Composite by Kenna Milaski/Coffee or Die Magazine.

On my second deployment to Afghanistan, the base Morale, Welfare and Recreation facility, which consisted of a few computers with an internet connection, allowed open (though monitored) communication with loved ones back home. We had a lot of leisurely advantages over deployed soldiers throughout history, but the ability to email family on a dime easily ranked among the highest.

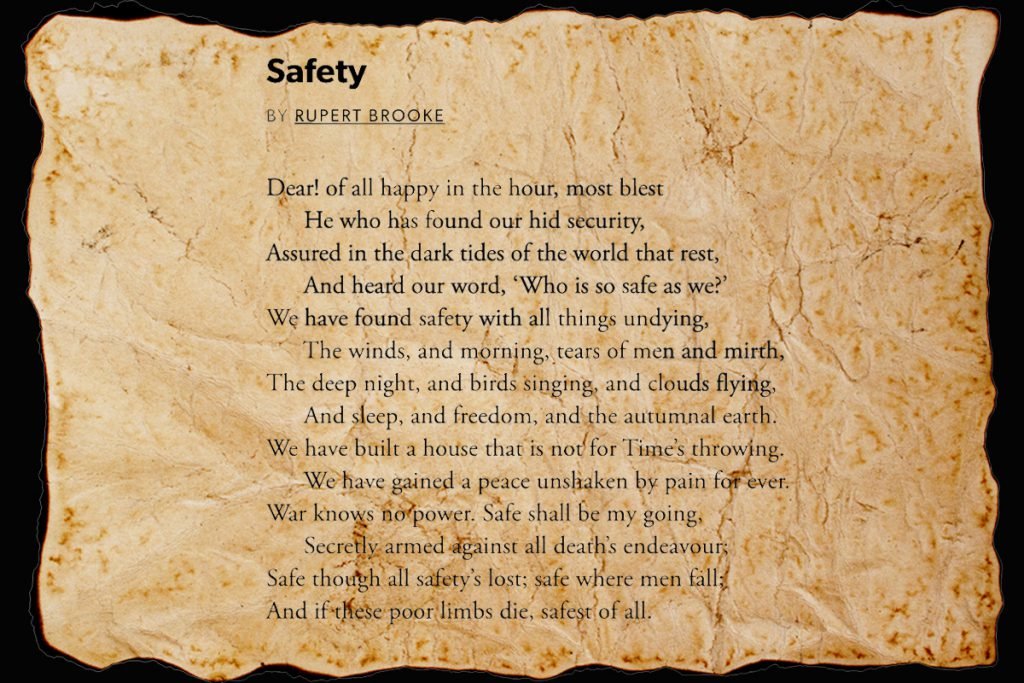

Sitting in the facility, I clicked open an email from my father. Its contents were little more than a single poem without context:

The more I read it, the more it meant to me.

As a member of 3rd Ranger Battalion, I was constantly stressed out. I worried about measuring up to my peers, about my performance, and about the health and welfare of my men. But I also always felt this deep notion of safety, and I wasn’t sure why. This 100-year-old poem appeared to have the answer.

Like many warriors throughout the ages, I had been forced to root my sense of security in all things “undying,” since you can’t rely on the safety of the flesh in a firefight. This sense of safety in things undying was particularly apparent in things like nature, which have inherent value in the moment you experience them. When you’re sitting on the back of an MH-47, watching beautiful and ancient mountains roll by, there is value in that moment that cannot be taken away. When you’re back home, sitting on your porch and sharing a beer with your friends in the crisp night air with the crickets chirping — the minutes can expire, but time cannot rob you of them as they are happening.

We have a tendency to focus on the ending of such things, but just as the terrible moments always return, so do the beautiful ones. They have inherent value as they occur. The biggest one for me was the brotherhood with my fellow Rangers. Death would have no effect on that; in fact, it would only make it stronger.

As such, “War knows no power. Safe shall be my going.”

I printed that poem out and carried it through the rest of that deployment and each one thereafter.

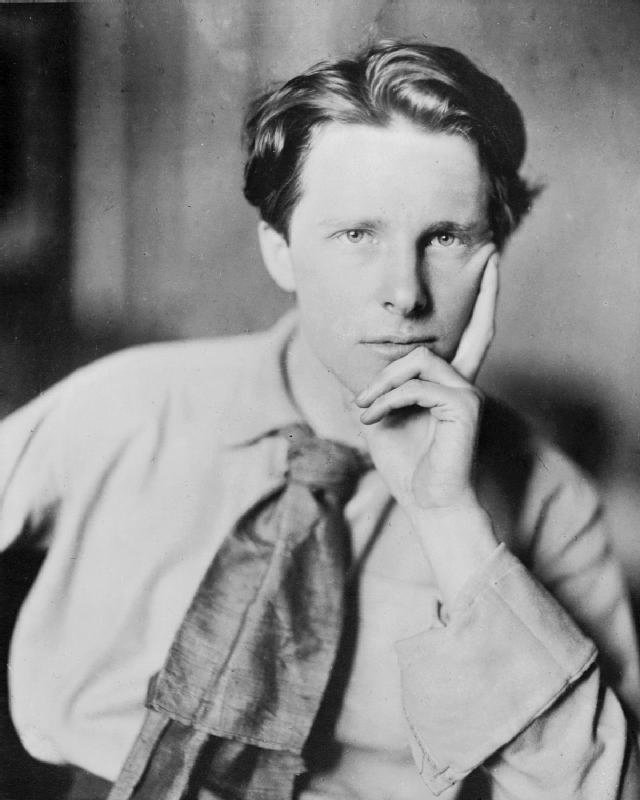

I knew the poem was written in 1914, in the throes of World War I, but I didn’t know much else about Rupert Brooke beyond that. My thirst to expand my literary knowledge had only just begun, but I started to dig. I discovered that Brooke volunteered to fight in the war, commissioning in the Royal Naval Division. As a part of the British Expeditionary Force in a world war, he was no stranger to violence.

Rupert Brooke died of sepsis at 27 — on William Shakespeare’s birthday, no less. I had seen my friends torn up, and I had seen them suffer at the mercy of mother nature as well — certainly not to the extent of a world war but enough to be able to extend my imagination to Brooke’s situation. His illness was the result of an infected mosquito bite on his lip, but like the countless people who died in similar, seemingly senseless ways at the time, his death was undoubtedly a result of the war.

It’s strange, connecting so strongly with someone who died so long ago, but it drove me to read more. The Dead and The Soldier were two first choices, though none hit me quite so hard as Safety. Lines like “We have gained a peace unshaken by pain for ever” evoked either something I had achieved that reverberated with my soul, or a dream I was desperately chasing. I wasn’t sure which, but those words struck a chord. They still do.

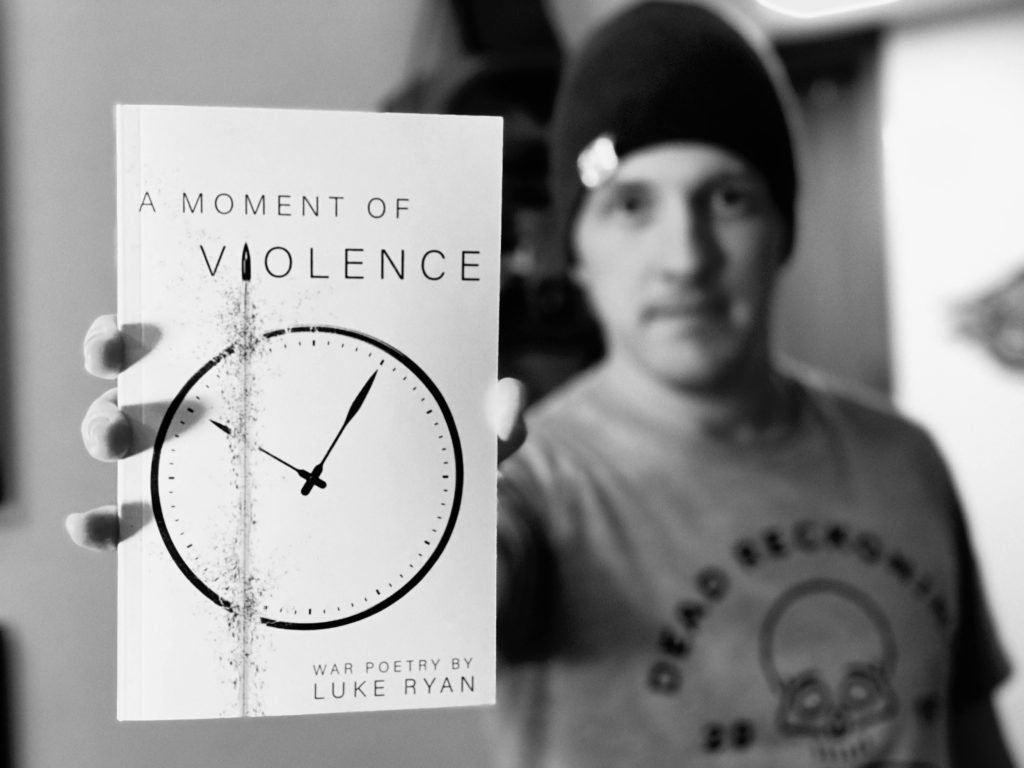

Coincidentally, I was 27 when I felt the urge to write poetry about war, in an attempt to understand the facets of my experiences that were too difficult to put into simple, descriptive words. I’ve never been under any impressions that my poetry would even remotely measure up to Brooke’s, but on a personal level, I always felt a deep kinship to his work and wanted to make some of my own.

It is a great gift to write something and realize others are moved when they read it. It’s another thing entirely to have inspired other people to action, simply by the power of your pen. And that is something else Brooke has achieved — a safety of sorts in his own words. Years after his death, they continue to inspire others to act, to write, to create — even after some very dark moments.

Brooke found a security in battle, despite the severe danger around him on a daily basis. I had that too once. But there are still things in which we can find that safety — those precious moments that you can live in if you choose, which have value in the moment they exist. That kiss with someone you love, holding the hand of a newborn child, or finding that conversation with a rare friend who truly understands you to your bones.

Brooke’s poetry inspired me during the war, yes, but the inspiration has extended long beyond that. Every day I remind myself to find those things — the things that are not for time’s shaking — to find them and to live in them as they happen.

Luke is the author of two war poetry books, The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence, and a post-apocalyptic novel, The First Marauder. He grew up in Pakistan and Thailand as the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and deployed to Afghanistan on four combat deployments. Now he owns and operates Four Hawk Media, a social media-focused marketing company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.