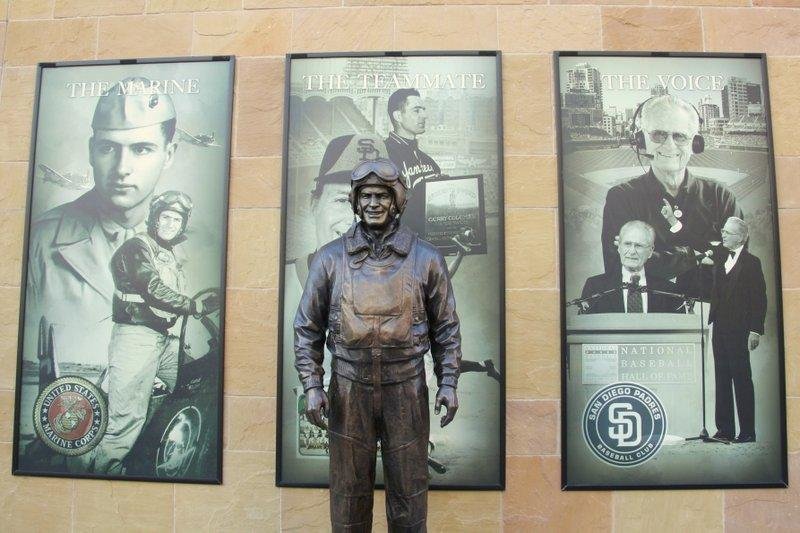

Jerry Coleman was the only Major League Baseball player to see combat in both World War II and the Korean War. Photo courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The night was black with no moon to illuminate the sky. A sortie of F4U Corsair bombers piloted effortlessly by U.S. Marine Corps aviators flew through the air on a mission into North Korea, one that carried much risk because they were not supposed to be there.

Captain Jerry Coleman led the formation but realized something had gone horribly wrong shortly after takeoff. He could not see anything in front of him — it was abnormally dark, like a shade had been drept over his windshield. Determined to fix the problem without breaking radio silence, Coleman grabbed the top of his cockpit door, slipped it open, and peeked his head outside to see what was obscuring his view. A stream of black oil splashed across his face, and the wind ripped his communications equipment from his head and to the ground below.

Coleman had a decision to make: abort the mission and return to base alone, leaving his wingmen exposed, or continue with the mission flying blind. It wasn’t a difficult decision — Coleman carried on with what he intended to do, dropping his bombs on the targets below. After helping his fellow Marines succeed in their mission, he now had to worry about making it back to base despite smelling like he was seconds away from falling out of the sky. He landed safely and added another close call to his extraordinary combat record.

Aside from his two Distinguished Flying Crosses and 13 Air Medals, one of Coleman’s most notable wartime service accomplishments was being the only active Major League Baseball (MLB) player (New York Yankees second baseman ’49 to ’57) to fly combat missions in two separate wars, 120 missions in total. (Boston Red Sox legend Ted Williams served stateside during World War II but only flew combat operations in Korea.)

At the time, professional athletes shared a bond few could relate to, leaving their prime years behind as no pennant race, World Series victory, or personal MLB record was too important to prevent them from joining the fight and serving their country. Coincidently, Coleman and Williams may have sported rival uniforms on the baseball diamond, but they were brothers in arms wearing the same flight suits in Korea.

“I [will] love baseball until the day that I die, but my time in the Marines was more important … I have felt from day one there are only one set of heroes in this country, and they’re all dead. Maybe the Medal of Honor people can overcome that, but the rest of us were just doing our job.”

Their antics of ball-busting carried over onto the tarmac and, in one instance, during the crash landing of one of Williams’ flights after a mission. On Feb. 16, 1953, Williams took enemy fire, causing his wing to burst into flames. He lost his radio communications and hydraulics but was in good enough shape to attempt a landing at the base. His wingman John Glenn, who went on to serve as an astronaut with the distinction of being the first American to orbit earth, motioned for Williams to enter thinner air to put out the fire.

With no flaps or wheels, Williams glided to the airport and prepared for a hard and ferocious crash landing. Williams’ F9F “Panther” plane skidded across the runway on the belly of the aircraft as the sparks lit the wings on fire a second time. Williams sprung free from the cockpit and sprinted away unharmed. Once Coleman saw Williams was safe, he blurted out, “Hey Ted, that’s a lot faster than you ever ran around the bases!”

Marine Aviator to New York Yankees Dynasty

Coleman reflected on his feelings following the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, saying they mirrored how he felt on Dec. 7, 1941, nearly six decades prior.

“Up until then all I wanted to do was be a professional ballplayer,” Coleman said. “From that day forward, though, all I wanted to do was get into the war and fight back. We got kicked in the ass on Pearl Harbor, and like all Americans, I was mad as hell. Maybe a little young and dumb, too, but I couldn’t wait to enlist.”

Upon the ending of the Second World War, Coleman transferred to the inactive Naval reserves and took his absence from the diamond in stride. In 1949, the New York Yankees made him their starting second baseman. He got to play among some of the greatest Yankees of all time, many who would go on to have their name immortalized in Cooperstown. Joe Dimaggio was viewed as a god, Yogi Berra as an icon, and Whitey Ford earned the nickname “Chairman of the Board” for his ice-cold persona that never relented on the mound.

Coleman soon became a reliable contact hitter, accumulating 21 doubles, five triples, and 42 runs batted in (RBIs), and he was named American League Rookie of the Year in 1949. The following year, he received All-Star nods as well as his first World Series ring, and earned a World Series MVP award for his near perfect infield performance of .977 percent. The Yankees three-peated victories between the 1949 and 1951 seasons, largely due to having five future hall of famers on the field at one time.

His next season was nothing more than mediocre at the plate, and the next two years were foregone when the Korean War erupted between 1952 and 1953. Eye issues, a broken collarbone, and lagging injuries cost him his best years, though his most significant highlights belong to his time with the Yankees dynasty competing in six World Series’ — and winning four of them — before retiring from baseball in 1957.

The Master of the Malaprop Was Born

While Coleman had a successful career with the New York Yankees, his most coveted role was as a play-by-play MLB broadcaster beginning in 1960 with CBS Network; he referenced this as “the greatest accident of his life” as he never expected to turn a weekend gig into a 40-plus-year career.

From 1963 to 1971, he kept seasoned baseball fanatics intrigued while also appealing to newer and younger viewers. Beginning in 1972 — except for a brief stint as the manager of the Yankees in 1980, leading them to a sixth-place finish — Coleman became the voice of the San Diego Padres for more than three decades.

Half the entertainment in watching baseball on TV — aside from the homeruns, stolen bases, and electrifying acrobatics from fielders — is the amusement we get from inside the announcers booth. Turning a mind-numbing blowout against a last-place team already out of contention for the playoffs into primetime television is what separates the greats from the forgotten. Coleman was the epitome of sports broadcasting and energized generations with his popular catch phrases — “The natives are getting restless,” “Oh, Doctor!”, and “You can hang a star on that one baby!” — to his masterful malapropisms, or “Colemanisms,” that he became famous for.

A malapropism is misusing words for a humorous effect, often spoken without intent, leaving an embarrassing trail of laughs and doubletakes from others. Coleman’s longtime friendship with teammate Yogi Berra must’ve rubbed off on him when he got into broadcasting because “Yogi-isms” were all too present during their playing days, which often left Berra at the brunt of the joke.

On one play involving right fielder Dave Winfield (now a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame) chasing a fly ball toward the outfield wall, Coleman remarked, “Winfield goes back to the wall, he hits his head on the wall, and it rolls off! It’s rolling all the way back to second base. This is a terrible thing for the Padres.” We know Coleman was referring to the ball, but the humorous visuals his words elicited kept fans craving more.

Nobody was safe from Colemanisms. He commented on the players’ appearance (“On the mound is Randy Jones, the left-hander with the Karl Marx hairdo”), pitchers loosening their arms to enter the game (“Rick Folkers is throwing up in the bullpen”), and made wisecracks (“If Pete Rose’s streak was still intact, with that single to left, the fans would be throwing babies out of the upper deck” and “There’s a hard shot to Johnnie LeMaster, and he throws Bill Madlock into the dugout”).

In the 2000s, Coleman was inducted into more halls of fame than World Series rings on his right hand: the San Diego Padres Hall of Fame in ’01; the U.S. Marine Corps Hall of Fame in Quantico, Virginia, in ’05; that same year he was awarded the Ford C. Frick Award presented annually to broadcasters “for major contributions to baseball” and inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s broadcasting wing; the National Radio Hall of Fame in ’07; and the International Air & Space Hall of Fame in 2011.

On May 26, 2008, while receiving a plaque dedicated to him at Mt. Soledad Veterans Memorial in San Diego, California, Coleman said, “I [will] love baseball until the day that I die, but my time in the Marines was more important … I have felt from day one there are only one set of heroes in this country, and they’re all dead. Maybe the Medal of Honor people can overcome that, but the rest of us were just doing our job.”

In 2014, Coleman died at the age of 89, but his memory and legacy will stand the test of time.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.