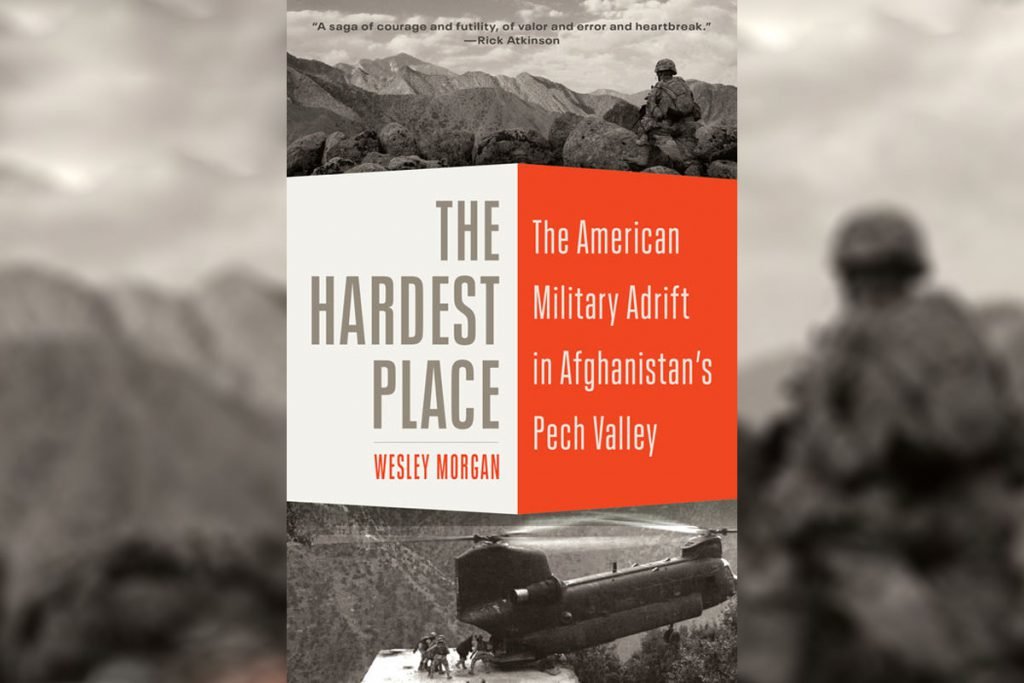

Review: ‘The Hardest Place’ Is a Definitive Account of War in Afghanistan’s Pech River Valley

Afghan soldiers man an observation post in the Pech Valley in 2013. Photo by Wesley Morgan.

In America’s longest war to date, few places have proved more volatile, costly, and confusing than the Pech. The Pech River Valley sits in the rocky northeastern corner of Afghanistan, in the provinces of Kunar and Nuristan. With notable branches like the Korengal and Waygal, the Pech is composed of some of the most austere terrain in the world. The valley is a patch of Afghanistan marred by heavily forested mountains with 10,000-foot snowcapped peaks, Alpine cliffs, and boulder-strewn valley floors. If it weren’t for its legacy of death, the Pech would be renowned for its natural beauty.

It’s here, among the forests and mountains, that America became most mired during its 20 years of war in Afghanistan. It is impossible to understand the war without first understanding the fight for the Pech, a fight with abstract goals and ever-shifting metrics for success. Despite being the site of 13 Medal of Honor actions and holding a large share of the 2,354 Americans killed in Afghanistan, America’s mission in the mountains has remained consistently cloudy.

After more than a decade of research, multiple trips to the region, and exhaustive interviews, Wesley Morgan has completed the definitive account of war in the Pech. The Hardest Place demands a spot on every bookshelf of those who seek to better understand America’s longest war. Packed with details, the book leaves no stone in the valley unturned, yet never releases the reader’s attention. In the same vein as Sebastian Junger and Jon Krakauer (both acclaimed journalists with their own riveting accounts of war in Afghanistan), Morgan demonstrates an expert ability to combine hard-researched journalism with unrelenting narrative. The Hardest Place contains more information than a textbook yet remains as pleasurable to read as a novel. Through intelligence dockets, interviews with veterans of both sides, and after-action reports, Morgan weaves an incredible story of combat, heroism, and tragedy, beginning with the first Americans to arrive in the valley.

Following the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, US intelligence tracked Usama bin Laden to Tora Bora in the neighboring White Mountains. There, a battle ensued that toppled the Taliban government but failed to kill the al Qaeda leader. Following bin Laden’s evasion, the US sought to track down everyone associated with al Qaeda by detaining all foreign Arab fighters in the region. Intelligence gathered from al Qaeda prisoners pointed toward the Pech and its tributaries as a potential enemy stronghold.

In the 1980s, during the Soviet war in Afghanistan, it was among the mountains that the mujahedeen found success against more powerful Soviet forces. The caves and heavily forested ridges gave the poorly equipped Afghan fighters a tactical advantage, so it came as no surprise that America’s enemies sought refuge in the same location. In response, the United States deployed groups of special operators from Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) into the valleys to seek out key enemy leaders. These small groups of American operators established the first permanent US base in the Pech, marking the first step in a long march to nowhere.

Soon after JSOC’s arrival, the small group of SEALs and Green Berets were augmented by some 100 operators of the Army’s elite 75th Ranger Regiment, which Morgan describes as “JSOC’s brawn,” marking a clear shift in strategy. As Ron Fry, a Green Beret who deployed to the Pech early on with Operational Detachment Alpha 936, later explained, “Rangers are constantly trying to squash cockroaches. We’re trying to make the building uninhabitable for cockroaches.” Fry’s ODA 936 was soon replaced by another ODA with an aggressive approach more in line with the Rangers. Unlike Fry’s decision “not to go kick a hornet’s nest,” the newly deployed ODA 361 was supported by a company of Marines from 3/6, and together they followed the Rangers’ lead and pushed aggressively into one of the more volatile offshoots of the Pech: the Korengal.

The story of combat in the Pech is one of escalation. As more Americans operated in the valley, more attacks ensued, resulting in even more Americans being deployed into the mountains. Morgan describes the escalation as “a self-licking ice cream cone.” In 2004, two large attacks on American positions resulted in an even greater troop surge. The few operators of ODA 361 were replaced by an entire Marine infantry battalion. Soon after the Marines took over responsibility, America suffered one of its most crushing military losses.

By 2005, the Marines had begun incurring casualties due to an increase in improvised explosive devices and small arms attacks. In an effort to aid the Marines, a group of SEALs offered to help coordinate a large operation deep into the Korengal, in what became known as Operation Red Wings. It was during the day prior that a team of four SEALs became compromised, kicking off the costliest fight of the war up to that point. After three of the four SEALs were killed, a Quick Reaction Force of eight SEALs and eight Army Special Operations Aviators responded. Upon insertion, their helicopter was shot down, killing all on board. Prior to the operation, 69 Americans had been killed in Afghanistan, a relatively low number compared with the concurrent war in Iraq. Morgan explains, the deaths of 19 special operators raised the death toll by more than a quarter in a single afternoon — “a shock to a country and military that had mostly written Afghanistan off as a war already won.” Weeks later, the Marines launched Operation Whaler in retaliation, resulting in an estimated 150 enemies killed at the cost of one dead Marine.

Similar to the escalating effect 2005’s Operation Red Wings had on the Korengal, 2003’s Operation Winter Strike had a similar negative effect on Waygal: another of the Pech’s branches. That operation had been less costly for Americans, but an airstrike reportedly killed several civilians and in turn drove the Waygalis to view Americans as their enemy. In such a remote corner of Afghanistan, the US military found itself waging separate wars against the foreign Arab fighters of al Qaeda, Taliban soldiers, and local tribes such as the Waygali and Korengali, though many Americans never made the distinction. When attacks seemed to come from ghosts high in the snowy peaks, it made little difference to those on the receiving end who was squeezing the trigger. American and Afghan escalation continued. In the Waygal specifically, a growing insurgency was met with force: in the form of the Army’s 10th Mountain Division.

Read Next: Operation Red Wings Through the Eyes of the Night Stalkers

By 2006, 700 soldiers of the revered unit replaced all remaining Green Berets and Marines in the region. These soldiers of the regular Army bore the brunt of the fighting in the Pech. In The Hardest Place, Morgan not only chronicles the intense combat that followed but also attempts to understand why the battle space was so fervently contended by the enemy. In addition to the advantages steep mountainsides and low valleys provided, the natural resources there were a source of funding that neither the Taliban, nor their tribal allies, could relinquish. Like the lucrative opium flowing out of southern Afghanistan’s poppy fields, the rich timber and minerals coming from the north proved too profitable to abandon. When Afghan President Hamid Karzai declared logging illegal, the price of quality timber only went up, bolstering the enemies’ zeal for defending it.

Morgan rivals the best war storytellers in his descriptions of combat. He describes infamous battles in the Pech, such as the Ganjgal, Rock Avalanche, The Ranch House, Kamdesh, and Wanat, with such skill that he nearly transplants the reader there. These engagements were fought with such ferocity that they read as if they were of a different era. In modern battle spaces dominated by unmanned aircraft, laser-guided bombs, and up-armored vehicles, it is shocking to read Morgan’s descriptions of combat taking place at ranges closer than 30 meters.

During Operation Rock Avalanche, for example, enemy fighters were close enough to strip a dead American of his weapon and attempt to drag away another wounded soldier. During the battle of The Ranch House, one soldier found himself confused when his 40 mm grenades weren’t exploding. Only later did he make the shocking realization that the enemy he had been firing at was within the 46-foot arming distance of his grenades. The battles that unfolded around the Pech were some of the most chaotic engagements Americans had been in since the Vietnam War, and few have described them in such harrowing detail as Morgan.

As US involvement in the region grew over time, so did the body counts of both enemy and American troops. And while strategies differed among Green Berets, Rangers, SEALs, Marines, and soldiers, so changed who they were fighting, from al Qaeda and the Taliban, to tribesmen defending single valleys. By 2015, the war had evolved into a fight, not only against these enemies, but also against ISIS, or Daesh. The rapid rise of the Islamic State only further clouded the already murky water of Afghanistan. Daesh proved to be a shared enemy among coalition forces, local tribes, and the Taliban, causing an unintended, if not taboo, alliance. Morgan explains the new role of Americans in the fight against ISIS:

When the [Afghan National Army] went up a valley, […] Reapers roamed above, watching for Daesh movements. […] The advisers would watch the drone feed and pass along coordinates for strikes to the artillerymen and sometimes to fighter jets and Apaches, pummeling Daesh observation posts and reinforcements when they moved forward to lay ambushes for the ANA. The sound of the artillery pounding targets beyond the next ridgeline heartened the Afghan troops on the ground. […] The ANA didn’t say so explicitly to the American advisers, because they knew the U.S. still viewed the Taliban as a hostile force, but it seemed clear that they were using local Taliban as guides and auxiliaries.

One former Delta Force operator who fought in the Pech simplified most Americans’ view of the shifting enemy: “Same drunks, same bar.” To those who fought and bled in the unforgiving topography of northeastern Afghanistan, who the enemy fighters swore allegiance to mattered little. The bottom line was they were killing Americans. Another veteran of the Pech developed his own rationale for the sacrifices he and his men made there. To him, it was about keeping the fight contained overseas. When people would thank him for his service and express guilt for not having involved themselves personally, he would answer, “That’s why I’m over there. That’s why I’m fighting the away game.”

Morgan does not directly lay out an answer as to whether or not America’s struggle in the Pech was worth the cost, or even why the military became so committed to a remote piece of geography. Rather, he highlights the complexity of US involvement while preserving the heroism of the men and women who fought and died there. The narrow view of America’s mountain war that readers are accustomed to, as described in great books such as War, Into the Fire, The Outpost, Lone Survivor, and Alone at Dawn are now enhanced by Morgan’s ability to examine the larger ramifications in The Hardest Place.

Morgan’s unique ability to weave an incredible story of American heroism and sacrifice with the hard-to-swallow truths surrounding the Pech serve as a microcosm of the entire Afghan war. When future generations reflect on America’s longest war and those who fought it, The Hardest Place should be the first book they reach for.

The Hardest Place: The American Military Adrift in Afghanistan’s Pech Valley by Wesley Morgan, Random House, 672 pages, $35

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.