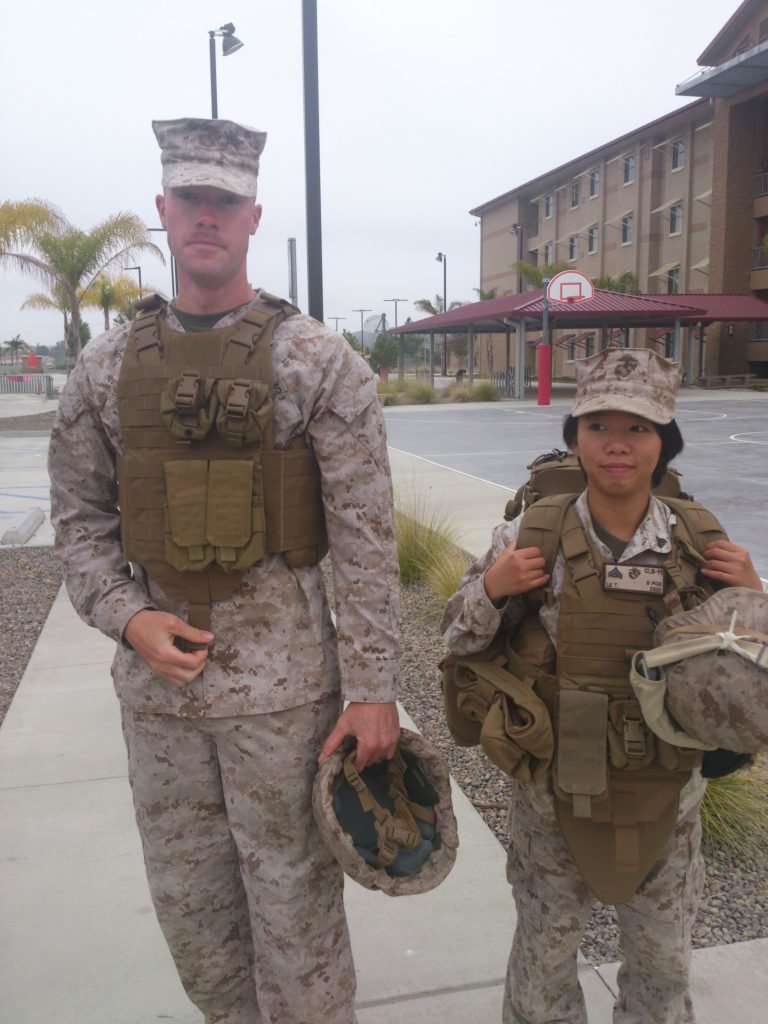

Photo courtesy of Tana Le.

Ho Chi Minh City, the most populated city in Vietnam, is a spiritual capital for those of Vietnamese descent. It is infamously the city where monk Thich Quang Duc set himself ablaze in 1963 to protest the persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government under Ngo Dinh Diem.

The city formerly known as Saigon was also a focal point in the Vietnam War. When it fell to North Vietnamese forces in 1975, it eventually led to the reunification of North and South Vietnam, ending the war.

It’s also the city that now-American citizen and US Marine veteran Tana Le once called home. Le moved to America with her parents as a teenager, landing in Philadelphia when she was 15 years old.

“Everything was just so big, it was such a culture shock,” she recalled while highlighting what it took for her family to get to America. “My dad had his own company and gave it up for my future. His business centered around recycling plastic and turning it into bags. In today’s world, my parents could have been rich with that business.”

“They taught me that I can make my own life,” she said. “I wouldn’t be here without them.”

Le is part of a burgeoning group of Vietnamese Americans in the United States military, including Gen. Viet Xuan Luong.

Luong was the first Vietnam-born person to achieve the rank of general in the US military. He was appointed command of the US Army Japan in 2018 and maintains responsibility for over 2,500 soldiers in and around Japan.

His story of American patriotism began during the siege of Saigon when he was 9 years old. Luong’s father was a Republic of Vietnam Marine Division major, and with the help of the American military and a reporter during Operation Frequent Wind, he and his family escaped to America as political refugees.

“It’s like, ‘OK, pack your stuff — do not talk to any of your friends, just pack some clothes,’ and his driver snuck us out at night,” Luong said during an interview with NPR.

It was on the trip to America that Luong decided he wanted to serve in the United States military.

“People might not believe that, but, I knew right back then that I want to serve our country,” he said.

Since then, Luong has had an illustrious military career fighting the Taliban in Iraq and Afghanistan, serving at Fort Hood, and now commanding the American soldiers in Japan.

Another Vietnamese American soldier who shot up the ranks is Huan Nguyen, who became the first Vietnamese American promoted to rear admiral in 2019.

Nguyen was born in Hue, Vietnam, the son of an officer in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. They lived outside Saigon, and it was during the Tet Offensive in 1968 that Nguyen’s mother, father, five brothers, and sister were killed by Viet Cong forces. During the attack Nguyen was also injured, taking a shot in the arm and the thigh, with another bullet piercing his skull. He survived, waiting with his mother until she died before escaping to his uncle’s home after nightfall.

“It was like going to war every day. I had to fight for them to treat me equally.”

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, he also escaped to America as a political refugee.

“I was one of those refugees, apprehensive about an uncertain future, yet feeling extremely grateful that I was here at all,” he recalled.

While Le’s journey to America was not as a refugee, she still faced many challenges, including the language barrier. She didn’t know how to speak English. She recalled, “I didn’t even know how to ask for directions.”

When Le entered high school, she took part in ESOL classes, English for Speakers of Other Languages. She had a translating machine to help her decipher conversations — until her aunt took it from her.

“My aunt took away my translating machine because she didn’t want me to use it as a crutch,” Le said. Instead her aunt gave her a simple Vietnamese-English dictionary to use and study. “I made sure to memorize a new word every day.”

But it was hardly an easy transition. Le laments her initial loneliness in America.

“I didn’t have anyone to really talk to, all the other kids in the house were so young,” she said, including her 8-year-old brother. Other than her parents, the other adults in the shared household — a combination of two immigrant families — spoke Chinese, not Vietnamese. At school, she had trouble making friends.

“I made friends with someone from Ukraine, Korea, China, and Cambodia,” she said. These friends were also in ESOL classes, and they all helped one another learn English a little better.

After about a year and a half in Philadelphia, the Le family moved to Boca Raton, Florida.

“I think [my dad] wanted to take care of the family on his own,” Le said.

While in Florida, she tested out of ESOL after two years in the program. Then she met a recruiter for the Marine Corps.

“I had just graduated high school and had no goal for college,” she said. “I saw it as my way to gain independence. Traditionally, women in Asian cultures are married and have children very young, and I knew that wasn’t for me.”

The only problem is that when she applied to join the Marines she stood on the wrong side of 5 feet — barely taller than the rifle she’d be carrying — and weighed around 90 pounds. The weight minimum to join the Marines at her height was 97 pounds, so she had to bulk up for the opportunity ahead of her.

“I was always the smallest person everywhere I went,” she said.

After clearing the weight requirement to enlist, Le soon faced other challenges, particularly with her size and gender.

“It was like going to war every day,” she said. “I had to fight for them to treat me equally.”

Le discovered that the general demands of military basic training were a lot for her, even though she was used to tackling challenges like starting high school in a new country and learning a new language.

“It was rough,” she said, but added that it made her stronger and more capable.

Basic training “definitely pushed me out of my comfort zone,” Le said. It also helped her form bonds with her fellow Marines and strengthened her understanding of American culture. Le served for nearly four years, leaving the Marine Corps in 2013 to attend Florida Atlantic University, where she earned a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in communication and media studies.

Vietnamese-born American service members such as Gen. Luong, Adm. Nguyen, and Tana Le are just a few examples who show that American patriotism isn’t always born in the United States — and that grit and determination can go a long way in reaching your goals. Even if you’re the smallest person in the room.

Tim Becker is a freelance journalist and journalism student at Florida Atlantic University. Tim has a diverse set of interests including gaming, technology, philosophy, politics, mental health, and much more. If he can find an angle to write about something, he will. Aside from his interests journalism is his passion. He wants to change the world with his words and photography. Tim writes for a variety of publications including the GoRiverwalk Magazine, the FAU University Press, and his personal blog on Medium.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.