The Valley Boys: How a Lone Special Forces Team is Fighting ISIS in the Remote Mountains of Afghanistan

A US Army Special Forces “A-Team” overlooks the Bagh Dara Valley in Nangarhar, Afghanistan during a combat patrol in 2018. Photo by Marty Skovlund, Jr./Coffee or Die Magazine.

Buck, a former US Army Ranger-turned-Special Forces communication sergeant, quietly watched as a C-130 cargo airplane lifted off from the runway at Jalalabad Airfield with a deafening roar, quickly ascending into the pitch-black sky.

“I know there’s a scientific explanation for it, but it still blows my mind every time I see it,” Buck said. “I mean, something that big just doesn’t seem like it should be able to take off like that.”

The lone operator was patiently waiting for his hour-long flight out to combat outpost (COP) Blackfish, located in Nangarhar Province’s Achin District, where the rest of his Special Forces team was deployed. Only 11 kilometers from the Pakistan border, the remote camp is one of the most forward positions the US military holds in the fight against ISIS-Khorasan.

Buck eventually boarded a single blacked-out aircraft and departed with little fanfare, heading east and high, quickly leaving behind the relative safety of a major US military base. The blackhawk weaved its way through a maze of rugged valleys while mountain ridges towered above. Speed is the best defense in such terrain — many US helicopters have been downed by enemy rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) over the course of America’s long war.

After a long, silent flight, the bird descended onto a makeshift helicopter landing zone (HLZ) unseeable to the naked eye; the stars above offered the only illumination. A figure in the distance motioned with a red-lens headlight, marking the entrance to the small compound. The helicopter lifted off again in a hurry.

The Green Berets of COP Blackfish are a dive team, meaning they go through all the training required of a Special Forces (SF) soldier but must also complete the notoriously difficult Combat Diver Qualification Course (CDQC) — which essentially creates another layer of selection in order to serve on the team.

They still fit the common tropes associated with SF though: beards, long-ish hair, and relaxed attitudes along with a few sleeve tattoos sprinkled in for good measure. Although they sport ball caps and Glocks in lieu of cowboy hats and six-shooters, they are frontiersman all the same — charged with taming the Mohmand Valley.

The team sergeant, Cotton, is an Indiana boy who looks like Jason Momoa. With multiple combat deployments to places around the world under his dive belt, he also served as the chief instructor at CDQC prior to assuming his role as the team’s senior non-commissioned officer (NCO). A sergeant’s sergeant, he’s of the opinion that if you go SF, you need to “earn all three lightning bolts” — which represent air, land, and sea on their unit patches. “Damn near every other special operations unit requires their guys to both jump and dive, why shouldn’t we?”

Other members of the team include Jeremy, the team’s senior medic, who knows firsthand what it’s like to receive one of the gunshot wounds he’s trained to patch up. Stoner, the team’s senior “Bravo,” or 18B weapons sergeant, has been deploying to Afghanistan since the weeks following 9/11. Buck, a native Idahoan who seems to be somewhat of an introvert, is the youngest — and one of the hardest working on the team. Chuck, another Indiana native, serves as one of the team’s engineer sergeants.

The team was augmented by Jaeger and Charlie, both hailing from different operational detachment alpha teams (ODAs). A coalition Special Forces soldier, Mark is a member of the team as well but is working on an exchange program that extends beyond their current deployment. Able, a Combat Controller on loan from the US Air Force, is most notable among the team’s attachments: he’s responsible for calling in fire missions day and night in order to keep bad guys off the ridgelines.

The team operates out of COP Blackfish, which is a nod to the team’s maritime roots. It’s not the large military installation you might assume would be in place after 17 years of war in the country. In fact, it’s a fairly recent addition to the coalition inventory.

The isolated outpost sits in the Mohmand Valley, a short walk from where the controversial “MOAB” was dropped last year. Prior to that explosion, US troops were not able to move this far into the then-ISIS-controlled territory due to an extensive network of caves that facilitated enemy troop movements and maneuvers, making any American incursion near-suicidal.

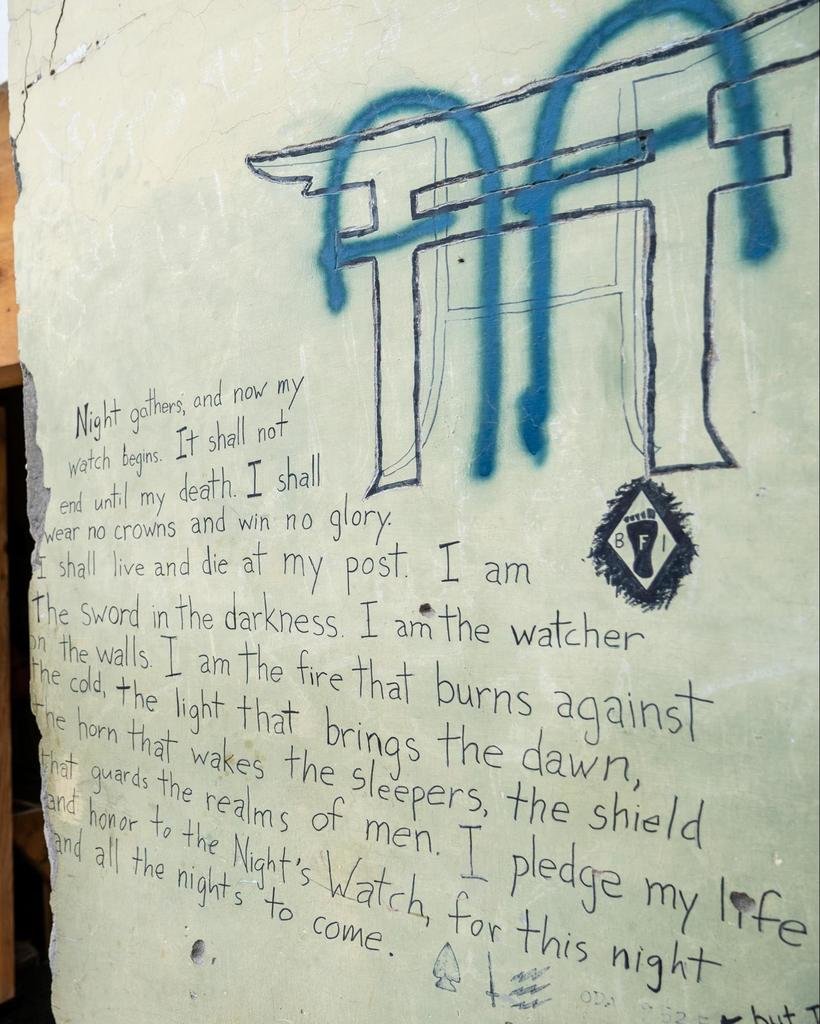

The camp itself consists of a traditional Afghan farm compound with extremist graffiti still present on the interior walls from when ISIS-K occupied it. Outside, a medium-size, Army-issue, general-purpose tent stands, surrounded by hesco barriers (which they filled by hand, using empty ammo cans as buckets) and a few rudimentary guard towers. All told, it’s just big enough to shelter the Special Forces team and a small element of their conventional Army brethren — often referred to as “uplift” soldiers.

“It’s pretty safe here,” one special operations officer told me, “until it’s not.”

Set in a valley surrounded by mountain ridges — the only terrain feature between the team and ISIS-K — and far from any other American military presence, COP Blackfish truly is a modern frontier outpost.

Food, water, and supplies are flown out to them inconsistently at best — sometimes once a week, sometimes every two weeks — and only at night. There is no dining facility; a “Meal, Ready to Eat,” or MRE, is on the menu twice a day. A frozen personal pan pizza or hotdogs and beans are used sparingly and for dinner only.

Bathroom facilities include a trio of PVC tubes inserted into the ground for liquids and “WAG bags” for solids. The bags, once one’s business is done, are sealed and placed into another slightly larger bag, then tossed into a full-size garbage bag with the other bodily waste. Although spartan, it’s a surprisingly efficient way to minimize foul odors on the small camp.

Their common area includes a movie screen (a white sheet) stapled to the plywood wall and a projector on the table, positioned center and back, hooked up to a laptop for evening movies. A Travel + Leisure magazine cover encouraging readers to “swing into spring — the best places to go this season” sat on the table.

The weather was deteriorating, and so the work day came to a natural close, allowing me time to get to know the team. As was the case almost every night, they gathered in the common area to make dinner — pizza with hot dogs sliced up and placed like pepperonis was the dinner of choice for most. Despite the arduous conditions, morale seemed high.

At some point, one of the power strips literally caught fire. It turns out that having the power cord run behind one of the countertop stoves wasn’t a good idea. They conceded that the setup was “pretty jenky,” while nonchalantly addressing the fire hazard.

“Who outranks safety? Nobody!” Cotton quipped. He wasn’t going to let the situation pass without contributing a little bit of standard NCO sarcasm. A quick response was delivered right back though, “Donald Trump does. Donald Trump definitely outranks safety.” Laughs all around; good conversation filling bouts of boredom is not a phenomenon exclusive to war, but the former is often enhanced by the latter. This late-May evening was no exception.

During their nightly briefing, Cotton informed the team that they had a pending “Five W’s” — aka combat mission — in the nearby Bagh Dara Valley coming up in a few days. The statement evoked nothing more than a few grunts about the weather (a frequent reason for missions being cancelled). A few more notes on the following day’s chores, and the briefing came to a close.

The team’s nightly custom was to watch a movie before going to bed, and tonight was no different. Jaeger put “Thor: Ragnarok” on the big screen for the evening’s entertainment. Hollywood tends to take a fair amount of criticism these days, but few understand how much their work can boost morale in a war zone.

The rain intensified, and lightning lit up the sky. Cotton and Doc Jeremy continued what seemed to be an ongoing struggle against leaks in their room while the movie played. On their fifth iteration of a solution to the water problem, a web of tubular nylon and sheets was rigged in order to direct leaking water into buckets. There was no shortage of this brand of ingenuity in the camp, although this wouldn’t be the last time Cotton had to fight the COP Blackfish water insurgency.

Just before midnight, after the majority of the team had already retired to their leaky quarters, the sound of automatic gunfire echoed through the valley.

“Tower, this is Blackfish. Did you get it?” the soldier on radio duty said.

Safe indeed — until it’s not.

You ever blow anything up before?”

Able’s question wasn’t borne of pure curiosity about my past interactions with explosive material; a few members of the team were going outside of the camp’s boundaries to take down trees via C-4 and Bangalore torpedoes.

The trees stood between Blackfish and a primary avenue of approach for ISIS-K, thus posing a security threat. They needed to fall with extreme prejudice.

The intent was to take them all down in one fell swoop, so it took Able and Charlie some time to rig the demolition charges. Det cord criss-crossed from tree to tree, connecting Bangalores attached via duct tape; C-4 explosive was pushed into every crevice of the trees’ trunks (C-4 is similar to thick playdough in consistency).

All told, over 50 pounds of explosives were rigged for the task at hand. Able and Charlie made a few final inspections before heading down the hill to find cover and put a little distance between them and the impending chemical reaction. Fragmentation is a concern no matter the size of a charge; “if you can see the charge, it can see you” is the general rule of thumb.

“Fire in the hole, fire in the hole, fire in the hole!” Charlie shouted at the top of his lungs, before pushing, twisting, and pulling the small ring on the M81 firing device that initiated the explosion.

The shot went off without issue. A small, gray mushroom cloud floated up to the sky, the report bouncing through the valley. After a not-so-close inspection, Able and Charlie declared the mission accomplished: The trees were obliterated.

“Whether your job was to drive a bobcat or blow up trees, everyone earned their keep.”

Back in the camp, Doc Jeremy was treating Chuck in the medical room of the compound. His day wasn’t quite as entertaining as his teammates who were tasked with blowing stuff up; while repositioning concertina wire, he fileted his arm open and the wound required suture. The epitome of a hard soldier, the engineer sergeant didn’t wince as his skin was expertly stitched back together. All in a day’s work, as they say.

Improving security and building up the outpost is a daily chore at COP Blackfish. The days are long, the sun intense, and the to-do list never seems to end. Neither rank nor status as a Green Beret excused anyone from labor; whether your job was to drive a bobcat or blow up trees, everyone earned their keep.

A five-minute drive to the north, a handful of soldiers from Blackfish lived in a small satellite post positioned just above where an ISIS black market used to be. This position kept eyes on the Takhto Valley, which was still occupied by militants. They reported over the radio that some local Afghan teenagers were digging holes on the road into their camp, backpacks in tow. With the very real threat of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in mind, Jaeger, Charlie, and Stoner loaded into a gun truck and went to inspect further.

Typically, this would be something that the Afghan soldiers assigned to them from the National Mine Removal Group (NMRG) would take care of or at least assist with. The ODA usually depended on them for route clearance, but they were on a short hiatus after losing one of their own who was digging up an explosive by hand. The ODA’s engineer sergeants had caught them doing this on multiple occasions in the past and had repeatedly chastised them about the unnecessarily dangerous practice — it was much safer (and easier) to blow the ordnance in place. The cash reward for digging them up unexploded is a strong incentive in a largely impoverished country though.

“I’m surprised by your choice in music,” Stoner said, making an observation about Jaeger’s contemporary playlist emanating from his iPhone as we drove. The song in question? Fergie’s latest pop hit, “M.I.L.F. $.” Jaeger casually responded, “I like all kinds of music,” as if it was a completely normal selection for a trip outside the wire.

The view from the small road we were driving up told a tale of its own. On one side, a green, lush valley teeming with local Afghans busy going about their day’s activities. The other side, still occupied by ISIS militants, was brown and desolate — the few buildings that remained were devoid of any signs of life. Just before my arrival at Blackfish, militants conducted a daytime raid into the prosperous side of the valley and beheaded a man in front of the locals. The evil act resulted in as many as 50 to 60 people evacuating the town.

Shortly after arriving and dismounting, the Special Forces soldiers conferred with a handful of uplift troops in order to identify the spot on the road where they saw the potentially nefarious activity. The wind whipped and whistled as dark skies threatened off in the distance. Afghanistan’s rugged mountain border with Pakistan had weather that was unpredictable on a good day. Only the week prior, Blackfish was flooded in knee-high water from a torrential downpour that arrived seemingly out of nowhere.

After a short hike to a bend in the gravel road, Jaeger moved ahead and began a cautious approach to inspect more closely. The ground had indeed been disturbed.

The wind speed picked up considerably and the sky darkened, spitting out bursts of rainfall, almost as if it were trying to warn of an imminent hazard ahead. Jaeger continued to close the gap between him and the disturbed gravel, moving well within the potential blast radius. To complicate matters, the radio signal back to the outpost was cutting in and out.

After a few tense moments, Jaeger decided to mark the position and move back to our overlook position. After briefly considering a volley of 40mm grenades, the trio of Green Berets decided to just let the NMRG come out later for further inspection.

On the ride back, the music controversy continued, as if a potentially life-threatening situation had not just been averted.

“I don’t know, man,” Stoner lamented. “Sounds like hippie chick shit to me.”

The US Army Special Forces were established in 1952 under the command of former Office of Strategic Services (OSS) operator Colonel Aaron Bank. Although they were, and still are, a multifaceted organization with many capabilities, their bread and butter has always been unconventional warfare and foreign internal defense — not the sexy direct-action raids that Hollywood so often associates with them.

This is why SF soldiers must learn foreign languages as well as how to train and lead people who do not share the same culture or value systems as Americans. Green Berets are often the only American presence in an area (or even an entire country) and must be comfortable as equal parts warrior and diplomat — working by, through, and with indigenous and/or partner forces with little or no external support.

For Cotton, this means cooperating with Afghan commando and special forces units stationed in the area, militiamen with allegiances that shift sporadically, and area strong men who fancy themselves warlords. A local Pashtun man who considered himself a combination of the latter two, dressed in traditional clothing but with the addition of knock-off Air Jordans and a tactical vest, showed up for his weekly shura with the team sergeant at Blackfish’s front gate.

“Well, be lookin’ for me in a couple days,” Cotton told him, as the man pledged his help in the fight against ISIS. The man was concerned about his safety because of an alleged attempt on his life by the PUM a few days earlier and clearly wanted the protection of the ODA.

Cotton’s plan was to use the man’s militia as a potential plan B for their upcoming mission in the nearby Bagh Dara Valley — an area that was a stronghold for ISIS-K fighters. The Pashtun man was many things, but a coward was not one of them; he had proven his willingness to fight ISIS on many occasions. That alone was reason enough for Cotton to value their relationship with him.

Cotton attempted to reassure the man about his security situation. “I’ll go talk to the ANSF. If I hear something, I’ll let ya know.”

“I’m not lying about these guys,” the Pashtun militia leader insisted, despite Cotton’s assurances. “You can ask anyone about me, I will do the mission with you. But they call me infidel because I talk to the mentors.”

Many of the local Afghans refer to Special Forces soldiers as “mentors” because of their train-and-advise posture. The label isn’t inaccurate, although maybe implies a level of intimacy that’s not quite there.

Cotton, like many NCOs in the special operations community, delivered an entertaining form of no-nonsense conversation. He had no intention of sugarcoating anything with the Pashtun man.

“People have been callin’ me an infidel since I first came to Afghanistan in 2003,” he said. “I wouldn’t worry about it.”

After a few more passionate and very graphic oaths delivered by the Pashtun man to emphasize his allegiance to the ODA, Cotton stood, signifying his intention to end the Shura.

“Alright, we’ll be seein’ ya.”

Indeed, they would.

Able is frighteningly competent at his job. At any time of day or night, the young Air Force Combat Controller can be found sitting on top of the compound’s roof in his Crocs, T-shirt, and signature shades with a radio in hand — orchestrating mortar fire missions below and dropping bombs from F-16s above.

This deployment is likely his last hurrah as a controller though. Shortly after he returns to the United States, he will be starting a new career in finance — a passion that he has been studying for years in preparation. His transition will be the Air Force’s loss and Wall Street’s gain.

“Cleared hot,” Able delivered the line with the cool demeanor of a man who has given the greenlight more times than he could count. It’s the infamous confirmation that lets a pilot know he’s able to safely drop ordnance on the intended target. Moments later, the roar of jets filled the Mohmand Valley and a pair of black plumes appeared on a nearby ridgeline — the explosion’s report taking another second to reach us. Able explained that just before my arrival at Blackfish, he called in a similar strike that resulted in approximately 10 secondary and tertiary explosions — likely an ISIS weapons cache.

The mortar teams immediately began the carefully rehearsed choreography of hanging 120mm and 81mm mortar rounds, sending them deep into the same mountains that the bombs landed seconds earlier. All of this is what they call “terrain denial,” which is essentially incentivizing the enemy to stay off the high ground surrounding Blackfish. It’s a significantly more humane tactic than the old practice of planting landmines everywhere.

Security is a day in, day out offensive affair for the frontiersman of Mohmand Valley. Without reliable airpower, their numerically insignificant force would be at a dangerous disadvantage. But it does not replace boots on the ground. Patrols were regularly conducted up into the mountains above Blackfish, carefully cloverleafing the area for enemy fighting positions.

After the smoke from the bombs cleared, Jaeger led a formation of uplift troops out the front gates and immediately started ascending what they not-so-affectionately referred to as “PT Hill.” Stoner and Mark brought up the rear. The mission was to scout an area above the village where they hadn’t been before and look for cave systems and possible fighting positions.

The mid-afternoon hike eventually came to a halt; Jaeger spotted a few military-age males on the adjacent mountain, well within small arms range. The uplift troops took up security positions, and the trio of Special Forces soldiers moved behind cover with their “long guns” — rifles designed for long-range shots and fitted with special scopes. Many of the ODA’s members were also qualified snipers.

Further complicating matters, the uplift soldiers found a series of caves and fighting positions scattered in our exact location. Children’s laughter floating up from the village below could clearly be heard, offering an unsettling juxtaposition to the current status of the combat patrol. There were genuinely happy kids down there, despite the fact that they likely witnessed a beheading just a few weeks prior.

“ISIS-K is brutal,” Stoner explained in a whisper. “Half the time we listen to them, and the ’terps don’t even know where they’re from.”

He was referring to the radio signals they intercept from the enemy. Apparently many of the militants in the area don’t even speak languages found in Afghanistan, nevermind in Nangarhar province. Stoner went on to explain that many of them are literally mentally unstable. “They just want to rape sex slaves and murder people.”

After approximately 15 minutes of observation, it was determined that the Afghans did not pose a threat at this time. The patrol continued, snaking down a steep decline at a dizzying height. This is how many of the patrols went; not every excursion resulted in an exchange of gunfire. Maturity and patience must always outweigh the fear of the unknown in these situations; creating enemies of friends is not good for anyone.

We returned to Blackfish just in time for the brief about the next day’s mission in Bagh Dara — it was likely to get “pretty spicy,” as Cotton put it.

But if he was concerned about it, he didn’t show it. He switched topics and announced he was quitting his chewing tobacco habit — a more pressing issue. It wasn’t so much that he was quitting as it was that he had exhausted his supply, but fortunately someone had discovered pouches that the chaplain had delivered some time back. If Cotton were to lower his standards to pouches, it would surely result in his manhood being questioned — quite the conundrum. Nevertheless, he momentarily considered it.

Unsurprisingly, Doc Jeremy had a snide comment to make about the habit. As the team’s medical professional, he seemed to be against chewing tobacco altogether. Cotton picked up on it, “You talkin’ shit, doc?” It was a good-natured jab, but Jeremy didn’t back down: “Yeah, but you weren’t supposed to hear. I said you were weak — quit dippin’ for a day until more comes in the mail.”

Evoking a chuckle from the whole room, Cotton responded, “The point is that I quit …”

There was supposed to be a resupply flight coming that night though, so maybe the withdrawal would be short-lived.

“Americans have never come to this valley without taking fire,” Cotton delivered the sobering history of the Bagh Dara valley during the brief. “There’s likely 60 to 80 ISIS in there, so we’ll be linking up with the commandos at RON Darousey (the commando outpost at the mouth of the valley) but need to make sure they’re back by noon because of Ramadan.” The religious holiday put a strict timeline on the surveillance and observation mission, so the team would be departing Blackfish by 0500, he explained.

Although it was a very short distance away, the drive would still take an hour or longer because of the rough terrain, stream crossings, and narrow village streets that were not designed with American combat vehicles in mind. NMRG would lead the convoy up to the base of the mountain ridge overlooking Bagh Dara, where the team would then move on foot up the steep incline. The rigorous climb would be necessary to gain the high ground; Cotton emphasized the need for everyone to bring plenty of water.

“Americans have never come to this valley without taking fire.”

The meeting concluded, and dinner preparations began. The last of the personal pan pizzas had been eaten, much to the team’s chagrin. At least there was a resupply flight coming tonight.

Despite the early wake-up call for the mission, a movie was still in order. Tonight’s entertainment was Will Ferrell’s basketball comedy, “Semi-Pro.” Some of the Green Beret’s made last-minute preparations for the mission between bouts of laughter. Buck, in particular, was very focused on the Mk48 machine gun he had volunteered to carry. He was the only one carrying a fully automatic weapon on the mission and wanted to make sure everything was right. Even though the mission was to surveil and observe, he knew it wasn’t likely to go down like that — his heavy machine gun would probably need to be used.

The anticipated resupply flight never came that night.

The Mohmand Valley was black at 0430 the following morning, save for a few stars still lingering above. The valley boys of COP Blackfish slid on their kit, pulled their ball caps down tight, and conducted final radio checks. The light pre-mission small talk inherent to every military unit at war could be heard against the rumble of their military-issue gun trucks, already pre-positioned by the uplift troops that would be driving them.

American servicemembers are rarely allowed to leave their bases at this stage in the war; special operations troops who conduct train-and-advise, counter-terrorism, or counter-narcotics missions are the exception. This means that the shadowy world of special operations has essentially become the frontline main-effort of the Afghan war as it stands today — alongside their Afghan counterparts, of course. For the men of COP Blackfish, the mission into Bagh Dara Valley would be the latest iteration of that strategy.

This wasn’t their first excursion of the deployment though. They already had 19 missions under their belt and were responsible for approximately 47 enemy fighters killed in action. As of the publication of this story, that number has already increased.

The call was given to load up, and a few bolts slamming forward could be heard as the last soldiers racked a round of ammunition into the chamber of their rifles. Once they left the gate, anything could happen.

The NMRG humvees lead the convoy out of COP Blackfish as planned, the vehicles bumping violently as they crept along the unimproved roads. The night sky began to give way to pre-nautical twilight, so the few soldiers wearing night vision flipped their tubes up as the capability was no longer needed. Conversation was pointless over the roar of the engines, and everyone was preoccupied with pulling security anyway.

The drive exposed the Mohmand Valley and surrounding area for what it really is: beautiful. If it weren’t for the current state of the country, this valley would be an outdoorsman’s dream. Rushing streams, old stone buildings, green hills, and snow-capped mountains all come together in a canvas that no camera can truly capture. The blood routinely spilt and the horrors that are regularly perpetrated in this area is man’s greatest insult to the earth we occupy.

The convoy eventually arrived at RON Darousey, the Afghan commando outpost. This would be the last and only stop before reaching the base of the mountain the team would be climbing on foot, and so Able was performing his checks with the air cover alloted to the team that day. There was one problem: nobody was on their way.

Apparently, there was some confusion on what assets would be available when. This created a bit of a delay on an already tight schedule for the day. To make matters worse, the commandos informed Cotton that they would not be participating in the mission. This complication would put the ODA at a significant numerical disadvantage if the mission devolved to a force-on-force firefight.

The only option was to call the Pashtun militia leader that Cotton had met with the other day.

Within short order, Able had the air power lined up and ready to go, and Cotton had the militia en route. The new plan was to have the militia move in on the ground into the valley, while the ODA would climb to the ridgeline and coordinate air strikes in support of the militia if they took contact. Vehicles were reloaded, and the convoy departed the commando outpost for the short drive to the base of the mountain ridge.

After positioning the vehicles for a quick departure (just in case), the ODA started their ascent on foot. The terrain feature ahead looked significantly more intimidating at the base than it did from a distance. The climb was nearly straight up in some sections, and with the sun over the horizon, the heat began to play a factor as well.

The NMRG soldiers, not allowed to eat or drink from sunrise until sundown during Ramadan, lead the way with minesweepers. At one point, Buck turned around to warn me that I needed to step on stones only as these ridgelines were often littered with IEDs. Fortunately, we were able to avoid any that might have been there during our movement.

“Hey, we’re about 100 meters away, pass it back.” Buck’s directions came right after a short security halt to allow the NMRG to do their work and to be ready for anything that might kick off once the element crested the ridge.

I half expected the team to start taking fire as soon as their silhouettes became visible on the ridge, but the valley below was quiet. After closing the rest of the distance, quads on fire, the snipers began setting up in strategic positions, dialing in their “data on previous engagement” (DOPE). Able updated the aircraft that were loitering nearby, and Buck settled into a prone position behind his Mk48 machine gun.

All was still quiet 10 minutes after everyone had moved into their positions. I thought, Is this the calm before the storm? Cotton made an observation that maybe it would be a more simple surveillance mission than he anticipated.

Ultimately, an uneventful mission wasn’t in the cards this time. Moments later, the first explosion echoed from the valley and a series of small arms fire started rattling. Almost instantly, radio chatter started coming in from the Afghan element below, signaling that they were engaging pockets of ISIS fighters in the treeline.

“Hey, Cotton, am I good to airburst a bomb on that treeline?” Able had identified where the fire was coming from through his spotting scope and needed permission before dropping ordnance. Receiving confirmation from the team sergeant, he raised the F-16s over his radio, “Troops in contact … Bomb on target, one by GBU-54, air burst …”

A heavier machine gun started rattling, and a few more explosions were heard. It seemed that the small skirmish was escalating into a full-on firefight.

Cotton directed Buck to start firing his machine gun at the treeline, and he complied with gusto. The Mk48, a special operations variant of the M240B, is a fully automatic 7.62mm-caliber machine gun that is devastating even at long ranges — perfect for high-altitude firefights in Afghanistan. Buck’s three- to five-round bursts sometimes stretched into six to eight rounds, but the valley below was quickly turning into a target-rich environment. Before long, he needed to swap out his first 100-round ammo drum for a fresh one.

Able keyed his radio and said, “Cleared hot.” The roar of an American jet dropping in altitude could be heard in the distance. Simultaneously, the firefight in the valley below kicked up a notch of intensity with volleys of automatic fire going back and forth along with more explosions. The Afghan liaison with us from the militia calmly spoke into his radio, telling his comrades to get behind cover — a bomb was about to drop.

The 500-pound bomb dropped into the designated treeline with a sub-second flash of light before erupting into a black, four-fingered smoke plume.

Jaeger reported that they were taking effective fire. He responded in kind with multiple rounds of 40mm grenades from his M320 grenade launcher, thus earning his Combat Infantry Badge (CIB).

The firefight continued for nearly two hours. Cotton moved from position to position — under fire — expertly coordinating his team’s efforts while also returning fire himself. Able called in another airstrike, a 250-pound bomb this time, on a separate compound. RPGs left smoke plumes all over the hillside below. Buck came dangerously close to running out of ammunition because of how much suppression fire was needed. It became clear that the Bagh Dara Valley was every bit the ISIS stronghold that the team anticipated it to be.

Due to the Ramadan-induced time hack the team was under, they started to break contact at about 10:30 AM. Moments later, an IED exploded directly under our position, killing one of the Afghan militiamen as their element was moving out of the valley. A stack of white smoke floated into the air, denoting the spot where his life was lost.

Distraught calls for help came over the radio.

“They’re takin’ contact? Where?” Cotton yelled at the Afghan radioman. With all the gunfire and explosions echoing through the valley, it was difficult to tell what was coming from where. One thing became clear though: The longer the Green Berets stayed, the more deadly the situation would become. With up to 80 possible fighters in the valley, time was of the essence.

Cotton ordered Able to bring in the F-16s again, as well as the Apache helicopter gunships, and let them off the leash. Although the team was not in a position to come off the ridge and go down into the valley at this point, Cotton was not going to let ISIS get off easy. He and his men coordinated a furious volley of gunfire, the crack of their 7.62 long guns expertly “talking” back and forth with Buck’s Mk48 bursts.

After breaking contact, we started making our way back down to the vehicle rally point. Four F-16s and two AH-64 Apache gunships made pass after pass into the valley as we did so, firing 1,020 rounds from the 20mm cannons and 480 rounds from the 30mm cannons into the ISIS-occupied treelines and buildings. They were coming in so low and so frequently that we had empty brass falling on top of us.

Back down at the vehicles, the Pashtun man and some of his militia waited with their wounded. Cotton approached the distraught leader, still wearing his knock-off Air Jordans. He was doing his best to hold it together — the man who was killed was a friend of his — but emotions eventually gave way to tears. He made good on his promise to Cotton to show up when it counted.

Doc Jeremy patched up a wounded Afghan, and before long the team’s convoy departed for the ride back home. As we drove through the first village, local Afghans — routinely terrorized by the ISIS fighters in Bagh Dara — came out to show their gratitude to the soldiers. The Special Forces motto is De Oppresso Liber, latin for ‘‘to free the oppressed’’; the valley boys of COP Blackfish did their part to live up to that mission.

As the convoy crested the ridge back into Mohmand Valley, it was immediately apparent that a load of gravel the team had bought from a local company (and had been waiting for over 70 days to receive) had arrived while they were gone. It was already being distributed across the lot, transforming COP Blackfish from a tan-and-brown compound that blended in to the landscape to a distinctly gray feature that could be seen from quite a distance. The gravel would help keep down the amount of dust in the air during the dry season as well as prevent thick mud from forming during the wet season, but it was also a sign that Blackfish was here to stay.

If Cotton and the rest of his valley boys had anything to say about it, the Mohmand Valley would not be turning into the next caliphate headquarters for ISIS anytime soon.

All told, the first battle of Bagh Dara resulted in at least seven enemy combatants killed in action, one friendly killed in action, one friendly wounded in action, one enemy building destroyed, and multiple Green Berets earning their CIB. The mission of gaining an understanding of the actual enemy presence in the valley had been accomplished.

Back in the team’s common area, MREs were sliced open for dinner. Both jokes and analysis about the mission dominated the conversation. The nightly briefing was conducted as usual; more manual labor to improve the camp lay ahead, more terrain-denial fire missions, and more trees that needed to come down.

The resupply flight was pushed back once more; the team would need to go without personal pan pizzas and chewing tobacco for at least another day. Weather was the culprit, meaning Cotton’s contraption for controlling the flow of rain into his room would be tested yet again.

It’s the life of a Special Forces team, though. They live and fight in the most remote regions of the world, forced to make do with just enough to accomplish their mission. Their efforts in doing so are as formidable and persistent as the infamous ship Victoria, tasked with a mission nearly as ambitious in a world that expects them to fail — but for the most part doesn’t care enough to watch either way.

It doesn’t matter how long the war has been fought, what the politicians might say from day to day, or any of the other myriad issues that seem to dominate headlines in place of caring about the war they’re fighting. They are the men on the ground, and they worry about what they can directly control: taming the Mohmand Valley.

Jaeger flipped open the laptop and turned on the projector, as usual, for the night’s movie. Dark humor is usually the most appropriate dessert after a spat of combat; Quentin Tarantino’s “Hateful Eight” was a natural choice. A movie about frontiersman hampered by weather, wielding both diplomacy and violence — it was appropriate on many levels.

The room roared with laughter as Tarantino’s narrative masterpiece unfolded on the white sheet tacked to the wall.

“No one said this job was supposed to be easy!” said the hangman. Major Warren, played by Samuel L. Jackson, quickly replied, “Nobody said it’s supposed to be that hard, neither!”

At the request of NATO Special Operations Component Command – Afghanistan, all names of active duty special operations personnel were changed in order to maintain their personal security.

UPDATE: July 5, 2018. At the request of NATO Special Operations Component Command – Afghanistan, information identifying coalition nations has been changed.

Marty Skovlund Jr. was the executive editor of Coffee or Die. As a journalist, Marty has covered the Standing Rock protest in North Dakota, embedded with American special operation forces in Afghanistan, and broken stories about the first females to make it through infantry training and Ranger selection. He has also published two books, appeared as a co-host on History Channel’s JFK Declassified, and produced multiple award-winning independent films.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.