The Crag Rats: How a Band of Outdoor Hobbyists Transformed Mountain Rescue in the Pacific Northwest

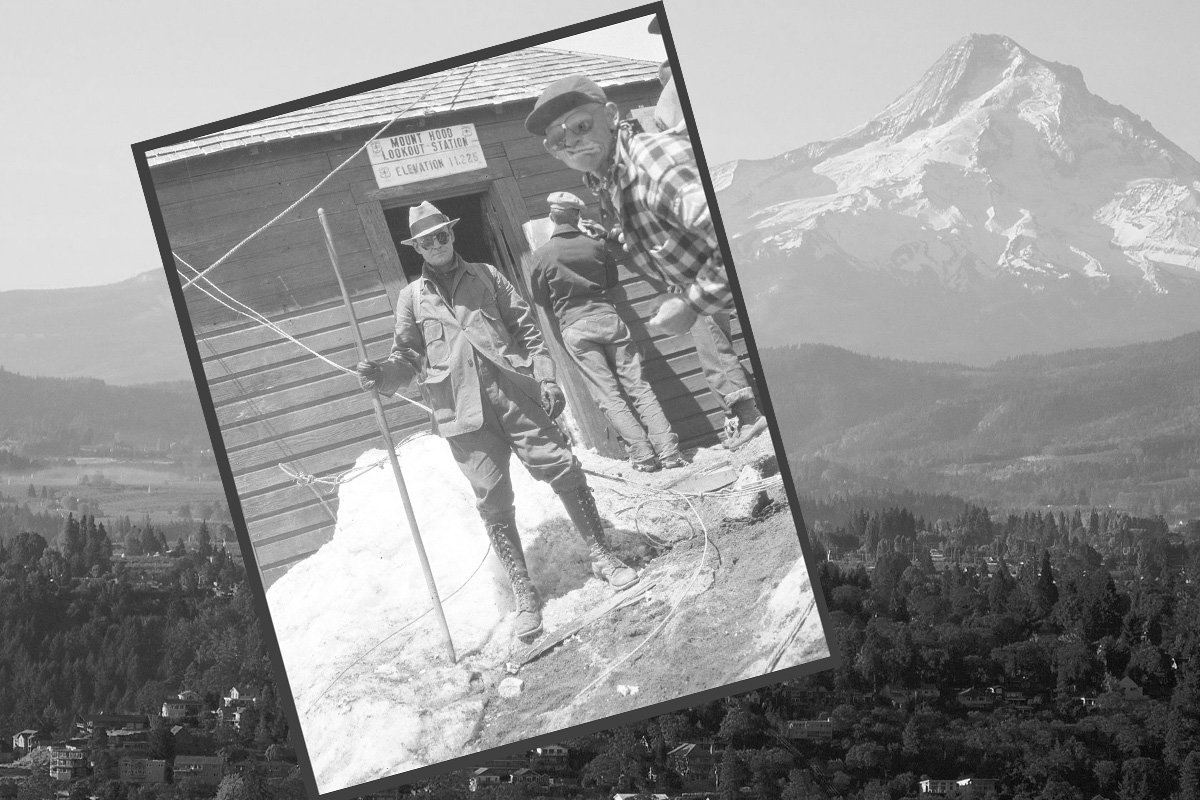

The Hood River Crag Rats pioneered mountain rescue in the Pacific Northwest in the 1920s and have remained active ever since. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

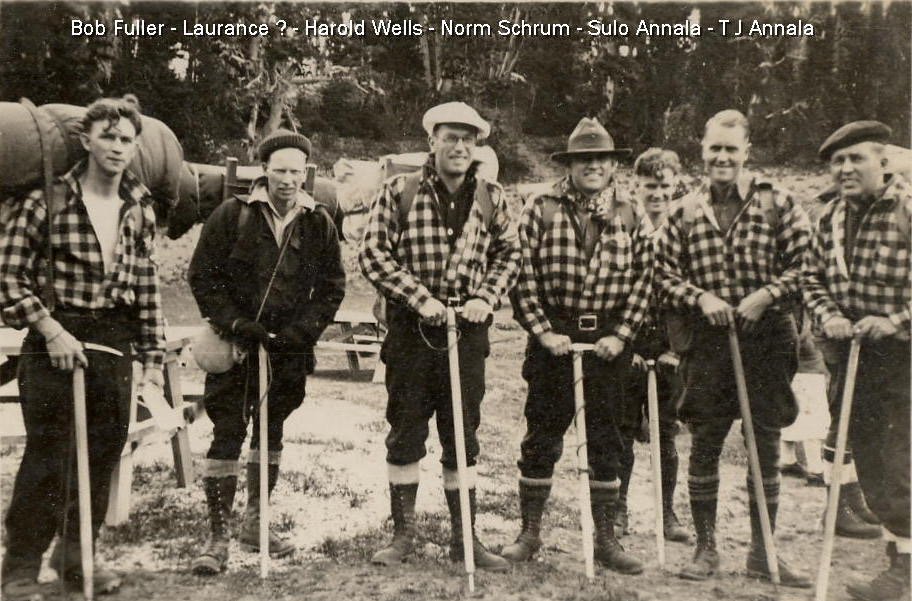

In the summer of 1926, lumberman Andy Anderson held a landmark meeting at his home in Hood River, Oregon. In attendance were experienced climbers and ski mountaineers, many of whom had previously belonged to Company 12 of the Oregon National Guard Coast Artillery unit.

At that time, people were going missing in the area’s mountains at an alarming rate. These grizzled mountain folk wanted to do something about it.

The first real test came about 10 days after the group’s debut meeting, when a local sheriff’s department deputy called the team and asked for its help in the search for a missing 7-year-old boy named Jackie Strong. The boy’s two brothers had left him alone in their forest camp to go fishing. When the mother called the boys for dinner, Jackie never showed up.

Anderson assembled his team, and they trekked through the glacier-clad Mount Hood area in search of the boy. For three days, some 250 volunteers scraped through the area until Jackie was discovered on a rock in the remote headwaters of Lost Creek.

A curious reporter asked about the rescuers’ identities. On the spot, the men thought of the name given the team at a meeting held at the group’s hut, or clubhouse. There, Anderson’s wife, Delia, had concluded that two words would suffice — “Crag Rats.”

“You’re in the crags of the mountain, looking for people,” she had said, according to the recollections of Bill Pattison, 93, the Crag Rats resident historian who’s been a member of the group since just after World War II. “And you’re just a bunch of rats because you’ve deserted your families on the weekends.”

The colorful name caught on in the newspapers even before the Crag Rats officially formed as the nation’s first mountain search and rescue team. It wasn’t long before they were called upon again. In January 1927, a 16-year-old named Calvin White Jr. disappeared while skiing. Crag Rat Bill Cochran found White after three days of exhaustive searches and brought him back down to safety. Although he lost some toes to frostbite, White survived.

On average, the Crag Rats performed six major rescues per year thereafter and frequently captured newspaper headlines for their daring exploits, which they pulled off with nothing more than their personal mountaineering equipment.

“The communications were: Everybody carried a gun, and you fired off a different number of rounds,” Pattison told Coffee or Die Magazine in an interview. The gunshots were a coded system — two shots meant the rescuers had located a body, and three shots signaled a request for help.

“And then, later on, they had whistles for closer communication. No radios,” Pattison said.

By 1931, the Crag Rats had solidified their place in local lore.

“The monks who have kept the hospice on the St. Bernard Pass in the Swiss Alps for more than eight centuries have won enduring fame, but few persons outside the Pacific Northwest have heard of the Crag Rats of Hood River, Ore.,” a Philadelphia-based newspaper declared in 1931. “They might be called the St. Bernard monks of this country.”

In those pre-World War II days, only about 3,000 to 4,000 residents in the Mount Hood area were participating in recreational activities — a far cry from the roughly 50,000 residents who populate the region today.

“The Crag Rats were very restricted to only residents of Hood River County,” Pattison said, adding that there were no women in the Crag Rats’ ranks until rather recently. “And the neighboring counties really didn’t have the physical terrain to get lost on. How do you get lost in a wheat field, as opposed to Mount Hood?”

The Crag Rats conducted rescues with the limited gear they had on hand. Innovative changes didn’t materialize until soldiers who’d fought battles in the Italian Alps returned home from World War II.

“The establishment of the 10th Mountain Division organized search and rescue techniques, equipment, training, and ways of doing things that spurred an increase of recreational use in areas like national parks and national forests,” Pattison said. “The Crag Rats just went along with what was going on at the time, and our training came out of the 10th, from rope work to training manuals.”

In 1959, the Mountain Rescue Association was founded. The new organization provided a clearinghouse for other mountain rescue teams situated around the country and — ultimately — around the world.

“They set it up essentially to be an organization that would accredit teams in three specific disciplines: in rigging, snow and ice, and search theory,” Mountain Rescue Association president Doug McCall told Coffee or Die. “And the Mountain Rescue Association has developed now into about 90-plus teams, with about 3,000 volunteers nationwide.”

Although technology has reinvented the rescue industry, the techniques first adopted by the Crag Rats remain relevant and continue to save lives.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2022 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “The Crag Rats.”

Read Next: Holding the Line: America’s Best Technical Rescue Team Is in Small-Town Idaho

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.