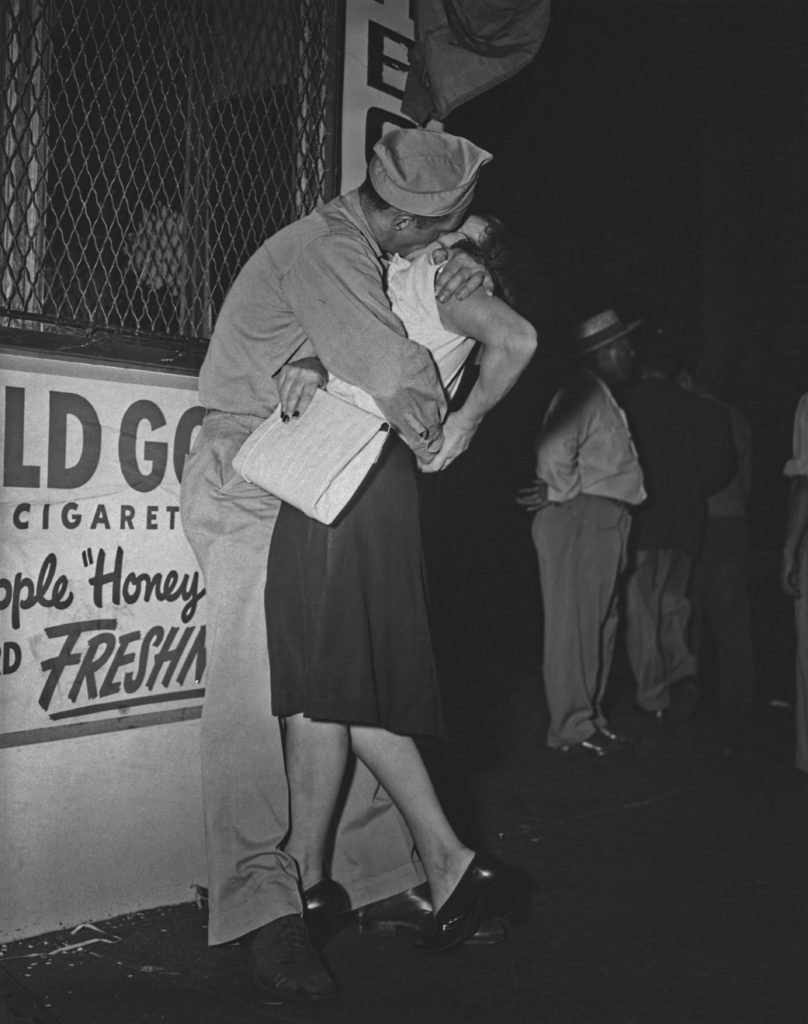

On Aug. 14, 1945, Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allied forces, marking the end of World War II (it was Aug. 15 in Japan due to the time difference). Known as V-J Day, or Victory over Japan Day, the surrender was secured after the United States’ brutal campaign in the Pacific, inching its way from island to island and ending with nuclear weapons being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

While August 14 is the day Japan actually surrendered, the ceremony and formal surrendering occurred on Sept. 2, 1945 — depending on who you ask, V-J Day is celebrated on one of these days.

As with any conflict, there are stories that slip through the cracks — lesser-known tales of courage and ingenuity that fascinate the few readers who stumble across them. Other stories were well-known at the time but are slowly being lost as the years tick by.

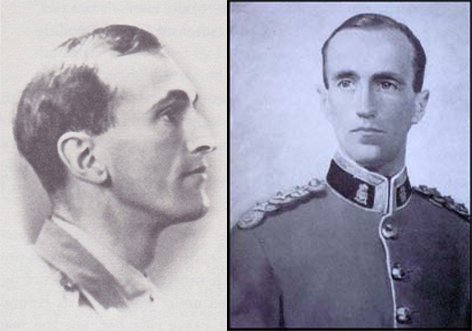

Grandfather Longlegs

It’s rare for a foreign soldier to become a hero in a foreign land — and rarer still for that person’s name to be passed down in local lore for generations. However, the name Hugh Seagrim is well-known throughout eastern Burma. Seagrim was a British officer known by many of the locals as Grandfather Longlegs for his tall stature; he was a quiet, religious man running military operations against the Japanese in a manner congruent with today’s Special Forces.

Seagrim worked alongside the Karen, a tribal group in eastern Burma that remains in the jungles today. He led a guerrilla campaign that was immensely successful, and he conducted it with very little help from Allied forces. The Burmese government had sided with the Axis powers, so not only were Seagrim and the Karen pitted against the Japanese, but also the local government. Like some of the other hilltribes, the Karen stayed on the side of the British and continued to fight.

Seagrim’s raids were effective, and as he trained and fought next to the Karen, the legends of his exploits grew. On one occasion, a bus full of Karen women wore extra-large skirts and hid Seagrim and several Karen riflemen underneath. They successfully carried out a modern-era Trojan horse raid. Another time they were ambushed, resulting in the death of a fellow British soldier, but Seagrim made it out. The entire campaign was rife with guerrilla tactics — small, precise attacks at key points to disrupt Japanese operations throughout Burma.

However, Seagrim’s campaign was so successful that the Japanese became acutely aware of his presence there, and they made specific efforts to stop him. They relentlessly hunted down his team of Karen, brutally torturing and murdering those they found. This was the fate for over 270 of them, but they remained loyal and would not turn in Seagrim.

The legend of Seagrim is rooted in his love for the Karen. The stories of his fighting prowess are as common as the stories of him enjoying life among the tribe. His affection for the people moved him to turn himself in to the Japanese to prevent further bloodshed on his behalf.

Eight Karen would not let him go alone, and they went to meet their fate by his side, though he asked that they remain home. All of them were executed together, and the campaign against him was successfully ended.

On one occasion, a bus full of Karen women wore extra-large skirts and hid Seagrim and several Karen riflemen underneath.

Seagrim was posthumously awarded the George Cross, the second highest medal for valor in the U.K.

Compelling as it is, there’s more to Hugh Seagrim’s story. His brother, Derek Seagrim, was also killed in action during World War II. In events in North Africa, completely unrelated to Hugh, Derek heroically led his troops (from the front) across a scaling ladder that he had put in place, and he took out two machine gun posts. There, he killed or captured an estimated 20 Germans. He died from his wounds but was awarded the Victoria Cross — England’s highest military honor.

They are the only two brothers in British history to have been awarded the Victoria Cross and the George Cross, both posthumously. This is the equivalent to two brothers being awarded the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Service Cross in the same conflict in different parts of the world.

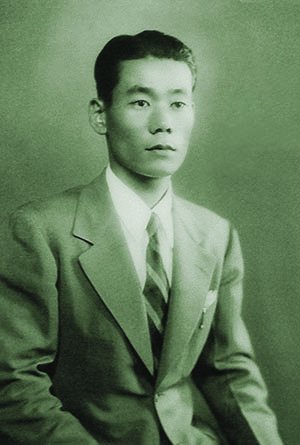

The Spy at Pearl Harbor

It’s 1945 and a man sits alone in the Japanese countryside. He’s dressed in the robes of a monk, and he appears to be a man of peace. As the American occupation of Japan ends, he opens a candy shop.

It would have been difficult to fathom that he was one of the primary Japanese agents on the ground in Hawaii in 1941. Takeo Yoshikawa’s efforts as an agent of Japan working covertly in the United States directly contributed to Japan’s effective surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Yoshikawa was living in Hawaii and renting an apartment that overlooked Pearl Harbor. From those windows and the surrounding areas, he was able to gather intelligence valuable for the impending attack — from ship sizes and types to force numbers, schedules, and movements.

Furthermore, he conducted espionage by diving in the area and renting planes for reconnaissance missions, all under the assumption that it would lead to an attack (though he was not aware of the specific attack). There were many Japanese living in the area at the time, so his presence was not suspicious.

When he heard the signal that an attack was imminent, Yoshikawa destroyed all evidence of his operations and left immediately. He was detained by the FBI, but was later traded in a prisoner exchange. They had no idea to what degree he was responsible for the death and destruction at Pearl Harbor.

In Japan, Yoshikawa lived in hiding, especially after the Americans won the war. In the 1950s, he finally came forward about his troubled past.

Was he lauded as a hero who did his duty, albeit on the wrong side of history? After all, despite fighting for the Nazis or Japanese empire, American and British soldiers have been known to at least admire specific acts of bravery and courage, even if conducted by the enemy.

Yoshikawa received no such accommodations. He was hated in the West, and when his history came to light in Japan, he was hated in his homeland, too. His name fell in line with the other architects of Pearl Harbor, and Yoshikawa was considered partially responsible for all of the subsequent casualties Japan faced — from service members to civilians.

Of the men and women who fought against the United States in America, Yoshikawa perhaps lost the most. Denied death in combat in service of his country, denied consideration for military medals or honors, and denied fame — the only thing he was granted was infamy. Yoshikawa died poor in a nursing home, a man hated in and by his own nation.

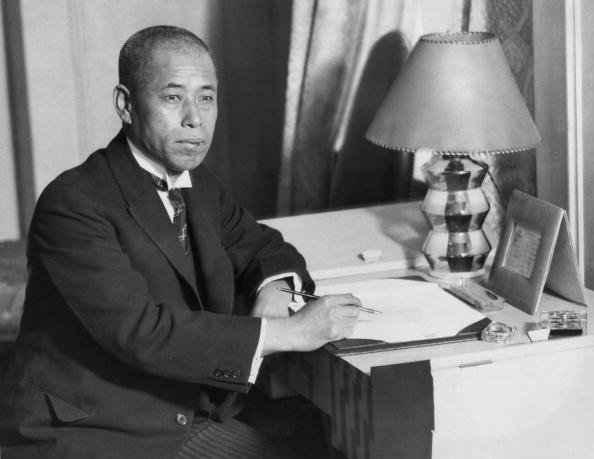

The Architect of Pearl Harbor and Operation Vengeance

Naval Marshal General Isoroku Yamamoto was one of the major Japanese military leaders in World War II. He is well-known as the overseer of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Battle of Midway, and countless other battles in the Pacific.

Yamamoto was killed as a result of Operation Vengeance, a concerted effort by the U.S. to track him down. This was not a single effort by a lone group; like most military operations, it was the result of a host of service members dedicating themselves to the mission. Finding Yamamoto would have been impossible without the work of the codebreakers of the U.S. Navy. They intercepted and deciphered a message that included the whereabouts of Yamamoto as he was traveling from island to island inspecting his campaign against the Americans.

1934: Portrait of Japanese admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (1884-1983), wearing a suit and tie, seated at a desk with a pen in his hand, London. Yamamoto planned and directed the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The assassination was successful. Though it has been heavily disputed as to who specifically shot him down, Yamamoto was killed over Papua New Guinea, which was confirmed the following day. Nineteen Japanese were killed in the two bombers that were shot down; one American pilot — Lieutenant Raymond K. Hine — was killed.

Attacks like these are not only strategically valuable, but they also boost morale for friendly forces and dampen enemy morale. To this effect, Operation Vengeance was a resounding success. The man who, in the public’s eye, was responsible for the attack on Pearl Harbor had seen retribution. Though the Japanese attempted to censor the gory details of his death, it was still a blow to lose such a significant leader.

This interception is well documented, but — surrounded by the countless other stories of gallantry and self-sacrifice by American service members in the Pacific — it threatens to fade with the fog of time.

Espionage and the world’s oldest profession

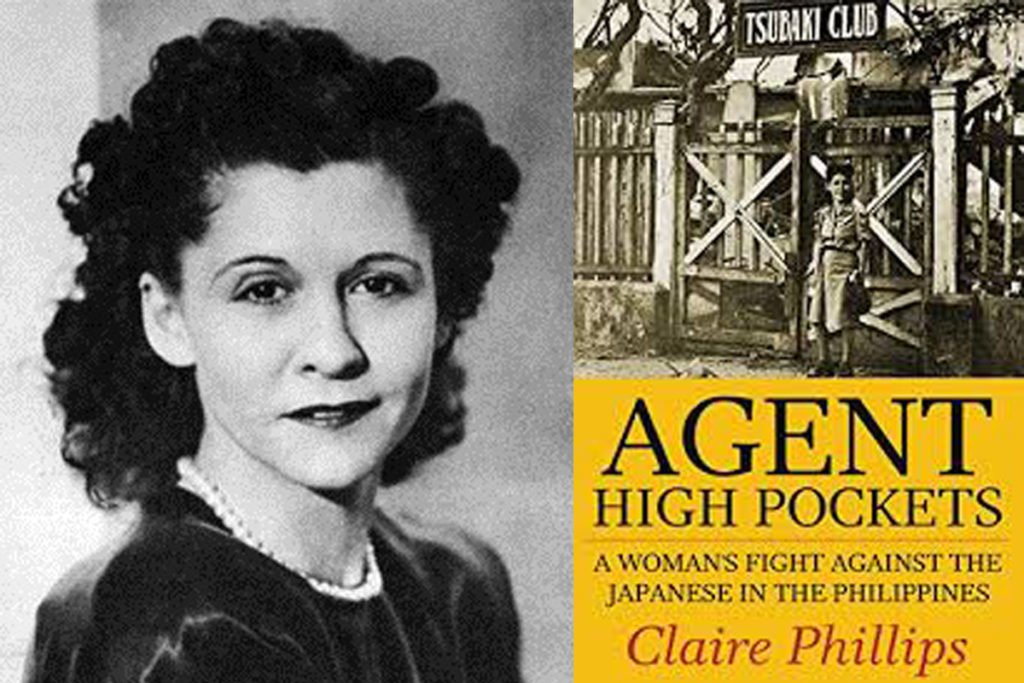

Claire Phillips was an American club owner in the Philippines prior to World War II. She met her husband, Sergeant John Phillips, an infantryman with the 31st Infantry Regiment, in Manila; they were marred in the jungle.

Phillips was later captured during the war. Though she was not aware at the time, he was killed in captivity, as with so many prisoners of war (POWs) captured by the Japanese.

Phillips did not leave when her husband was captured, and she did not flee alongside the droves of Americans exiting the Philippines as the war reared its ugly head. After she joined a group of insurgents, she started to use the profession she knew best to her advantage — the nightclub scene.

Her operation was not a half-baked plan; she forged a new identity and, from the ground up, built a gentlemen’s club alongside a Filipino dancer and friend. They called it Club Tsubaki, and it was located in Manila. It became a favorite for Japanese officers — it also became a central location for extracting information from military personnel.

When compared to how it’s portrayed on film, real-life spy work can seem quite boring on paper.

However, when it comes to Phillips, it was like something out of the movies. In his book “Ghost Soldiers,” Hampton Sides describes her as such: “[Phillips] dressed in a white evening gown with a plunging neckline and a slit halfway up her thigh …. Her olive skin would glitter with jewels.”

This was the environment they created. As with any social espionage, information wasn’t extracted by simply getting them drunk and asking obvious questions. The night’s debaucherous activities would be peppered by simple questions asked innocently. Questions such as “Where are you headed?” — and their answers — may seem innocuous on their own, but when combined with the answers of others, they begin to paint a picture of enemy movement and strategy.

In 1951, she was awarded the Medal of Freedom — an honor specifically designated for civilians who significantly aid in war efforts.

Phillips hailed from Portland, Oregon, and according to the Portland Monthly, “she was impulsive and addicted to drama. These qualities didn’t make her the greatest daughter, mother, or solid citizen. But they would make her an excellent spy.”

Despite her particular talents for espionage, Phillips was still captured and tortured by the Japanese. They had planned to execute her, but she was eventually sentenced to hard labor until 1945 when she was rescued by her American compatriots.

Phillips was later lauded for her actions — not only in the gentlemen’s club, but also her other efforts throughout the war, particularly smuggling essential medication, food, and other materials to POWs at Cabanatuan. In 1951, she was awarded the Medal of Freedom — an honor specifically designated for civilians who significantly aid in war efforts.

Luke Ryan is the author of two books of war poetry: The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence. Luke grew up overseas in Pakistan and Thailand, the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and conducted four deployments to Afghanistan, leaving as a team leader. He has published over 600 written works on a variety of platforms, including the New York Times.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.