The Mitrokhin Archive: Soviet Defector Reveals Historic Large-Scale Subversive Operations Against the West

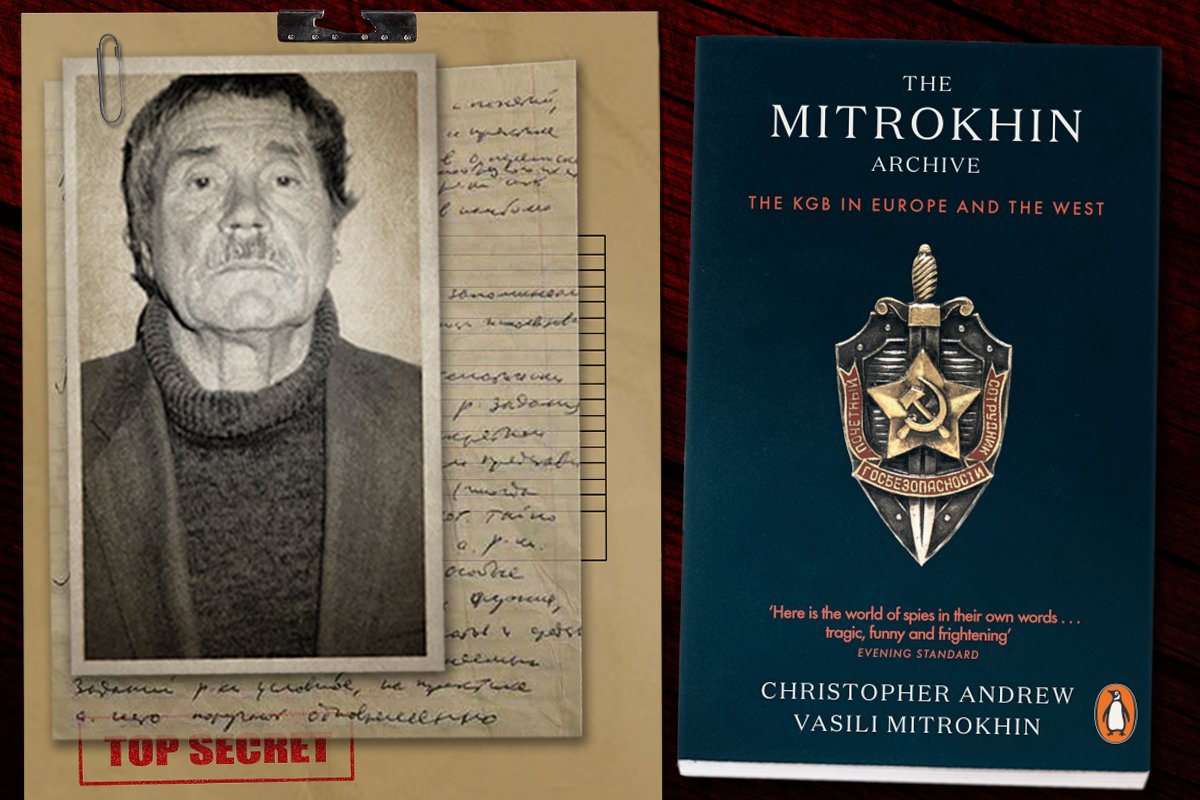

In 1992, KGB archivist and Soviet Union foreign intelligence officer Vasili Mitrokhin defected to the West. He smuggled out notes so detailed that the FBI said the information was “the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source.” This material became known as the “Mitrokhin Archive.” Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

In December 1996, a German magazine called Focus reported that a KGB officer had defected to Britain with the names of hundreds of Russian spies. Tatyana Samolis, the spokeswoman for the SVR — Russia’s post-Soviet Foreign Intelligence Service — immediately ridiculed the story as “absolute nonsense.”

“Hundreds of people!” she exclaimed. “That just doesn’t happen! Any defector could get the name of one, two, perhaps three agents — but not hundreds!”

The story was far more explosive than anyone had first perceived, and its ripple effects exposed not hundreds but thousands of Russian agents and foreign intelligence officers all across the globe, including so-called illegals living in deep cover abroad while disguised as foreign citizens.

The secret files compiled by career Soviet foreign intelligence officer and KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin became known as the “Mitrokhin Archive.”

Vasili Mitrokhin’s Defection

Mitrokhin’s career began in 1948, but after he spent decades observing injustices within the Soviet system, his outspokenness got him pulled from fieldwork and relegated to desk duty at KGB headquarters. In June 1972, Mitrokhin became responsible for checking and sealing 300,000 KGB files at the First Chief Directorate (FCD) — the KGB’s foreign intelligence arm — during its move between offices in Lubyanka to a new building in Moscow’s Yasenevo District.

For 12 years, Mitrokhin scribbled handwritten notes about more than seven decades of both pre-Soviet intelligence activity and KGB activity in the Soviet Union, Europe, Afghanistan, and the United States. He stashed these notes in his shoes and inside milk containers hidden underneath the floorboards of his log cabin or buried in his garden. Shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Mitrokhin boarded an outbound train from Moscow to the newly independent Baltic republic of Latvia to defect to the West.

“When the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) exfiltrated the defector and his family from Russia in 1992, it also brought out six cases containing the copious notes he had taken almost daily for twelve years, before his retirement in 1984, on top-secret KGB files going as far back as 1918,” Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin write in their book The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. “The contents of the cases have since been described by the American FBI as ‘the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source.'”

Mitrokhin’s defection was kept secret until 1999, when his book was published and then serialized on the front page of The Times of London. Among the first dominoes to fall in the exposé was the unmasking of Melita Norwood, an 87-year-old great-grandmother whom The Times described as “the spy who came in from the co-op.” Norwood spied for the KGB against Britain for some 40 years and was the longest-serving of all Soviet spies in Britain.

After debriefings from the British Secret Intelligence Service — known more commonly as MI6 and the United Kingdom’s equivalent to the CIA — the West learned of shocking espionage activities, subversion campaigns, and large-scale sabotage operations Soviet intelligence and the KGB had carried out since the 1920s.

The Great Illegals Program in the West

The Soviets honed their patient approach to espionage in the early to mid-1930s. The celebrated era of those known in Soviet intelligence circles as the “Great Illegals” saw the predecessor of the KGB send deep-cover officers to infiltrate European nations’ governments and spy agencies. Soviet agents targeted young, sympathetic men drawn to communism, which ultimately led to the formation of the notorious spy ring often referred to as the “Magnificent Five” or, in the West, the “Cambridge Five.”

Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, and a fifth spy believed to be John Cairncross were recruited while they attended the University of Cambridge. They passed government secrets from the Foreign Office, MI5, and MI6 throughout World War II until at least the 1950s. Philby was even appointed the head of MI6’s anti-Soviet section while working as a double agent for the KGB.

The Great Illegals set the framework for other deep-cover assignments in the West during the Cold War. The case involving the couple Karl and Hana Koecher reveals how seriously the Russians took espionage assignments to infiltrate Western intelligence agencies.

The Koecher couple developed a “legend,” or cover story, depicting a phony defection in 1965 from Czechoslovakia to shield their spy activities in Washington, DC, and New York. Karl Koecher obtained jobs as a CIA translator and analyst working between 1973 and 1978.

“Karl Koecher seems to have been the first illegal to find employment for the CIA,” Andrew and Mitrokhin write. “The Koechers were habitués of Washington and New York sex clubs where they had sex with personnel from the CIA, Pentagon and other parts from the federal government.”

Karl Koecher met with Czech and KGB handlers at safe houses in Austria and Switzerland to pass classified documents until the FBI arrested him after 20 years of spying.

The successes of the Great Illegals program have continued into at least the 2010s, evidenced by the FBI’s Operation Ghost Stories, which led to the arrest of 10 sleeper agents belonging to Russia’s SVR.

Active Measures Against the US

Active measures are operations aimed against the “Main Adversary” — a term the Russians assigned to the West — to weaken the resolve of the American people and their trust in their own government amid tumultuous moments in US history. Several conspiracy theories still whispered about today have their origins in KGB rumors, including claims that the CIA was involved in the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1971, Anatoli Tikhonovich Kireyev, the head of the FCD’s North America Department, launched Operation Pandora to create a racial divide in New York. Operation Pandora involved placing a delayed-action explosive package in “the Negro section of New York.”

“After the explosion the residency was ordered to make anonymous telephone calls to two or three black organizations, claiming that the explosion was the work of the Jewish Defense League,” Andrew and Mitrokhin write. The bombing was never carried out and Moscow failed to propel the US into a race war.

One of the more successful anti-American active measures was a false story “that the AIDS virus had been ‘manufactured’ by American biological warfare specialists at Fort Detrick, Maryland,” Andrew and Mitrokhin write.

Code-named Operation Infektion, the KGB plot successfully weaponized fake news to create distrust in the US government and the media. In the late 1980s, an age without the Internet, this plot spread through international newspapers, TV broadcasts, and even word of mouth in 80 countries. In the 21st century, weaponizing the news has become far easier for intelligence agencies through the exploitation of social media.

Potential War With NATO — Large-Scale Sabotage Operations

The KGB planned a massive campaign of sabotage and disruption in North America behind enemy lines in case NATO went to war with the Soviet Union during the 1960s. The critical pathways to target infrastructure exploited the weaknesses across the US-Canada and US-Mexico borders.

The KGB set up splinter groups of Nicaraguan Sandinista guerrillas along the US-Mexico border with support bases in the areas of Ciudad Juarez, Tijuana, and Ensenada. To fulfill the KGB’s sabotage and intelligence goals, the DRG (Soviet sabotage and intelligence groups) leader, Manuel Ramón de Jesús Andara y Úbeda (code-named Prim), traveled to Moscow to undergo training.

“Among the chief sabotage targets across the US border were military bases, missile sites, radar installations and the oil pipeline (codenamed START) which ran from El Paso in Texas to Costa Mesa, California,” Andrew and Mitrokhin write. “Three sites on the American coast were selected for DRG landings, together with large-capacity dead drops in which to store mines, explosive, detonators, and other sabotage materials.”

A support group code-named Saturn was tasked with using migrant workers to conceal movements of agents and weapons across the border. Saturn’s headquarters was a hotel owned by a Russian-born agent code-named Vladelet in Baja, California, some 50 miles away from the border. The agent’s two sons operated a gas station to hide weapons and sabotage materials for future operations against the United States.

The DRG and KGB also believed Canada served as a viable border crossing to strike US targets, including a dam on Montana’s Flathead River that the KGB believed generated “the largest power supply in the world,” Andrew and Mitrokhin write.

KGB and DRG saboteurs planned to conduct simultaneous attacks against the dam in Flathead — now officially known as the Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ Dam — and the nearby Hungry Horse Dam to sabotage their sluices.

“The state with the largest number of targets, however, was almost certainly New York, where DRGs based along the Delaware River, in the Big Spring Park near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and at other locations planned to disrupt the power supply of the entire state before taking refuge in the Appalachian Mountains,” Andrew and Mitrokhin write. “As well as being a base for KGB ‘special tasks’ against the United States, Canada was also an important target in its own right. Operation KEDR (‘Cedar’), begun by the Ottawa residency in 1959, took twelve years to complete an immensely detailed reconnaissance of oil refineries and oil and gas pipelines across Canada from British Columbia to Montreal.”

The concerning evidence exposed by the Mitrokhin Archive reveals the Soviet Union — and now Russia — had far more sabotage operations planned against the United States than the US had realized. Mitrokhin, who died in 2004 at the age of 81, “was a hero,” according to his co-author Andrew.

“Every day of his life for 12 years, he did something without any prospect of personal gain, because he believed in it,” Andrew said in a 1999 60 Minutes interview. “And if he had been found out on any of those days, he’d have been executed. It was as simple as that.”

Read Next: DISPATCH: How One Ukrainian City Is Preparing To Resist the Russians’ Arrival

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.