The Vietnam Combat Artist Program: The American Soldiers Who Documented War with Art

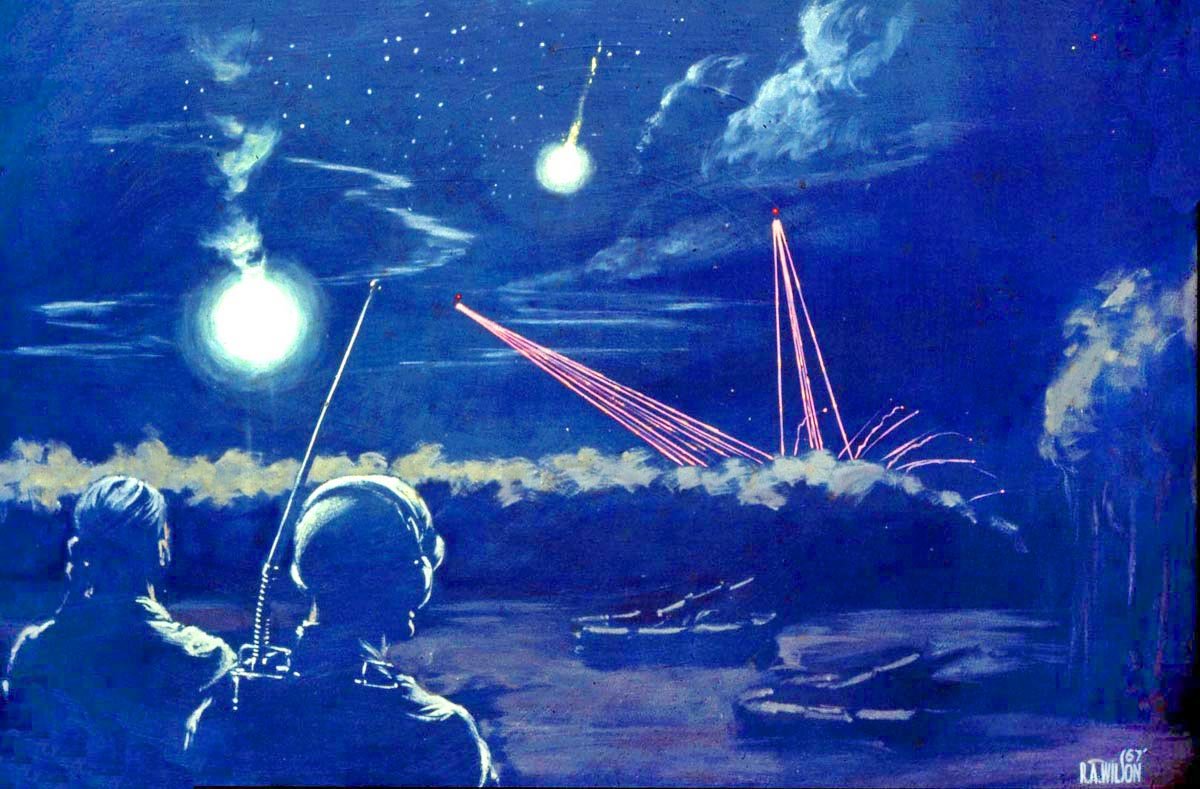

Ronald A. Wilson from CAT IV paints “SPOOKY” depicting American gunships attacking targets at night. Photo courtesy of SPOOKY by Ronald A. Wilson, CAT IV, 1967, Courtesy of the National Museum of the U.S. Army

Combat photographers, filmmakers, and war correspondents are responsible for capturing raw and intimate moments on the battlefield through images, videos, and the written word. Another interpretation of the war from the perspective of a soldier exists in the medium of creative expression.

The U.S. military used amateur and civilian artists to provide eyewitness works of art during the American Civil War, but starting with World War I, the U.S. Army officially commissioned artists to sketch, draw, and paint the activities of soldiers in frontline combat. A small team of eight artists from the Corps of Engineers had the difficult challenge of recreating warfare in Europe either by memory or during lulls in combat.

The Army Vietnam Combat Artist Program was established in 1966 and acted as a historical treasure trove for visual storytelling. “It’s different than a writer, a poet, or a photographer,” said James Pollock, a U.S. Army combat artist who was in the program. “It’s just another window into the history of a war.”

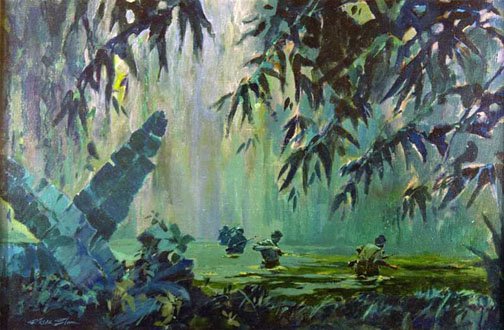

Pollock, a native of South Dakota, deployed to Vietnam as a member of Combat Art Team IV (CAT IV) in 1967. He and four other war artists — Samuel Alexander, Daniel Lopez, Burdell Moody, and Ronald Wilson — worked 24 hours a day drawing with great detail scenes of soldiers on patrol, doctors performing life-saving surgery, and GI’s playing card games.

Nine total CAT teams deployed to Vietnam from 1966 to 1970 on 60-day rotations. Some combat artists used cameras as a reference to what they were drawing or painting, which helped them when they left Vietnam and returned to Hawaii, where they finished their progress in art studios. Each work of art, whether it was in black-and-white or color, provided a broader impact of the emotional illustrations.

“The photography, I think, is a snapshot of time, of what is in front of you,” Pollack said. “And art is probably a snapshot of what is going on emotionally. You can extend your emotions. With photography the moment is there, and if you don’t get it, you’re not going to get it. But an artist can go in there, and if he misses the cue, he still experienced it, and he can come back to it, and come up with some kind of expression.”

Lopez had a series of 20 canvas paintings that covered his time spent as a war artist in Vietnam. “My series dealing with the Vietnam War propels the viewers to look into the abyss of their own souls and ask, ‘How can this happen?’ ‘How can I stop this human destruction?’ ‘How can I become a better human being?’” he wrote in the biography on his website.

Although the Army Vietnam Combat Artist Program ended in 1970, other branches have had their own respective programs throughout the wars and conflicts. Military and civilian artists remain active in combat zones around the globe and have also assisted in humanitarian operations. The U.S. Army’s art programs have archived artwork from World War I to present day. As of 2010, it contains more than 15,000 pieces of art.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.