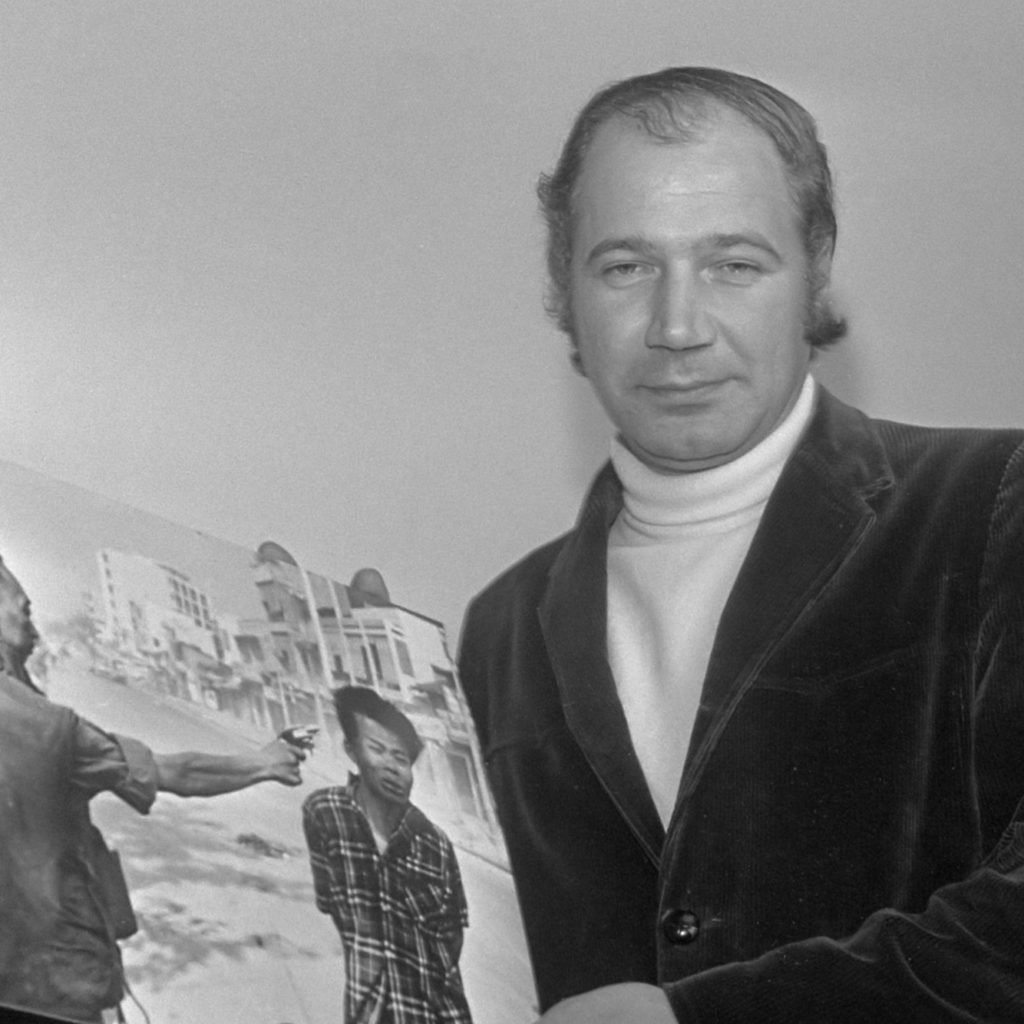

“The Marine on the Tank”

John Olson was present during the Siege of Huế, the Battle for Khe Sanh, and the battle of Saigon, the three bloodiest battles and most intense fighting during the Tet Offensive. Before he was legally old enough to drink a beer, Olson, 19, carried a camera instead of a rifle after his colleagues at UPI helped transfer him out of the US Army. He wasn’t dodging the draft — he wanted to go to Vietnam even if the Army had other ideas of stateside duty. He had previously only worked in the mailroom at UPI, so after fluffling his resume, he became the only photographer for Stars and Stripes.

“One of the wonderful things about working for Stars and Stripes, especially in my position, seeing I had nothing to wear, it meant that for all effects and purposes, with carrying cameras, you appeared to be civilian media, with far more importance than with people of my rank,” Olson later recalled during an interview with The Digital Journalist.

The Siege of Huế occurred along the Perfume River, and the only entry into the Citadel, the imperial section of the city, was from the river. Foggy and cloudy conditions limited helicopter transportation, and the destruction of a bridge erased the possibility for ground convoys, so Olson, along with a bunch of US Marines, infiltrated by landing craft. Olson spent five days embedded with the Marines as they fought house to house.

“There were tremendous casualties, and no way to treat them, no way to get them taken out,” Olson said. “There were reports and as shown in this image there [Marine on the Tank] was a Marine who was badly wounded…so badly he couldn’t be treated, and he was zipped up in a body bag while he was still alive. That’s what Hue was like.”

The joke Marines told during the battle was when they were asked how many times they were wounded, they’d quip, “Today, sir?”

Olson later worked for Life magazine, where his six-page color portfolio containing the now-famous “Marine on the Tank” photo was published. These images earned him the Robert Capa Gold Medal for documenting the experiences of American servicemen.

The Pentagon Papers

While the CIA and other intelligence services had heard rumblings of enemy activity across Vietnam leading up to Tết, they were suspicious of MACV’s (Military Assistance Command – Vietnam) reports of the “progress” they were making. The intelligence collection on the ground recognized these reports weren’t matching the realities. At the Honolulu Intelligence Conference held in January 1967, Gen. Earle Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, commented on “the contradictory order of battle and infiltration statistics which are contained in numerous documents now being circulated.”

History repeating itself with bureaucracy in the military ranks, Gen. William Westmoreland flubbed the numbers by imposing NVA and Viet Cong troop estimates had a ceiling of 300,000. Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense, had the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence deliver him a study on Aug. 26, 1966, referenced as “The Vietnamese Communists’ Will to Persist.” The North Vietnamese assessment enticed McNamara to create a small team under the Department of Defense to secretly study the US political and military involvement from World War II to Vietnam (1967). This study and the truth it revealed was leaked to the New York Times in 1971.

Select sections were published from the approximately 7,000 classified pages, which became the scandal widely known as the Pentagon Papers. The Program for the Pacification and Long Term Development of Vietnam (PROVN) suggested Westmoreland’s “body count” approach was not effective in deliberately crippling the enemy’s hearts and minds. When the Tet Offensive was initiated several months later, any notions of low enemy morale were put to rest.

Eddie Adams

It is said that the Vietnam War was “the last good war” for war correspondents because there was no censorship in the press. Words provide context to the chaos on the ground, but images from combat photographers can bring a riveting emotional reality. Eddie Adams, an Associated Press photographer, captured the intimate moment of a brutal execution of a Viet Cong soldier handcuffed in the street. Brigadier General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, the police chief of Saigon, pointed his revolver at the man’s head and fired. The photo appeared on the front page of the New York Times on Feb. 2, 1968, and its shocking violence gave Americans at home a view of the complexities and tragedy of the war.

Adams was standing next to Loan only a moment prior. “I thought he was going to threaten or terrorise the guy,” Adams recalled of the police chief’s sudden decision, “so I just naturally raised my camera and took the picture.” At the time, 72 hours into the Tet Offensive, Saigon had not yet fallen. Loan argued that violence was strength: “If you hesitate, if you didn’t do your duty, the men won’t follow you.”

The ramifications of seeing and capturing an execution and broadcasting it to the general public built doubts within Adams’ mind. He received the highest accolades, including the Pulitzer Prize. “I was getting money for showing one man killing another,” he said at an awards ceremony. “Two lives were destroyed, and I was getting paid for it. I was a hero.”

Following the war, Loan fled to the United States and opened a restaurant in Washington. When the public learned who he was, he was shamed and forced into retirement. “Two people died in that photograph,” Adams wrote after Loan succumbed to cancer in 1998. “The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera.”

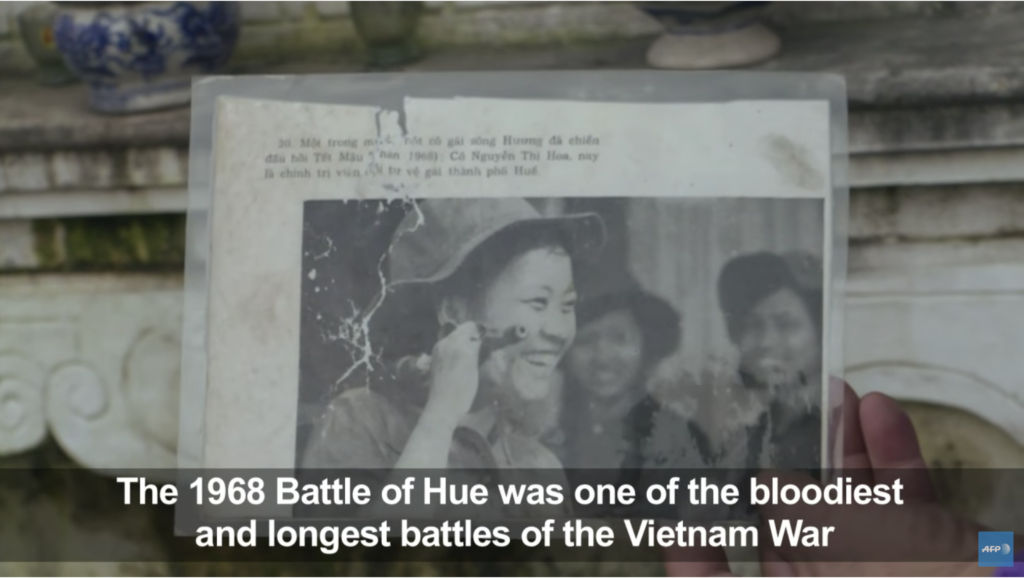

Perfume River Squad

When the battles are raging, citizens and civilians get caught in the middle. Many had to pick sides. The women behind the Perfume River Squad helped influence public opinion against the Americans and South Vietnamese. “Our duties were to enter the city to get information of movements and important locations of the enemy,” Hoangh Thi No told the Associated Press. “We also mobilized local people to support the revolutionary forces by stocking up food and digging secret trenches and tunnels, getting ready for the fight. When the offensive started, we guided our major forces to various top important locations to fight the U.S Army in Hue city.”

The goal of the Tet Offensive was to influence the South Vietnamese and their supporters against the Americans to change the tides of the war. The Perfume River Squad supported the Viet Cong, who smuggled weapons into Saigon, “even in mock funerals they had, and they got the weapons in coffins into Saigon.” During the day, the women worked their usual jobs as vendors selling conical hats in markets. At night, the women would grab handfuls of grenades and ammunition for AK-47s and dig in entrenched positions located near the stadium and behind their markets. Their bravery, at a local level, inspired other women to follow them, which backfired on the Americans attempting to demoralize their defiance.

Cao Huy Hing, director of the Revolutionary Museum in Hue, said, “The Perfume River Unit were a source of motivation for liberation soldiers and other women to join the war effort.”

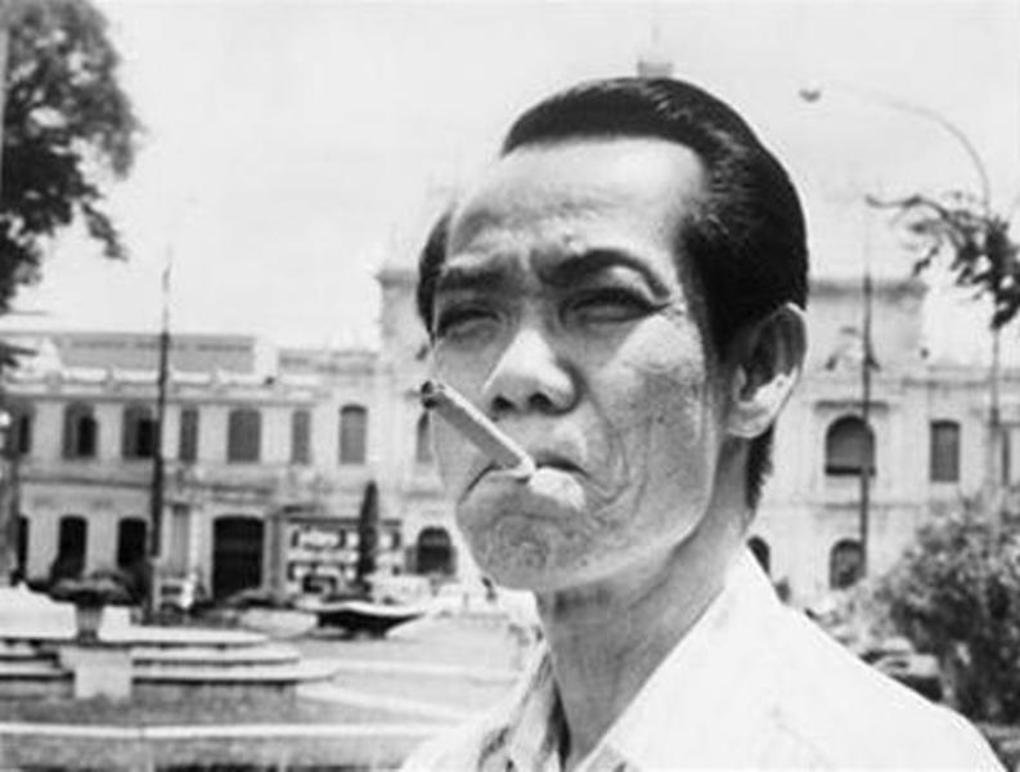

Pham Xuan An

It is often assumed that a journalist is the perfect cover for an intelligence officer. Interviewing and identifying sources, snapping pictures, traveling in and out of hostile environments, researching potential targets — all fall in line with a journalist’s typical job duties. Pham Xuan An, however, had one more layer than the other journalists and his colleagues at Time magazine. He was a double agent working against the CIA in favor of the anti-occupation allegiance of the North Vietnamese.

Stanley Cloud, Time’s Bureau Chief of Saigon, wrote fondly of An: “Although he rarely files himself, his dogged research and legwork, his remarkable knowledge and background, play an important part in virtually every file produced by a staff correspondent.”

After the French were defeated in 1954, An worked a censorship role in a post office. His mentors — William Colby, a former director of the CIA, and Colonel Ed Landsale, a sadistic CIA advisor in Vietnam known for his “Eye of God” psychological warfare religious campaigns — molded An’s impressionable attributes. He later spent two years studying journalism at a junior college in the US. His first byline was in The Barnacle, his school’s newspaper. The Asia Foundation filled his pockets with a completely funded tuition. The CIA connection didn’t waver because The Asia Foundation was a front to shield covert action programs in Asia.

His work for Reuters and Time gave him credibility and earned him honest praise. “Two things impressed me about An. He understood American journalism, and he was highly intelligent,” said Frank McCullock, the managing editor for the LA Times, in a 2006 interview. “Because he was so well connected, he knew Vietnamese politics intimately, and in 1964 when I first arrived in Vietnam politics, unfortunately, was a bigger story than the war itself. The coups d’etat came and went so fast that if you were going to cover Vietnam you had to have Vietnamese know-how, and that’s what An provided.”

An worked in the bureau of the Time-Life office in Saigon and was exposed to every source of information the reporters collected. McCullock even stated how An had a scoop from a source in the military of exact American troop estimations and deployment schedules three months before the US prepared to send 545,000 troops to South Vietnam. An filed the story; however, it was ultimately killed because President Lyndon Johnson lied about his real intentions to the fact checker. He was the source of several other reporters’ stories because of his access.

While other reporters spent their evenings drinking beer, An transformed his home into a den of espionage after his family went to bed. His superiors from Vietnamese intelligence services in Hanoi delivered him intelligence cables and photographs. In the morning, before the bustle at the bureau, he walked his German shepherd at a horse racing track. The film canisters he developed the night before and messages written in invisible ink were hidden in ninh hoa, a Vietnamese egg roll. He discreetly delivered to a dead drop disguised as a bird’s nest in a tree. He even went so far as to hide secret material under a gravestone, intended for one of the many men and women couriers he used as assets.

His reports went all the way up the NVA chain of command to reach Gen. Giap. “We are now in the U.S. war room,” he joked. When An worked for the newspapers, he alleged that he didn’t try to influence or provide an angle in support of the North Vietnamese. “It would have been stupid to do that. He would have been found out in an instant,” said McCullock.

An was a complicated person acting on his own behalf with the integrity instilled from his past mentors. “He didn’t believe we belonged in his country. He was a nationalist,” author Lee Berman said. “He felt this is something the Vietnamese had to settle between themselves.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.