The author, left, and his classmates in the schoolyard after the attack. Photo by Mian Khursheed/Reuters.

The sound of gunshots echoed through the school, bouncing off the walls like a demon roaring just around the corner. The school was an old, hollowed-out church, and with all the hard walls and vinyl tile — the same surfaces that easily echo children’s laughter — the gunfire was amplified.

It was Aug. 5, 2002, in the small town of Murree, Pakistan. I was hiding under a desk in the library of a British boarding school. Murree Christian School offered an English-speaking education for the children of missionaries, aid workers, government workers, and others who might be interested in their children having an opportunity for a higher education back in the West once grade school was done. The world was on edge after 9/11, and when the US invaded Afghanistan, the Taliban flooded across the border into Pakistan, bringing their brand of violent unrest with them.

It was that unrest that brought four gunmen to Murree Christian School. It was the second Monday of eighth grade, and I was still figuring out where all my classes were. My brother was a senior who had attended the school for several years, and my mother was visiting.

A girl under a nearby desk was quietly sobbing; another boy was whispering prayers under his breath. Many of the other students were quiet, frozen in fear, confused, unsure what they could possibly do to help. I hugged my knees under my desk and wished that I was something more than a scared child.

Pakistani military men inspect bullet holes in a cafeteria after an attack by unidentified gunmen on Murree Christian School on Aug. 5, 2002. Photo by Mian Khursheed/Reuters.

My eyes were plastered to the enormous library windows looking into the school’s interior. The only door in the room lay directly in the center of those windows, and anyone hoping to open it would have the spotlight for several seconds as they traversed the glass to get to the door. My attention occasionally drifted elsewhere when I felt I could do even the smallest things — I held the hand of the crying girl for a while, I cracked a few dark jokes with another friend. But my eyes would always snap back to those windows, waiting to see a rifle-toting figure who would push open the door and end everything.

Then I saw it. A human figure. My heart shook as adrenaline shot through my body, but I sat frozen under the desk.

I didn’t know how to fight, there was nowhere to lead myself or others to safety, and I couldn’t think of anything I could do to help. An overwhelming sensation of raw energy washed through my body and mind as I waited to die.

When I saw his face, the wave of fear was replaced with one of relief. It was an older student desperately trying to find his little sister. She was a few desks over, so I pointed him in her direction.

People react in all sorts of ways when bullets start getting tossed around. I learned that at a very young age, and I would learn more about it later. Some start weeping desperately; others put on a stone face and refuse to move. A few, who are just as scared as the rest, embrace a little dark humor to pass the time — that was me and my friend Simon.

I was never the vandalistic type, but on that day Simon and I etched under the desk: “Simon Baron + Luke Ryan hiding from terrorists, 5 August 2002.” We chuckled and hoped it wouldn’t be our last laugh.

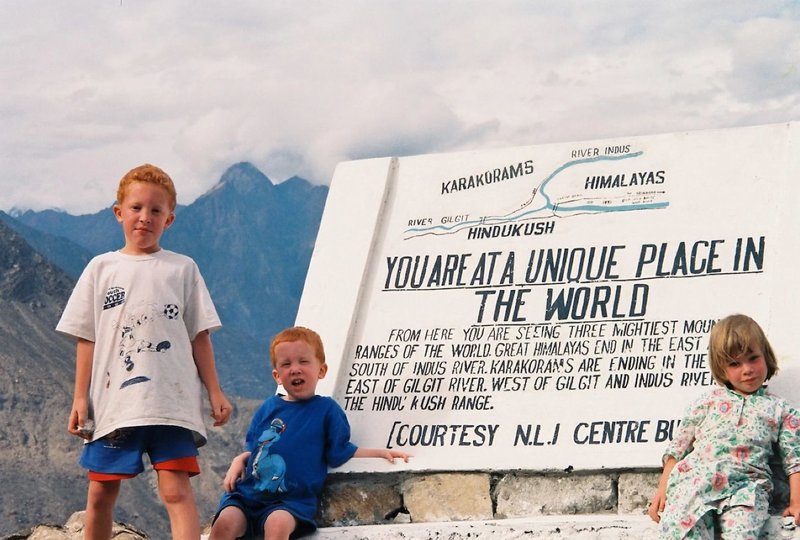

The author, center, his brother Josh, left, and a friend in northern Pakistan. Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

At first, the gunshots thundered and shook the school’s stone walls. Eventually, the bass from the shots diminished and sounded less like a roaring demon and more like pieces of plywood slapping against each other as the shooters drew farther away. I don’t remember the last shot being fired, just the volume knob turning down slowly over the course of an undefined period of time. It could have been 10 minutes; it could have been four hours.

It wasn’t long before Pakistani military and law enforcement personnel flooded the school grounds, carrying rifles and body armor and other equipment unknown to me at the time. I had only peeked out of a window for a couple of seconds during the attack, so most of my time was spent staring at the interior windows of the library and studying the underside of my desk. That morning, it was an overcast, rainy day, with indifferent students bumbling from one class to the next; now, it was the center of a coordinated military operation with terrorists on the run in the vicinity.

Casualties were carted to an indoor basketball court right next to the library, and I remember my friend’s mother screaming as blood poured from a gunshot wound to her wrist. She would survive, but six others would not.

Thankfully, and by a series of miracles, no children were killed. Weather, a time discrepancy in planning, and a few other circumstances made the gunmen’s operation a tactical failure. Looking back, I suspect they were also afraid and probably rushed through the area much faster and more clumsily than they’d planned.

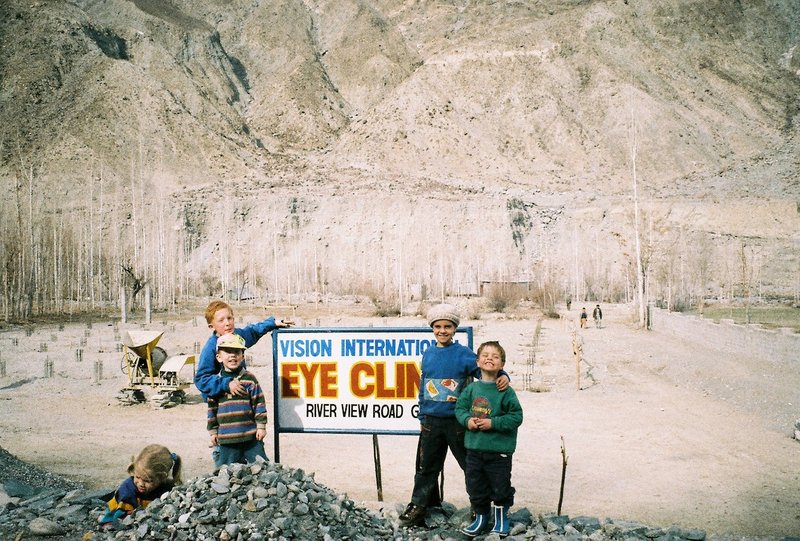

Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

Hours after the shooting, one of my British friends and I circled around the front of the school near where the terrorists had breached the compound’s gate. We found blood and bits of flesh splattered against the old stone wall and running onto the ground. It would have been easy to notify an adult about the situation, who could have gotten it cleaned up in a heartbeat.

But there was a hose nearby, so we sprayed the place down. We did it with care, understanding the gravity of our actions. We washed off the wall and pushed the blood into a patch of nearby earth. The wall was clean again.

When I tell that story, a lot of people think of how traumatic it must have been to clean human blood off a wall in the second week of eighth grade. Maybe it was on some level. But it was also the one moment where I actually felt like I had some form of agency — that even that small action mattered in a hurricane of chaos.

The attack on my school was not a primary motivator for me to join the military. At least not consciously. It did, however, give me a perspective that most of my peers in the Army didn’t share: I felt I had already seen enough violence.

During basic training, there was a brief and false rumor that we were going to war with North Korea. Some would-be soldiers were ecstatic, ready to put their newfound skills to the test. While I understood their mindset I did not share their enthusiasm. I was aware that a heroic-minded man might take a bullet to the neck as the first boat ramp lowered. I knew the bravado in those beating chests was as useful as the hot air coming out of their mouths, and that a dangerous quiet man was just as deadly as a dangerous loud man — noise has nothing to do with it. I knew a lot of kids would be hosing down a lot of blood in a country I didn’t know much about. I would serve the country I had grown to love, but a war would not bring me joy.

Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

Nonetheless, I chose a profession that took me back into the purest, most awful form of human struggle. The US was winding down the war in Iraq, and the pressure was back on Afghanistan. I knew if I passed all the required training and selection courses to join the 75th Ranger Regiment, I’d likely find myself fighting just a few hundred miles from my old home in Pakistan.

The first time I was in a firefight, I didn’t have a weapon. The second time I was in a firefight, I had a weapon — but I didn’t have to use it.

In early 2011 I was sleeping in a room on the lower level of a building my Ranger platoon had taken from the Taliban in the heart of Zabul province, Afghanistan.

Taking the compound the night before hadn’t been difficult. It was mostly vacant when we breached their doors and cleared each room with the precision and methodology that had been hammered into us. There were a few women and children, but the male Taliban fighters had departed.

I overheard the interpreter say that the building had been a school before the Taliban commandeered it and turned it into a stronghold. That didn’t mean much to the guys there — it was a stronghold now and that was the end of it — but it meant something to me.

The plan was to bait the Taliban into a fight and then respond accordingly. Our compound was a series of two-story buildings nudged up against a large, exterior wall, and those who kept watch found pieces of cover along the rooftops to look outward into the neighboring town and terrain. The Rangers who slept took refuge in the lower level, nestled in the heart of the compound. We had a good position, and we knew it.

Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

Just as time had passed differently at Murree Christian School a decade earlier, it passed differently in the Taliban stronghold. I don’t remember what time it was when I heard the first explosion. I do remember the sound of gunfire and leaping out of my sleep and into my kit. I remember seeing my squad leader put his things on at borderline impossible speeds. I remember my MK46 in my hands as I moved through the compound to support those around me. I left the room and climbed a nearby ladder to reach my friends, already returning fire from the rooftops.

A rocket shot over our heads and slammed into a mountain behind us. A few poorly aimed mortar rounds exploded nearby, spitting up great bursts of dust and debris. Gunfire spit at us from a remote fighting position, but the distance between us and our attackers made most of the fire ineffective.

A familiar fear crept back in. It was the same fear that had washed through me as a child.

Standing just outside a wall, I craned my neck to see if there was a spot on a nearby rooftop to lie prone and lay out some lead. I wasn’t exposed to the known enemy, but I was exposed at most other angles — a rookie mistake made by a rookie soldier. As my first sergeant happened by, he asked sternly, “What’s between you and a bullet?” not waiting for the answer.

I swung around into a nearby doorway and pulled security out over an exterior wall that dipped lower than the rest. From there, I watched my sector of fire for the next hour or so.

Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

My job would not lead me to fire my weapon that day. That would come later. Still, I had a thousand tasks: pull security, stay aware of my team and squad who were bouncing between rooftops, stay behind cover, ferry ammunition and equipment if necessary, maneuver when ordered. I knew how to do each of those tasks, and I poured myself into them. My fear was simply pushed aside by a knowledge of what to do and how to do it.

During my first firefight in Afghanistan, I had something I didn’t have when I took shelter under that desk in the eighth grade. It wasn’t courage or the desire to stand up against those who would do harm to people I loved. It wasn’t my age, nor was it toughness or the ability to endure great suffering.

It was much simpler: Usefulness. Utility. And it made all the difference.

That exchange of bullets from the Taliban stronghold was not my last firefight. I pushed through four combat deployments to Afghanistan, each separated by a Ranger training cycle. Those training cycles are dedicated to shoving as much tactical knowledge down your throat as possible in the shortest period of time possible. I learned how to fire my weapon, and when I had to fire it, I was accurate and competent. I learned how to load and carry a portable litter, and when my friends were hurt I was able to do my part in getting them to safety. I learned how to lead a group of Rangers onto an objective and complete our piece of a mission. The fear was always there, but the more experience I earned and the more tools I was given, the less the fear mattered.

The author in Afghanistan in the winter of 2011. Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

But I wasn’t interested in the rest of my life revolving around violence, so I left the military and chose to pursue a life of creativity. I wanted to make movies, write books and poetry, and fuel a creative side of me that was yearning to be let loose. The first step in that journey was to get my degree in English literature from the University of South Florida.

In the fall of 2014, I was leaning back in my chair in a literature course surrounded by about 20 other university students. I still had something of a baby face, so I blended in with the 18- to 22-year-olds, most of whom had gone straight to college after high school. I listened intently to the professor and scribbled notes — I had a newfound love for reading and learning that had been fueled by my stint in the Army.

We were studying “The Open Boat,” a short story by Stephen Crane. I knew nothing of Crane’s life, but as I flipped through the pages the author’s words resonated on a deeper level than I had expected. The story is about four survivors of a shipwreck who are floating on a dinghy, hoping to find land or be rescued. It’s a simple premise, but it struck a chord in my heart.

Our professor went on to explain that Crane was speaking from experience. The story was fiction, but Crane had actually survived the sinking of a boat and spent about 30 hours at sea fighting to survive. When he found his way home, he put that experience into words. As the saying often attributed to Ernest Hemingway goes, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” Crane bled onto those pages, and I could feel it.

Photo courtesy of Luke Ryan.

The discussion between the other students and the professor encompassed broad, emotional themes, speaking of brotherhood, a loss of control to nature, and the power of near-death experiences. I agreed with her points on all of those themes; in fact, those are the things that have made “The Open Boat” one of my favorite pieces of writing.

But it was the physical details that called to me. The effects of the waves on the boat. The iciness of the water in January. The strength of the current. It was the crew’s ability to navigate those real circumstances that led to at least a few of them surviving. “Speech was devoted to the business of the boat.” Crane talked about the difficulties of changing seats on the dinghy, how they were all physically positioned, their rest plans, the nature of the wind — these practical considerations are important to the story and meant so much to me, but I didn’t know why.

There, in a dark classroom lit by a projector with Stephen Crane’s face plastered on the screen, two chaotic, violent moments of my life spoke to me. We live in a practical world, and it’s only practical skills that will see us through it. Whether it’s picking up a hose or picking up a rifle to protect those we love, the intangible qualities that we value, that are necessary for success — discipline, passion, focus, innovation, creativity — they amount to a single, tangible attribute: usefulness.

However, the chapters of my life defined by violent but clear objectives are at an end.

So, how can I be useful now?

This article first appeared in the Spring 2022 print edition of Coffee or Die Magazine.

Read Next: How a Purple Heart Recipient Conquered the Seven Summits

Luke is the author of two war poetry books, The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence, and a post-apocalyptic novel, The First Marauder. He grew up in Pakistan and Thailand as the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and deployed to Afghanistan on four combat deployments. Now he owns and operates Four Hawk Media, a social media-focused marketing company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.