The Triple Nickles: The All-Black Airborne Smokejumping Unit That Parachuted into Forest Fires

Officers of the 555th Parachute Infantry Regiment pose for a photo while at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Photo by Maj. Thomas Cieslak/3rd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division, courtesy of the U.S. Army.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor wasn’t the only time the Japanese struck U.S. soil during World War II. In response to the Doolittle Raid — the successful penetration of Japanese airspace and the bombing of strategic targets in Tokyo from the allies — the Japanese executed their revenge. The date of the launch was chosen for the birthday of former emperor Meiji, Nov. 3, 1944.

However, instead of using airplanes, the Japanese used fusen bakudan, or balloon bombs, that each carried four incendiaries and a 33-pound, highly explosive anti-personnel fragmentation device. The Fu-Go balloon bombs traveled 7,500 miles along the Pacific Ocean jet stream at altitudes between 20,000 and 40,000 feet. Witnesses described these large, white balloons as “giant jellyfish” floating in the sky. Their main objective was to start forest fires, create security doubts among the civilian populace, and cause upheaval.

The all-black Triple Nickles battalion was ultimately responsible for combating the slow-moving, round balloon bombs, which had no escort or protection and had been spotted by the U.S. Navy patrol off the coast of California only two days after their initial launch. The patrol alerted the FBI, and investigations were conducted to find the origin of these mysterious flammable balloons traveling over the Pacific Northwest and into Canada.

Paratroopers from the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions suffered heavy casualties in the European Theater (ETO) during the Battle of the Bulge and the courageous siege of Bastogne; they were in a desperate need for replacements. The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, or the “Triple Nickles” as they became known, trained to fulfill this capacity. However, as with other all-black units of the time, African-American soldiers weren’t treated equally. “We were relegated to serving in menial units such as truck drivers, port companies (loading ships), mess halls (waiting on tables) and guard duty,” wrote Walter Morris, a Triple Nickle veteran.

Although no Triple Nickles completed a combat jump or deployed to Europe, these trendsetters provided another example of how an elite all-black unit could be employed in a combat or peacetime environment. The Triple Nickles participated in a top-secret project fighting forest fires as the U.S. military’s first smoke jumping paratroopers over the Pacific Northwest.

The Triple Nickles, a name derived from the parachute regiment’s designation, was created in the winter of 1943 and consisted of 17 of the original 20-man platoon from the 92nd Infantry (Buffalo) Division. These men were hand-selected to create the first “colored test platoon.” A few months into 1944 saw newly minted paratroopers who completed training jumps at Fort Benning, Georgia. The first all-black parachute infantry battalion in history had formed but were still brand-new and lacked manpower. The paratroopers honed their skills and became experts in small-unit tactics.

Several went to the best schools the U.S. Army had to offer. Some became riggers and jump masters while others learned the metrics in communications, the skills to navigate difficult terrain as pathfinders, and the intricacies in demolitions.

They were the cream of the crop — college graduates, professional athletes, men of high character and extraordinary intellect. One Triple Nickle veteran, “Tiger” Ted Lowry, entered the ring to face world champion boxing legend Joe Louis, who came to Lowry’s base in 1943. He was accompanied by Sugar Ray Robinson — who Muhammad Ali coined as “the king, the master, my idol” — when the duo toured military camps to entertain soldiers. “Stay in the middle of the ring,” Robinson advised Lowry, “don’t let him get you on the ropes.” Lowry already had 70 fights to his name and somehow survived the three-round exhibition with one of the greatest boxers in history.

“You can’t imagine what that did for my ego,” Lowry reflected. “I had just been in the ring with the champion of the world, the greatest fighter in the world, and he was unable to knock me down. My confidence was inflated.” His fighting days halted when he joined the Triple Nickles but resumed when he faced Rocky Marciano, the Brockton, Massachusetts, undefeated heavyweight champion. Not only did he stun Marciano, but he shocked crowds of hometown Italian-Americans by going the distance twice with the Brockton Blockbuster, the only fighter ever to do so.

When World War II was nearing a close and as the Germans were losing ground, the Triple Nickles’ focus shifted from Europe to the homefront. The Triple Nickles were the size of a “reinforced company” but expected to reach battalion size by 1945. The threat from the Japanese balloon bombs was imminent, and they were diverted to Pendleton, Oregon, and Chico, California, under secret orders to the 9th Services Command.

The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) received help from the U.S. Army when 400 paratroopers from the Triple Nickles were tasked with the difficult job. They turned in their rifles, hand grenades, and rucksacks. In that equipment’s place they donned football helmets with wire face masks, equipped 50 feet of nylon rope for lowering themselves from trees, and packed firefighting tools such as axes and handsaws on their person for parachute jumps.

The smoke jumping program was in its sixth firefighting season, but the war dwindled their resources, and the Triple Nickles provided a welcome skillset. Pilots flying C-47s needed no additional training and had prior results in properly managing smokejumper assets in remote regions where fires were often inaccessible by roads. The response and defensive strategy against the Japanese balloon bombs was a little-known secret called Operation Firefly.

Later reports suggested that the Japanese launched over 9,000 helium balloons. Damage from these balloons was rare but noteworthy. One balloon exploded after it hit high-tension power lines that were connected to a plutonium plant in Hanford, Washington. It caused a temporary blackout to the community, and the plutonium plant was ironically responsible for developing the fuel for the atomic bomb dropped over Nagasaki, Japan.

Vincent “Bud” Whitehead, a U.S. Army counterintelligence officer, used to track and chase the balloons in the air from his plane. In March 1945, a balloon had landed on the ground but didn’t ignite. “They sent a bus up with all of this specially trained personnel, gloves, full contamination suits, masks,” Whitehead said in an interview with the Voices of the Manhattan Project. “I had been walking around on that stuff and they had not told me! They were afraid of bacterial warfare.” Biological and bacterial warfare fears were not exaggerated because it was later revealed that the Japanese had scrapped an operation at the end of the war for weaponizing the bubonic plague.

Another notable tragedy that involved these balloon bombs was the devastation of almost an entire family while they picnicked near the Gearhart Mountain in Bly, Oregon. On May 5, 1945, Reverend Archie Mitchell, his pregnant wife, Elsie, and five children from their Sunday School class were victims of the balloon’s lethality. The children went to investigate the strange object that had floated to the ground, but they got too close and were killed when the balloon did what it was designed to do. Archie Mitchell was the only survivor.

The Triple Nickles went to work to prevent additional American civilian casualties. First Lieutenant Edwin Willis, a brilliant planner and training specialist, put his paratroopers through a three-week crash course to learn proper firefighting knowledge and techniques. Willis received assistance and guidance from USFS smokejumpers and forest rangers as well.

This course included “demolitions training, tree climbing and techniques for descent if we landed in a tree, handling firefighting equipment, jumping into pocket-sized drop zones studded with rocks and tree stumps, survival in wooded areas, and extensive first-aid training for injuries — particularly broken bones,” said Morris.

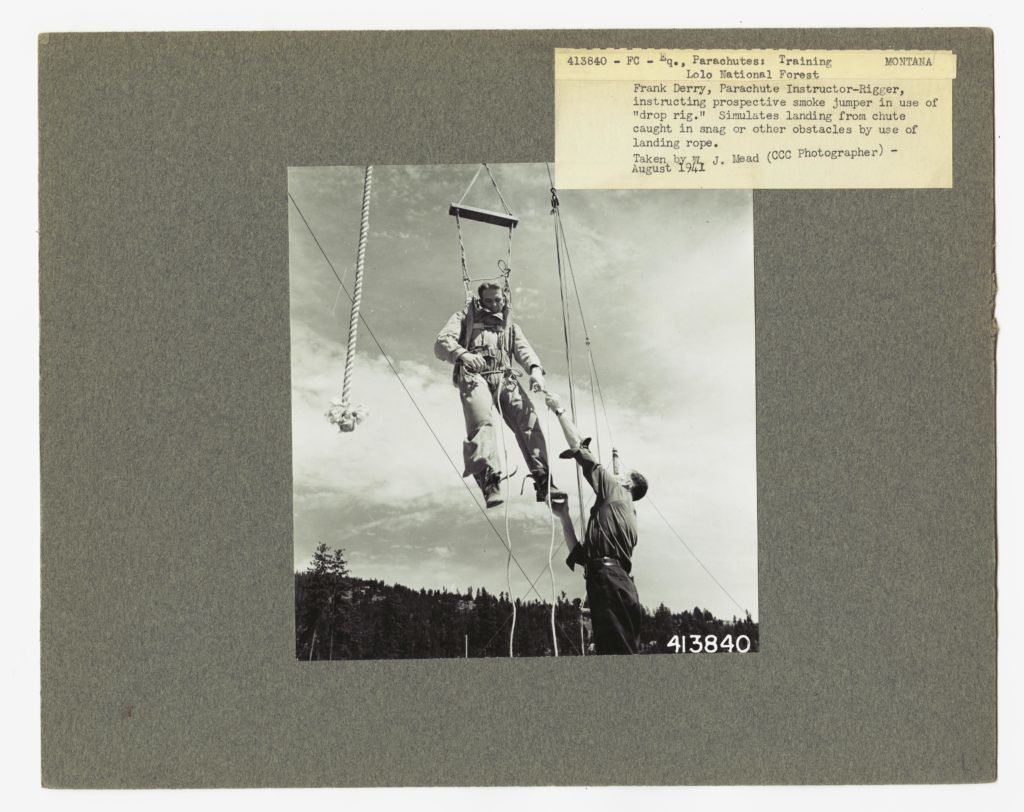

Frank Derry, a master civilian parachutist, issued the Triple Nickles his “Derry-chute,” which was known for its maneuverability and steering capabilities. “Snag trees, those were the worst. I didn’t like those dudes at all,” Derry said, referring to the nuisances found in their path. “But landing in the trees was just as soft as landing, better than landing on the ground. The thick trees […] you just come into them like sitting down on a pillow, nothing to it.”

The Triple Nickles were also assisted by demolition experts from the 9th Services Command and USFS rangers. “Learning the touchy business of handling unexploded bombs, as well as how to isolate areas in which a bomb, or suspected bomb, was located,” Morris wrote. The incedinaries and chemicals were an additional pucker factor to their already challenging task.

The Triple Nickles also learned to live off the land and avoid costly mistakes that could derail their mission. “They could walk up the hills like a cat on a snake walk,” Morris wrote, discussing the expertise of USFS rangers. “They taught us how to climb, use an axe, and what vegetation to eat. At the same time, we underwent an orientation program with Forest Service maps. And, above all, our morale and spirit of adventure never sagged in the face of this unusual mission.”

The Triple Nickles became fully operational smokejumpers, but the numbers on how many fires and fire jumps they completed have been skewed over the years. Chuck Sheley, the editor of Smokejumper Magazine, states they completed 460 to 470 jumps on an estimated 15 of 28 forest fires, while they drove or hiked into the other fires. The National 555th Parachute Infantry Association consensus estimates the Triple Nickles answered 36 fire calls with 1,200 individual jumps across seven Western states.

Private First Class Malvin Brown was the only casualty of the Triple Nickles. Brown was a critical component of the team because of his medical expertise. Any injuries, accidents, or potential concerns went through the fire medics. When 15 Triple Nickles paratroopers boarded their C-47 on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, Brown wasn’t supposed to be there. However, he volunteered to replace another medic who was sick. Hours later he jumped into a fire in Umpqua National Forest in southern Oregon’s Cascade Range and landed in a tree. Moments later he slipped and fell more than 150 feet to the ground below. He died instantly.

Brown’s fellow smokejumpers changed their mission from fighting the fire to bringing home their teammate’s body. After an arduous search in rocky terrain, they located him and carried him more than 3 miles through the backcountry. Their first sign of civilization was a trail, but it took another 12 miles for them to find a road to get help.

The soldiers of the Triple Nickles weren’t respected while they were in service, but their contributions in a long lineage of elite all-black units are remembered as if they were legends. The Triple Nickles disbanded after World War II, but many of the soldiers continued to serve, including Lieutenant Colonel John Cannon, who was a combat medic during the Korean War. John E. Mann served as an Army Special Forces advisor in Vietnam and was awarded the Silver Star, three Bronze Stars, three Legions of Merit, and a Distinguished Flying Cross. Mann served in the military for 33 years and later authored four detective novels.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.