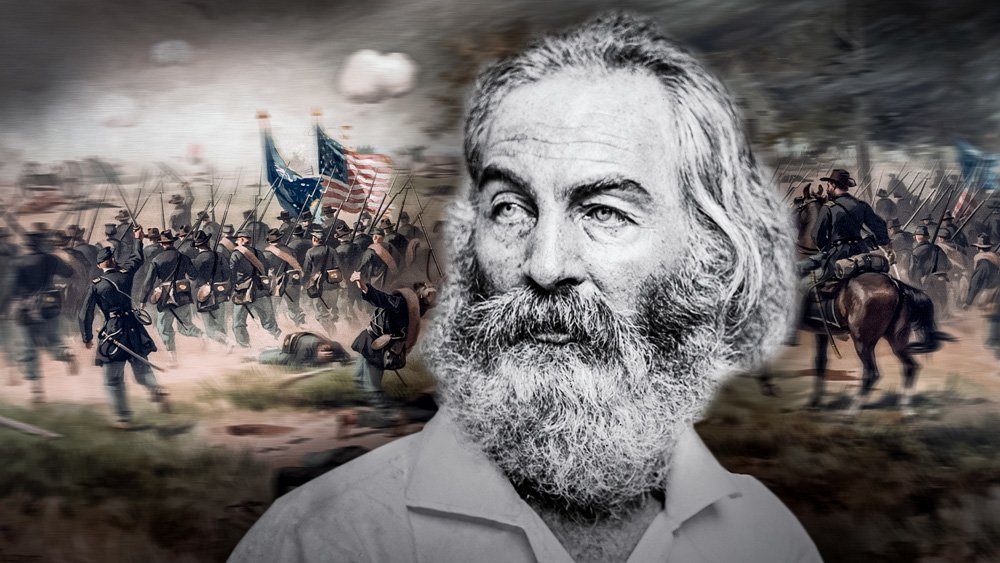

While Walt Whitman is best known for his transcendental "Leave of Grass," he also wrote powerful war poetry inspired by his time as a volunteer nurse during the Civil War. Composite by Luke Ryan, sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

Walt Whitman, a classic American poet known for poems like “O Captain! My Captain!” and “Song of Myself,” had a unique ability to marry lofty, romantic ideas with the reality of life down in the dirt. He celebrated the United States by celebrating the mechanics, carpenters, and masons. He also mourned the unfair reality we all live in by describing a baby bird abandoned by its mother.

Whitman served as a volunteer nurse during the American Civil War. This wasn’t just a brief tourist trip in and out of a war zone in order to influence his writing; reports say he treated thousands of patients during his service. Through his poetry, and thanks to his firsthand experience, he paints a picture of the war — from the inside of a hospital to the large battles and troop movements across the country.

Reading about the war through the medium of an established poet is a different way to look at impactful historic events. While poetry doesn’t give you a clear narrative of what happened and when, it shines a much clearer light on what it felt like to be on the ground in a way that a textbook cannot. A perfect example is the grit and sorrow communicated in “The Wound-Dresser,” where Whitman recounts treating young soldiers in an army hospital.

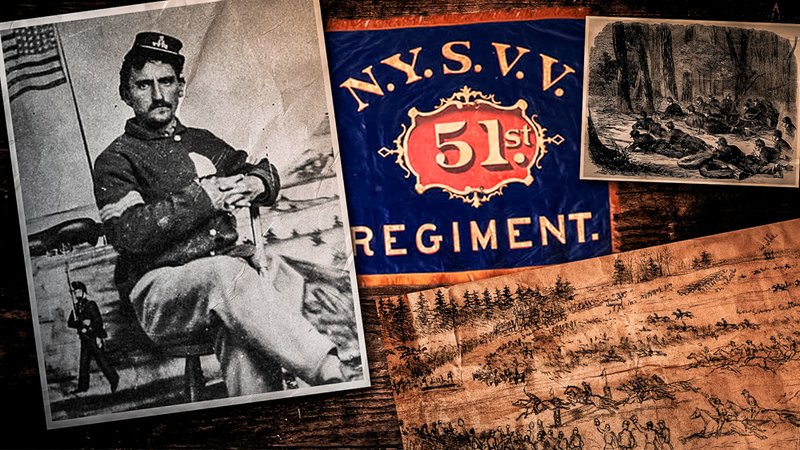

Whitman’s brother, George, left, fought in the 51st New York Infantry Regiment. At one point, Whitman thought George was severely wounded and traveled a great distance to see him — only to find his brother had a minor wound on his cheek. Composite by Luke Ryan, photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Bearing the bandages, water and sponge,

Straight and swift to my wounded I go,

Where they lie on the ground after the battle brought in,

Where their priceless blood reddens the grass, the ground,

Or to the rows of the hospital tent, or under the roof’d hospital,

To the long rows of cots up and down each side I return,

To each and all one after another I draw near, not one do I miss,

An attendant follows holding a tray, he carries a refuse pail,

Soon to be fill’d with clotted rags and blood, emptied, and fill’d again.

I onward go, I stop,

With hinged knees and steady hand to dress wounds,

I am firm with each, the pangs are sharp yet unavoidable,

One turns to me his appealing eyes—poor boy! I never knew you,

Yet I think I could not refuse this moment to die for you, if that would save you.

The poem alternates between the harsh realities of treating wounded trauma patients (packing bullet wounds, cleaning gangrene, changing dressings on amputated limbs) and the sorrow of the war around him:

I sit by the restless all the dark night, some are so young,

Some suffer so much, I recall the experience sweet and sad …

Veterans of all sorts of wars will be familiar with this duality — the visceral sweat, blood, and dirt that exists alongside cerebral thoughts of grief, courage, hope, and despair.

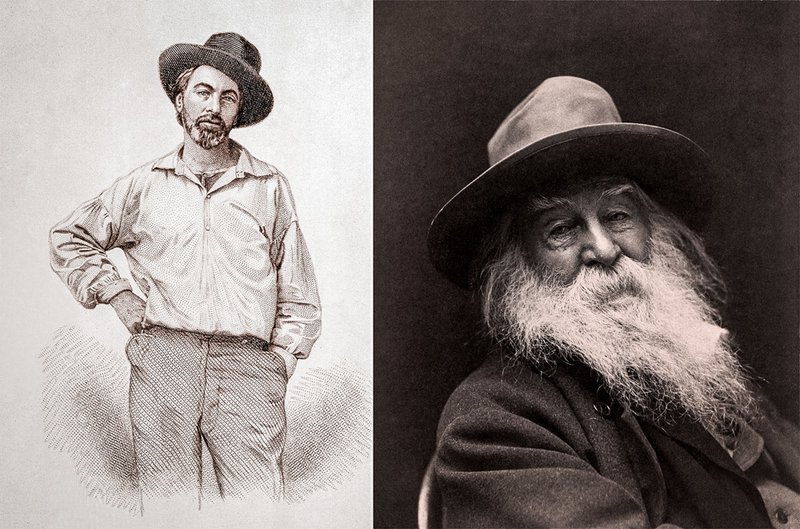

Walt Whitman in 1854, left, and 1887. Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Beyond his medical experience in hospitals, Whitman also witnessed the war unfold on a larger scale — a brigade moving through Brooklyn, stumbling across an unknown soldier’s grave in the woods in Virginia — history was unfolding in his backyard. He paints an almost-apocalyptic picture of conflict infecting his own home in “Eighteen Sixty-One”:

Arm'd year—year of the struggle,

No dainty rhymes or sentimental love verses for you terrible year,

Not you as some pale poetling seated at a desk lisping cadenzas piano,

But as a strong man erect, clothed in blue clothes, advancing, carrying a rifle on your shoulder,

With well-gristled body and sunburnt face and hands, with a knife in the belt at your side,

As I heard you shouting loud, your sonorous voice ringing across the continent,

Your masculine voice O year, as rising amid the great cities,

Amid the men of Manhattan I saw you as one of the workmen, the dwellers in Manhattan,

Or with large steps crossing the prairies out of Illinois and Indiana,

Rapidly crossing the West with springy gait and descending the Alleghanies,

Or down from the great lakes or in Pennsylvania, or on deck along the Ohio river,

Or southward along the Tennessee or Cumberland rivers, or at Chattanooga on the mountain top,

Saw I your gait and saw I your sinewy limbs clothed in blue, bearing weapons, robust year,

Heard your determin'd voice launch'd forth again and again,

Year that suddenly sang by the mouths of the round-lipp'd cannon,

I repeat you, hurrying, crashing, sad, distracted year.

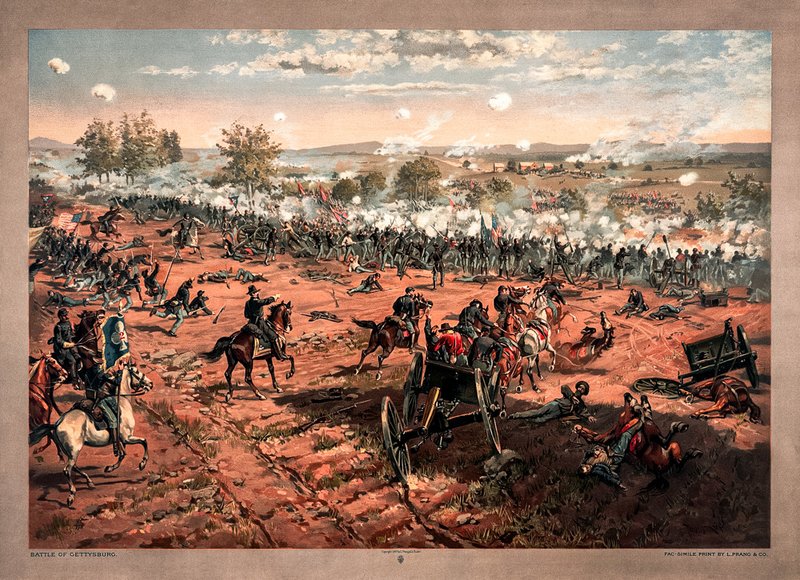

The Civil War cost more American lives than World War I and World War II combined. “Battle of Gettysburg” image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Whitman also tackles the generational burden of war. Many young men yearn for the chance to leap into battle, and they later become old men lamenting the sheer waste of it all. Few poems illustrate this reality more clearly than “The Centenarian’s Story,” in which Whitman describes himself standing next to a veteran of the American Revolution. The revolution was almost 80 years prior to the Civil War, so the veteran would have been quite old. The two are watching from a hilltop as young soldiers in the town below celebrate before heading off to war against the South.

Why what comes over you now old man?

Why do you tremble and clutch my hand so convulsively?

The troops are but drilling, they are yet surrounded with smiles.

Around them at hand the well-drest friends and the women

The old veteran goes on to tell Whitman that he fought on the very hill they just climbed. He recounts the Revolutionary War like it was yesterday:

As I talk I remember all, I remember the Declaration,

It was read here, the whole army paraded, it was read to us here

The veteran of the revolution reminds Whitman:

Who do you think that was marching steadily sternly confronting death?

It was the brigade of the youngest men, two thousand strong,

Raised in Virginia and Maryland

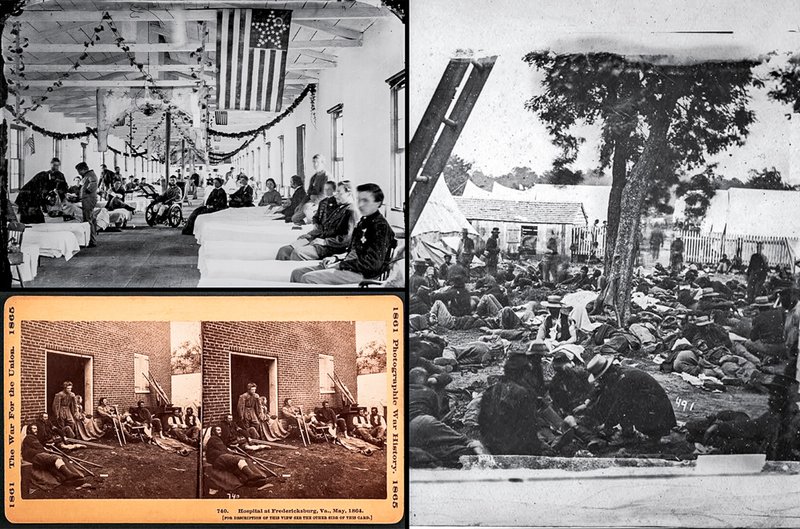

Hospitals came in all shapes and sizes during the Civil War. These are the environments in which Walt Whitman worked. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress.

He goes on to describe the battle in detail — and the unfathomable loss it incurred.

By the end of “The Centenarian’s Story,” we look down the hilltop through a new lens at this restless generation of young men eager to fight a war in their homeland.

It’s one thing to write about war as an outside observer; it’s another thing to write about it from first-hand experience. Through Whitman, we have the rare opportunity to hear about the Civil War from an emotional perspective. These poetic observations are an essential part of American history.

For more of Whitman’s war poetry, read the collection Drum-Taps.

All poems included in this article are in the public domain.

Read Next: Marine Veteran Ben Fortier Parses the Nuances of Combat in a New Book

Luke is the author of two war poetry books, The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence, and a post-apocalyptic novel, The First Marauder. He grew up in Pakistan and Thailand as the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and deployed to Afghanistan on four combat deployments. Now he owns and operates Four Hawk Media, a social media-focused marketing company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.