‘The Town That Didn’t Stare’: How the Guinea Pig Club Assimilated Into the Community

The Guinea Pig Club was the most exclusive club of World War II that nobody wanted to be a part of. Composite made by Kenna Milaski/Coffee or Die Magazine.

It was a club no one wanted to be a part of. The members were teenagers and young men who had believed they would escape World War II unscathed. Once in the club, they found it was “the most exclusive club in the world, but the entrance fee is something most men would not care to pay and the conditions of membership are arduous in the extreme,” as Sir Archibald McIndoe wrote.

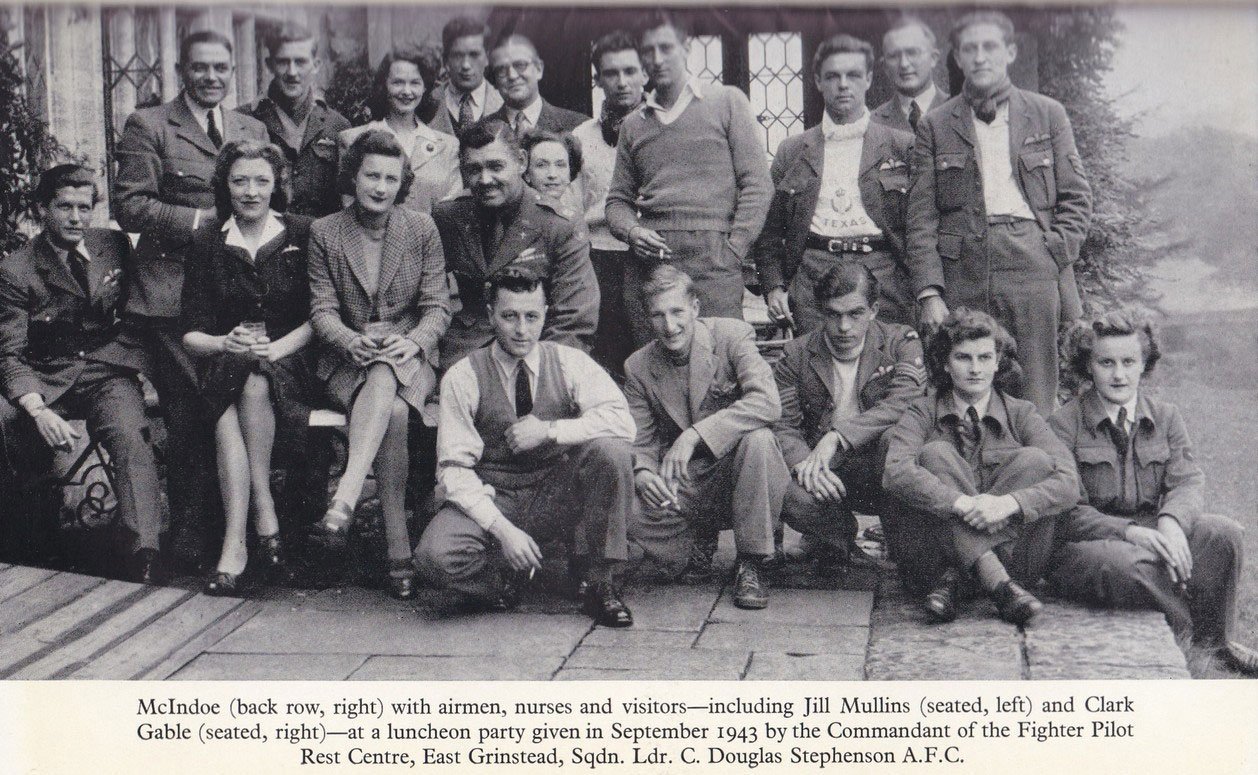

Over the course of World War II, 649 Allied airmen found themselves members of the Guinea Pig Club, the group name adopted by the patients of New Zealand plastic surgeon McIndoe, who developed pioneering medical treatments and social rehabilitation strategies for burned service members. His patients often said they were “just a guinea pig for the Maestro.”

Club members included Allied aircrew who had had two medical operations on burns and other crash injuries, which were often on hands and faces, at Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, about 25 miles south of London. One of these patients was Royal Air Force pilot Geoffrey Page, who helped found the club.

On Aug. 12, 1940, during the Battle of Britain, Page was shot down over the English Channel. “Surprise quickly changed to fear, and as the instinct of self-preservation began to take over, the gas tank behind the engine blew up, and my cockpit became an inferno,” Page recalled in his book Shot Down in Flames. “Fear became blind terror, then agonized horror as the bare skin of my hands gripping the throttle and control column shriveled up like burnt parchment under the intensity of the blast furnace temperature. Screaming at the top of my voice. I threw my head back to keep it away from the searing flames.”

Page bailed from his burning Hurricane aircraft, pulling the rip cord on his parachute. Later, as he was first being treated for his injuries, Page caught sight of the swollen and burnt flesh that had once been his face, and he realized his attempts to protect it from the flames had failed.

Before Page had gone to war, he’d had no concept of its true destructive power. “Paradoxically, death and injury had no part in it. In the innocence of youth, I had not yet seen the other side of the coin, with its images of hideous violence, fear, pain and death.”

Page dedicated his book to McIndoe, “whose surgeon’s fingers gave me back my pilot’s hands.”

Page wasn’t alone in his debt to McIndoe.

McIndoe led the charge in developing medical treatments for burn victims. He championed the banning of tannic acid, then the universal treatment for burn victims, because it caused the skin to contract, making reconstructive surgery less successful. Tannic acid prevented fluid loss and infection by creating a hard protective shell over wounds, but the process of removing the shell before a patient’s reconstructive surgery was incredibly painful. Instead, McIndoe introduced saline treatments and basic first-aid procedures. He also implemented the tube-pedicle technique, which proved to be more effective than previous skin-grafting methods for facial and hand reconstruction.

In the early days of McIndoe’s treatment facility, he had three separate patient wards. Ward I was for dental and jaw injuries. Ward II was for women and children. Ward III was for officers and victims with the most severe burns and injuries.

McIndoe also introduced revolutionary social rehabilitation strategies for his patients. He requested Ward III be painted with cheerful colors to remove the hospital-like appearance. He put a piano in the ward to encourage singing among the airmen and even provided a barrel of beer to promote social gatherings and conversations. McIndoe deemed practical jokes and flirting with the nurses acceptable because he believed restoring confidence was essential for his patients’ future relationships in society.

McIndoe even went as far as stripping his patients of their “hospital blues” — special uniforms — because he felt it made them look like criminals and feel sorry for themselves. He championed his patients and informed the citizens within the town of East Grinstead to do the same. East Grinstead has since been remembered as “The Town That Didn’t Stare.” Patients could enjoy drinks at the Whitehall restaurant, which became the unofficial social club for them. McIndoe got celebrities, newspapers, and the Guinea Pig Club members to invite patients to theater and film premieres.

Although the Guinea Pig Club was disbanded following World War II, the former members gathered annually until 2007.

Read Next: 4 Unusual Weapons From the Civil War

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.