Verses Born in Battle: A Comparison of World War I and GWOT War Poetry

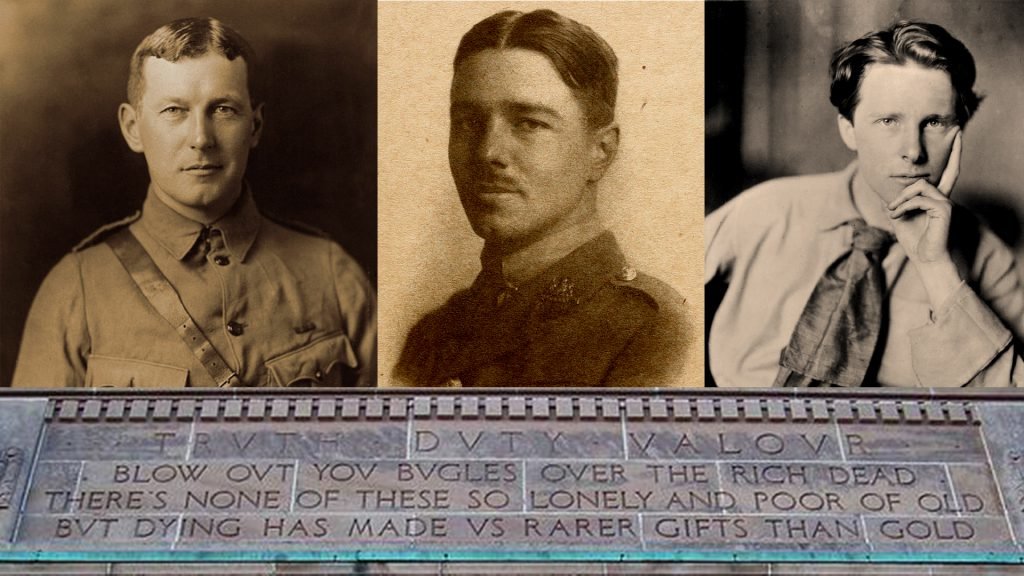

war poetry. Composite by Luke Ryan/Coffee or Die Magazine.

War poetry: the coupling of words seems like a contradiction. How can poetry be fashioned out of so much disarray? How can something creative come out of the most destructive state human beings are capable of?

While poetry is often associated with romantic love, some of history’s most moving and popular poems have come out of the infernos of war. A whole slew of poetry was born from the trenches of World War I, where poets like Rupert Brooke and John McCrae wrote words that still circulate today.

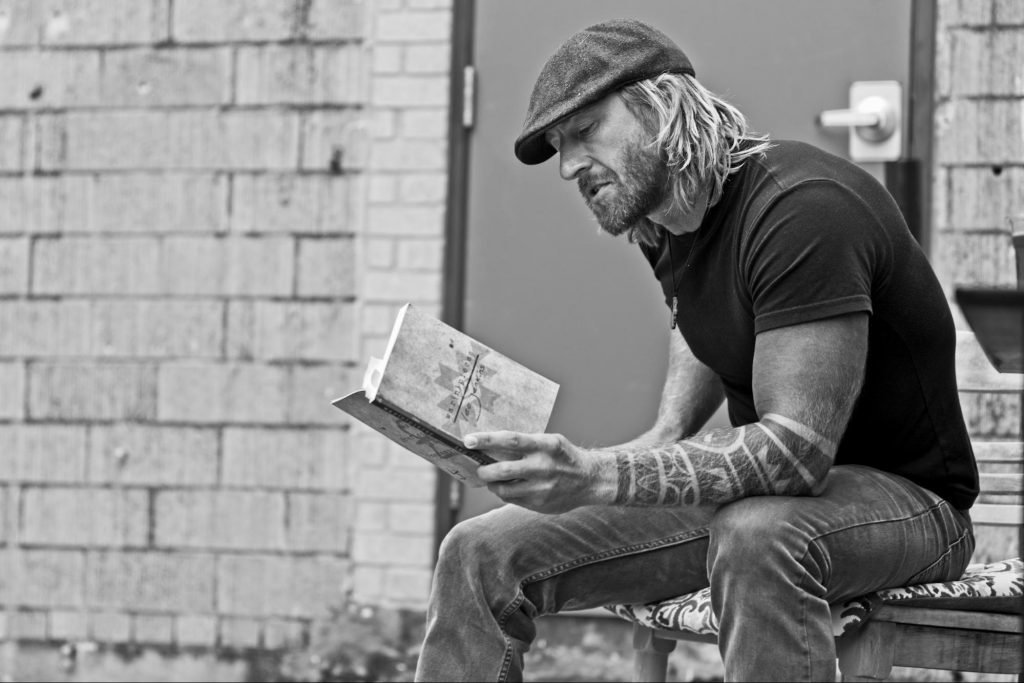

Poets are not exactly common in today’s warrior circles, but they do exist. In fact, they have been making something of a resurgence in the last 10 years as the United States has continued on with the Global War on Terror. As men and women of the armed forces are continuously put in harm’s way, a growing few have found solace in understanding their experiences through the medium of poetry.

The similarities in modern war poetry and war poetry of World War I are striking, and they speak to the transcendent nature of war. Despite the changes in technology, the difference in scope of conflict, and difference in nationalities — some things never change.

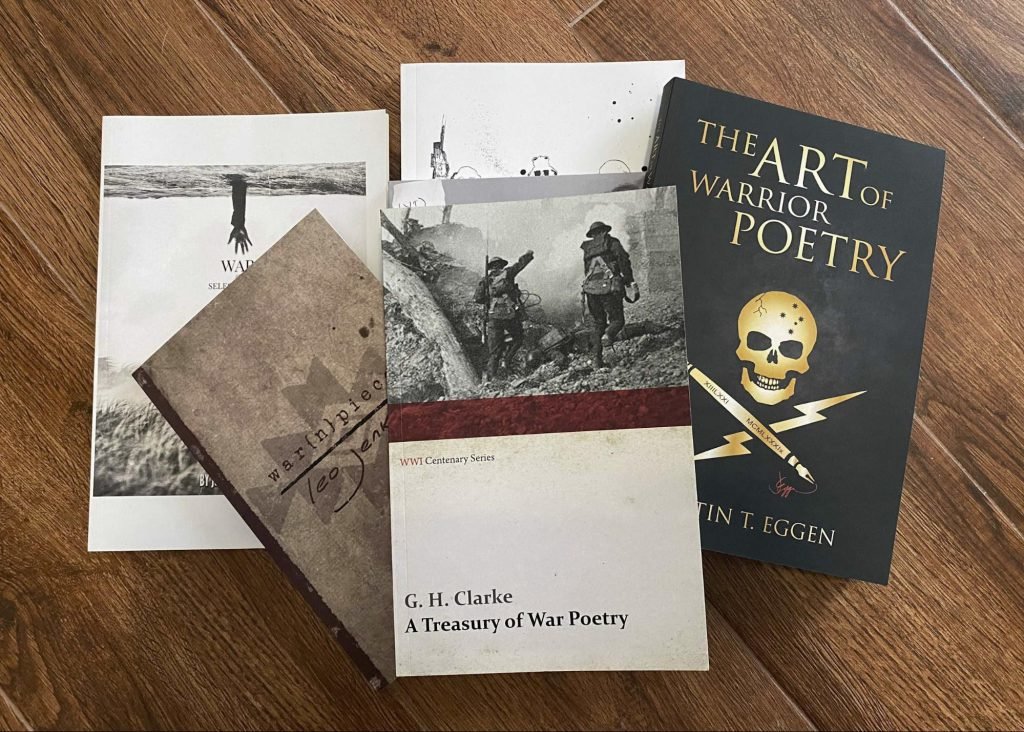

Before comparing poetry between World War I and the GWOT, it’s important to mention the differences between the wars. In Leo Jenkins’ poem “war{n}pieces,” from the book of the same title, Jenkins describes his journey after a history of human conflict in an incredibly profound poem.

There are pieces of me

I’ve kept unseen;

Frayed and crumbling.

Shy – hiding behind

A thin veil of serenity.

They’re not agony,

Nor world ending,

Or a soul torn in two.

They’re heavy, that’s true.

But they’re nothing new.

This poem was written years after Jenkins’ experiences in war. Sadly, if one is to Google search the war poets of World War I, the range of dates for the poets’ lives will tell a whole story of its own — the dates tend to end somewhere between 1914 and 1918. Many of them never got a life after the Great War to reflect upon their experiences. The GWOT has seen its fair share of men and women killed in action, but the difference between them is worth mentioning.

Still, the parallels between poets like Jenkins and poets like Wilfred Owen are striking.

The Tools of War

“The Kiss” by Siegfried Sassoon

To these I turn, in these I trust;

Brother Lead and Sister Steel.

To his blind power I make appeal;

I guard her beauty clean from rust.

He spins and burns and loves the air,

And splits a skull to win my praise;

But up the nobly marching days

She glitters naked, cold and fair.

Sweet Sister, grant your soldier this;

That in good fury he may feel

The body where he sets his heel

Quail from your downward darting kiss.

An excerpt from “Put Down Your Steel” by Cokie

“I awoke in the GWOT with tattoos, dip, and gun.

Rifle and pistol, radio and bombs

were irreverent tools of my deadly trade.

My list of enemies grown vast and diverse,

global foes both worthy and not.

As I slumber in sand I hear the near voice;

“Put down your steel, old warrior,

for is the life left to live!”

“I cannot,”

I whisper tearless and cold, desp’rate to survive.

“My rifle is here to stay.

Without it, I am nothing,

I know no other way.”

There is a lot to unpack in both of these poems, with themes that intersect and others that are unique to the writer. There are a few conspicuous similarities that can be found all over centuries of war poetry: the very practical focus on the tools of war and the recurrent use of the word “steel.”

War is not a romantic, ethereal space where forces of good and evil obscurely swirl around one another. It’s quite the opposite; it’s a vivid reminder of the physicality of life, and in a war the direct connection to that physicality is seen through its weapons. Swords, rifles, grenades, bows, tanks, flamethrowers — they are described differently in every poem, but they are very often the focus of the poet. This is the thing that they trained with and that they held in their hands when almost every deed of combat was conducted.

The feelings in both poems are complicated. One personifies the weapon, the other displays a dependency upon it. In both, the weapon is a symbol of destruction and protection, and its value is clearly of utmost importance. After all, it’s the same kind of tool that could cause the poets’ own demise, and yet that may allow them to leave with their lives and to protect the friends to their shoulder.

Empathy for the Enemy

“German Prisoners” by Joseph Lee

When first I saw you in the curious street,

Like some platoon of soldier ghosts in grey,

My mad impulse was all to smite and slay,

To spit upon you — tread you ’neath my feet.

But when I saw how each sad soul did greet

My gaze with no sign of defiant frown,

How from tired eyes looked spirits broken down,

How each face showed the pale flag of defeat,

And doubt, despair, and disillusionment,

And how were grievous wounds on many a head,

And on your garb red-faced was other red;

And how you stooped as men whose strength was spent,

I knew that we had suffered each as other,

And could have grasped your hand and cried, ‘My brother!’

“In This Place” by John Daily, from War… &After: The Anthology of Poet Warriors

In another place you’d be in school or on your way.

In another place you’d be thinking of girls, or cars, or sports.

In another place it would be a baseball bat or a fishing pole over your shoulder.

In this place it’s an AK, and you’re a “Military Aged Male.”

In this place, through my scope, I can see both fear and resolution in your eyes.

I pray you get to be a kid in the next place.

The battlefield is certainly a place teeming with dichotomies. There are plenty of stories about how soldiers grow to hate the enemy — those nameless, faceless beings who maim and kill their friends. That hatred is often encouraged, seen by some as fuel for the fire that will push a soldier to take a trench or storm a building.

However, the thing about the front lines is that, at some point, the two will actually come head-to-head. This is illustrated in the character Paul Bäumer in All Quiet on the Western Front, who stabs a soldier to death and is forced to confront his fallen adversary’s humanity as he is stuck in a crater with the corpse for an extended period of time. It’s also illustrated in war poems across the last century, like the two above.

War is simply human beings locked in mortal conflict with other human beings on a large scale. By definitions, those human beings will collide and when they do, they will be forced to look one another in the eye. This was the case 100 years ago, and it’s the case still today.

Warrior Souls

An excerpt from “Mama Knew I Was Gonna Be a Warrior” by Justin T. Eggen

Mama knew I was gonna be a Warrior but didn’t know there was gonna be a war –

on a fateful day in September the towers crumbled to the floor

Military mobilized and troops were sent to battle-

mamas biggest fear had occurred- she was shaken and rattled

for she knew her boy wanted to matter.

An excerpt from “To a Soldier in Hospital” by Winifred M. Letts

Courage came to you with your boyhood’s grace

Of ardent life and limb.

Each day new dangers steeled you to the test,

To ride, to climb, to swim.

Your hot blood taught you carelessness of death

With every breath.

So when you went to play another game

You could not but be brave:

An Empire’s team, a rougher football field,

The end—perhaps your grave.

What matter? On the winning of a goal

You staked your soul.

As the names imply, the world wars saw the whole world in a state of war. That meant everyone, and the drafts made it so scores of people who wouldn’t have been soldiers otherwise had to serve in combat.

However, some are warrior souls from a young age. Both of these poems capture a sense of that warrior spirit that starts from youth and carries on into battle. Even for those who didn’t fancy a career in the military as a boy, combat has a way of making the combatants feel like every step of their life has led up to that point. This is because whatever you’re doing in a firefight is the most important task of your life for those moments of fire and brimstone.

That fixation on youth is seen in a lot of poetry, new and old. Be it a loss of youth, a longing for the simplicity of childhood, the comparison made to soldiers and children (since so many of them are so young still), or the contrast of a young soldier with old eyes — these themes abound.

There are scores of other parallels to be had between generations of poetry, and many of them go far beyond the last century. Walt Whitman was a volunteer nurse in the Civil War, and with some adaptation to the language it would be easy to think some of his poetry was written from some battlefield hospital today. The Iliad is filled with themes of the temporal nature of life, seen most clearly in a time of war. Indeed, the oldest book known to man, Gilgamesh, speaks of the grief of a lost brother in a way that still feels raw today.

And all of these themes can be found in war poetry written in the last few years.

Luke is the author of two war poetry books, The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence, and a post-apocalyptic novel, The First Marauder. He grew up in Pakistan and Thailand as the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and deployed to Afghanistan on four combat deployments. Now he owns and operates Four Hawk Media, a social media-focused marketing company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.