Tim Kennedy Reveals What the Fall of Kabul Was Really Like in New Memoir

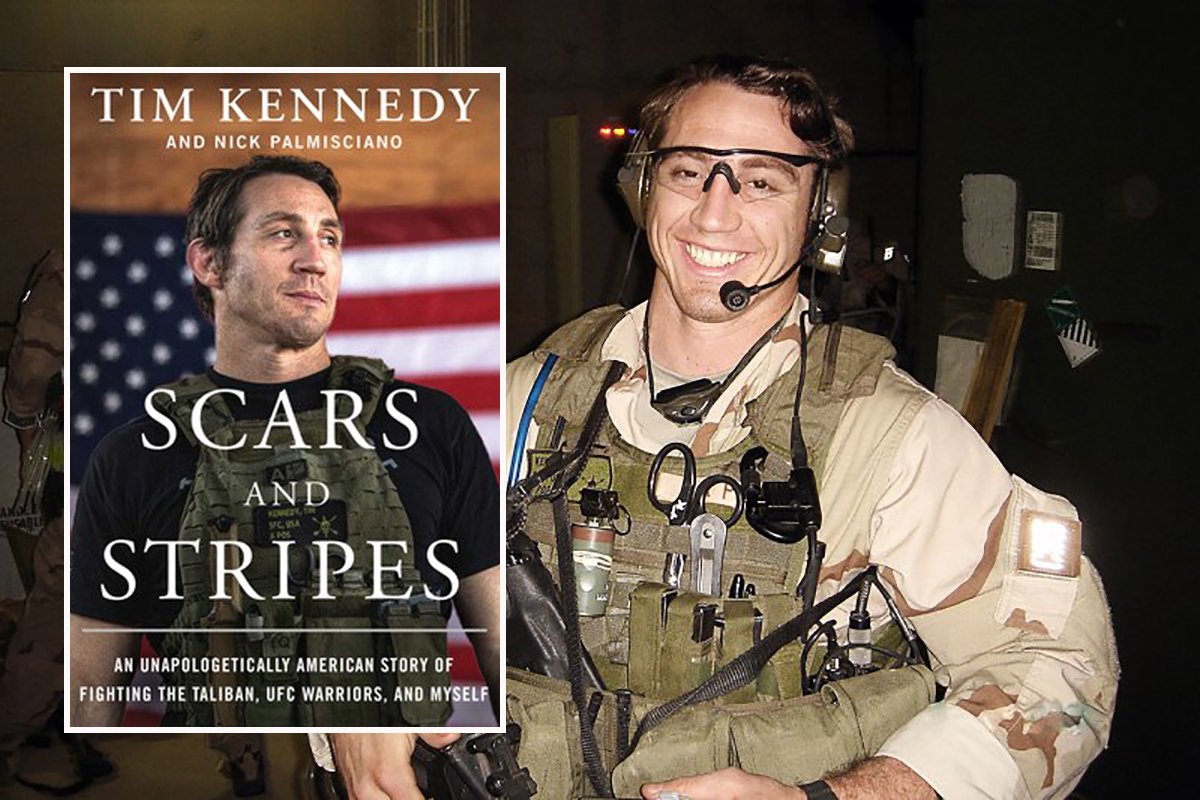

Tim Kennedy’s new book Scars and Stripes recounts the final days of the Afghan withdrawal. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Green Beret. Sniper. Combat veteran. Television star. Cop. Firefighter. Professional UFC fighter. These are just some of the many titles that apply to Tim Kennedy. And now, with the release of his new memoir, Scars and Stripes: An Unapologetically American Story of Fighting the Taliban, UFC Warriors, and Myself, we can also add “author” to that list.

In telling his own story, Kennedy humorously recounts the many trials and errors he negotiated as he climbed his way to success in the military, in business, and in his personal life. But for all the wild, self-deprecating stories crammed into the 416 pages of his debut book — including how he got two women pregnant in four days, and how his own Special Forces team once beat him up for being an asshole — it is the book’s final chapter about the fall of Kabul that elevates Scars and Stripes beyond a funny airport novel.

In August of 2021, as the world watched the Taliban retake Kabul with ease, Kennedy was busy hatching a plan to help evacuate people in Afghanistan who were especially vulnerable to retaliation from the new regime. As part of a 12-man team made up of former operators with aliases like “Santa 6” and “Seaspray,” Kennedy helped charter a private jet to fly to Hamid Karzai International Airport.

Upon landing, Kennedy recognizes the familiar swagger of a special operations veteran.

“Three dudes walk up, all reeking of Special Operations,” he writes. “Operators move differently. They talk differently. They seem chill and on edge, all at the same time. They still maintain the bravado of the infantryman, but it’s more relaxed — almost laissez-faire in nature.”

The “three dudes” greet Kennedy’s team with enthusiasm and give them AK-47s, night vision optics, and maps of the airport. From there, the 12 volunteers are essentially given free rein to do whatever they can for the orphans, government workers, and stranded Americans they’d come to help evacuate from the imploding country. They immediately find a hidden path that they can use to sneak evacuees past both Taliban and American checkpoints to the airport. Despite the Taliban’s outward show of humanitarianism, the group remained as ruthless as they’d proved to be since their inception. At one point, Kennedy watches Taliban fighters snatch a woman attempting to reach the airport and then lay her across the hood of a car and shoot her in the head. The Taliban know the Americans assisting her are under orders not to engage them, and they act mercilessly and with impunity.

The team eventually manages to get several buses packed with American civilians, orphaned children, and some government employees through the various checkpoints and inside the airport’s perimeter. But because they do so as civilian volunteers and without coordinating with the American military commander on the ground, they are ultimately turned around. Kennedy pleads with the unnamed lieutenant colonel, but eventually he relents.

“In my entire life, I have never seen a more pointless display of authority,” he writes of the call to force the loaded buses back outside the airport, dooming many of the passengers.

Kennedy goes on to describe the chaos at Abbey Gate as young American troops struggle to keep order and safely evacuate as many people as possible.

“I feel incredible pain for the soldiers and Marines guarding these walls,” he writes. “They’re playing God right now — deciding who lives and who dies — and I know that will weigh on them for the rest of their years.”

At the gate, Kennedy sees his own share of horrors. He witnesses mothers passing their infants over the sea of strangers like beach balls at a concert in last-ditch efforts to get them over the fence so they might have a chance at a better life. Kennedy recalls some mothers making even more desperate attempts to save their children: “In the worst cases, mothers throw their babies over the wall, hoping someone will catch them on the other side. Instead, those children hit the concertina wire on the inside of the wall and bleed out.”

Kennedy and his hodgepodge team of former operators were still at the airport when Abbey Gate was targeted by a suicide bomber on Aug. 26, 2021, killing the last 13 American service members to die in the 20-year war. Among the dead was a young Marine sergeant, Nicole Gee. Gee had helped Kennedy earlier that day when the team needed a female to help search women they were attempting to assist.

“She was really sweet, and high energy. She wasn’t going through the motions — she greeted every Afghan with a smile,” he writes. “She loved her job and her service.”

Kennedy claims that, in just a matter of several days, and despite their initial evacuation attempt being thwarted, his 12-man team helped successfully evacuate 12,000 people — a staggering 10% of the total number of people who were evacuated from Kabul. His efforts during the evacuation make the perfect final chapter to a book filled with ventures — some successful, others not — in the Army, in the ring, and at the business table. Kennedy never shies away from his shortcomings, and instead offers readers an alternative perspective to the many failures we all experience in life.

“Failure isn’t final,” he writes. “It’s necessary. It’s the fuel that allows you to advance, to succeed.”

Scars and Stripes: An Unapologetically American Story of Fighting the Taliban, UFC Warriors, and Myself by Tim Kennedy and Nick Palmisciano, Simon & Schuster, 416 pages, $30.

Read Next:

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.