“The Custer fight,” a painting by Charles M. Russell in 1903. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, showing Native Americans on horseback in foreground. One of their leaders was Lakota warrior Crazy Horse. Library of Congress image.

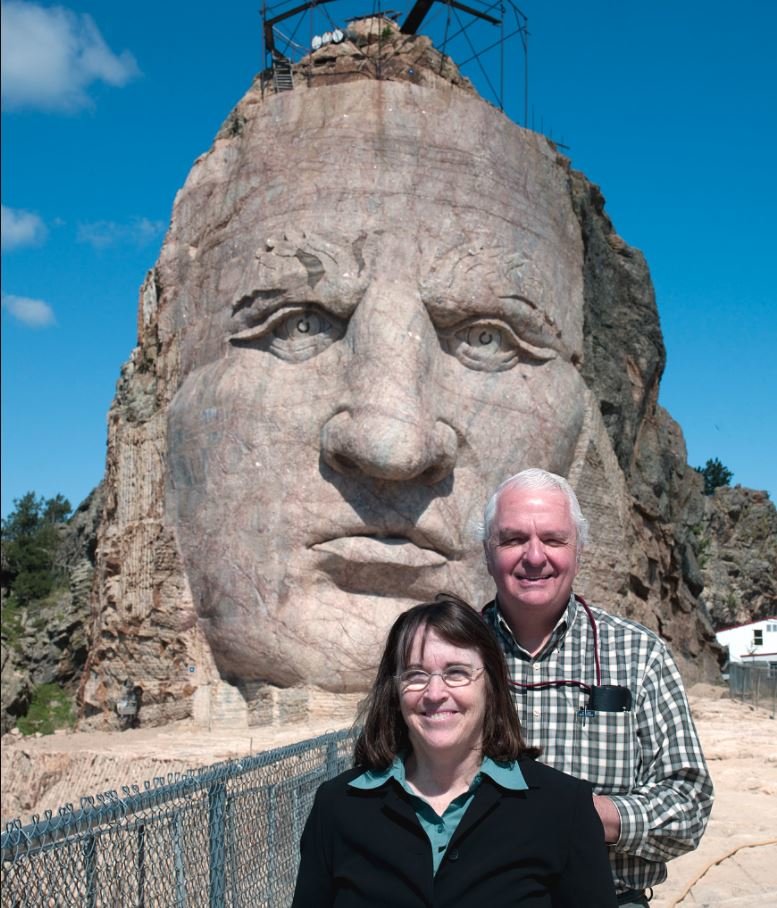

More than a century after he died, the Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, who famously fought General Custer in the Battle of Little Bighorn, is thought of as transcendent force – attuned to the universe in a special way – though he’s often commemorated in ways that are somewhat odd. He’s the subject, for example, of a gargantuan (and controversial) mountain-top sculpture in South Dakota which – if ever finished – will be bigger than Mount Rushmore. And his name is the inspiration for a strip joint in Montmartre that has billed itself as “the most sophisticated cabaret in Paris.”

It’s easy to forget that Crazy Horse was once actually a real person, even if the historical record is often frustratingly incomplete. But Castle McLaughlin’s latest publication brings readers into the world of the real Crazy Horse. Her book, titled A Lakota War Book from the Little Bighorn, also delves into one of the more intriguing art historical “Who-Done-Its” in recent memory.

Drawings by Natives, for Natives

In 1930 the estate of Boston philanthropist George White donated a ledgerbook filled with drawings by Native American artists to Harvard’s Houghton Library. For 70 years it sat on the shelves, unnoticed, until the late Tom Ford, a member of the library’s staff, brought it to the attention of McLaughlin, the curator of North American ethnography at Harvard’s Peabody Museum.

Ledgerbooks by Native Americans are relatively common, but most of them date from after the Indian Wars, when Native prisoners in Florida composed and sold them to tourists for much-needed cash. This book stands out because of its early (and quite specific) production date. As McLaughlin documents in detail, a US soldier discovered the book near the scaffold burial of an Indian Chief on the Little Bighorn battlefield, shortly after Custer’s defeat. It was made not for tourists, but rather is an actual Native American “War Book,” made by Native Americans, for Native Americans, and filled with drawings of war exploits.

The 77 drawings in the book record warfare and horse stealing on the plains; 11 show the protagonist killing, wounding, or striking a US Soldier or civilian, often with uniforms or guns that are rendered so precisely that we can date the drawing to its conception. Most of the drawings are clearly autobiographical, showing diary-like depictions of day-to-day warrior life.

For Native American warriors, such drawings recorded history. They acted as a means to boast about their battlefield accomplishments and to improve their status among fellow warriors. They also believed the images resulted in “good magic” for future conflicts.

This specific book contains drawings that portray episodes from Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868), during which Cheyenne and Lakota warriors – including Crazy Horse – defended the Yellowstone and Powder River Valleys. It was the only war ever “won” by western Native Americans, who forced the US military to retreat from the Bozeman trail.

At first glance, the drawings may look childish. But as Picasso has pointed out, a drawing’s intelligence isn’t simply a matter of academic technique. Under McLaughlin’s masterful guidance, we come to recognize that, in fact, the drawings in this book exhibit extraordinary intelligence of observation. Every detail is telling, whether it’s a dragonfly painted on a shield or the way war paint was applied to the horses.

As McLaughlin explains, these drawings are as rich and informative as any Euro-American literary text, although they speak in the language of images rather than letters, and shape reality within parameters set by a very different cultural framework. It’s a remarkable lesson in the importance of examining something very closely, of learning to look at images in new ways.

Who is artist D?

Since no names accompany the drawings, McClaughlin designated each artist with a letter – A through F – and, through careful analysis, set out to discover who the artists might have been. Artist E, for example, drew himself connected to a bird in the sky with a wiggly line. He may well have been the warrior Thunderhawk, who, after the murder of Crazy Horse, returned the body to Crazy Horse’s wife. Then there’s artist B, who showed himself killing a bugler. This could be High Backbone, a friend of Crazy Horse’s who appears to have killed a US Army bugler in the Fetterman fight.

But the focus of McLaughlin’s detective work is artist D, who, in one drawing, drew himself streaked with yellow body paint, and depicted his horse with lightning bolts lining its legs. It’s just how Amos Bad Heart Bull – a nephew of Red Cloud – portrays Crazy Horse and his mare in a separate drawing of Crazy Horse in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Could artist D be Crazy Horse? The episode shows the death of a US army officer and sergeant, which precisely corresponds with a December 1866 skirmish in which Crazy Horse killed Lieutenant Horatio S. Bingham and Sergeant Gideon R. Bowers.

There’s also something about the drawings that fits with what we know of Crazy Horse: they seem to possess a peculiar and distinct energy. Even among his peers, Crazy Horse was known for possessing a mystical aura – a presence that set him apart from the others. As his cousin and contemporary Black Elk once explained:

Crazy Horse dreamed and went into the world where there is nothing but the spirits of things. That is the real world that is behind this one, and everything we see here is something like a shadow from that world…. It was this vision that gave him his great power, for when he went into a fight, he had only to think of that world to be in it again, so that he could go through anything and not be hurt.

Likewise the work of artist D differs from the other drawings. As McLaughlin notes: “His drawings testify that he is a deeply spiritual man whose success in war follows from his relationships with higher powers, especially the thunder beings…Artist D’s dynamic, colorful, well-executed drawings…seem to express a contained inwardly focused energy that sets them apart from the rest of the images in the book.”

While the evidence is circumstantial, McLaughlin’s patient accumulation of evidence is powerfully persuasive. By the time you reach the end of her account, it’s hard to avoid the eerie feeling that you’re in the presence of drawings by Crazy Horse himself.

This story appeared first in The Conversation on Jan. 14, 2015. The Conversation is a community of more than 135,400 academics and researchers from 4,192 institutions.

Read Next: Custer Made His Last Stand at Little Bighorn 145 Years Ago Today

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.