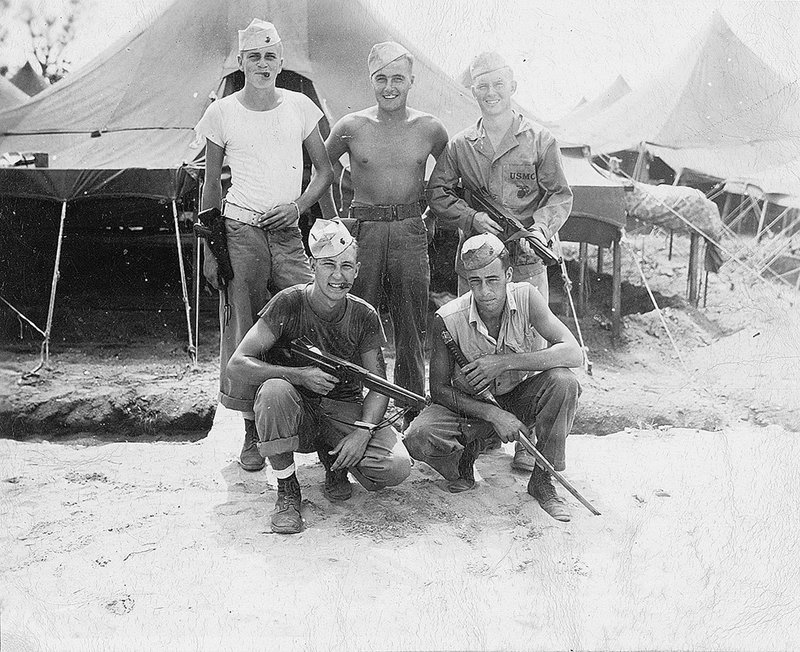

Marine Corps’ 27th Regiment, 2nd Battalion landing on Iwo Jima in 1945. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

The nose of their amphibious tank entered the ocean and bobbed through the waves en route toward the reef of Saipan, the largest archipelago among the Northern Mariana Islands. Wayne “Twig” Terwilliger, a radioman assigned to the 2nd Armored Amphibian Battalion of the 2nd Marine Division, watched helplessly as they crept over the reef toward the beach into the range of Japanese defensive positions.

“I started seeing these puffs of water all around us, and it took a second to realize what was causing them,” Terwilliger wrote in his autobiography. “Then we heard small arms fire hitting our tank, and the reality sank in: there were people on that island who wanted us dead.”

Prior to the invasion of Saipan, U.S. Navy frogmen conducted a daring reconnaissance mission in advance of the assault force. Valuable intelligence collected had provided the amphibious tanks with adjustments to successfully land on the beach — but they didn’t anticipate how their tracked vehicles would navigate earth displaced by battlefield weaponry in combat.

While the amphibious tanks attempted to land on the beach, some were destroyed and others became trapped in craters left from mortar shells in the sand. “Japanese mortars kept whistling over our heads,” Terwilliger said, describing his first hours in combat stuck inside a large, green, immobilized target. “Most of them were headed toward the beach area, but we never knew when one would come our way. We also had no idea how long we’d be stuck there. We were there at least a couple of hours, though it seemed like forever.”

Terwilliger’s crew left the disabled tank and scattered, diving into foxholes situated out of the open. Gunfire snapped overhead, and explosions from mortars and grenades flung a wall of shrapnel through the air. Before they could catch their breath the rumbling sound of an unfamiliar tank grew nearer. Their horror realized Japanese armor with the big red “Rising Sun” emblem on the tank’s side was blasting its 37mm turret gun and had stopped directly beside their foxhole.

With nothing more than a few hand grenades, his crew couldn’t defend themselves. They pulled the pins and hurled them at the tank before fleeing for cover, but there wasn’t any within crawling distance. Terwilliger ran under heavy fire across open ground until he reached an old Japanese artillery piece. His stomach dropped when he realized he had run the wrong way. He found a little path, as if all of the enemy’s attention was upon him, and sprinted toward the beach as bullets zipped passed. He looked over his shoulder to find the Japanese tank trailing his every move.

He zigzagged through the soft sand to give the tank a harder target to hit. Marines waved and yelled to get his attention, and he dashed over a small sand dune for cover. “I looked back just in time to see one of our tanks made a direct hit, which knocked the Japanese tank on its side,” Terwilliger reflected. “That was my first six or seven hours of combat.”

Terwilliger served honorably in the U.S. Marine Corps, participating in the invasion of Tinian, as well as being among the first amphibious tanks to lead the invasion of Iwo Jima. During World War II, many amateur and professional baseball players joined service teams when not actively participating in combat operations.

“We didn’t have any spikes so we played in the boots the Marines issued us,” Terwilliger told ESPN. “You would have an air-raid sound during the game, you would scatter and then come back later to finish.” Terwilliger helped lead his battalion team to a 28-0 record, even winning the 2nd Division Championship — not bad for a high school second baseman.

When news of Japan’s surrender in 1945 came in, Terwilliger was in Hawaii, preparing to invade mainland Japan. He left the military that same year and went on to have a successful career as a player, coach, and manager in Major League Baseball. For 60 years, taking Terwilliger well into his 80s, he remained active in America’s national pastime. He was a teammate of Jackie Robinson — the first Black player to break the color barrier — and a personal friend of Ted Williams, one of the greatest hitters in all of baseball. However, Terwilliger’s most prized experience was his service as a U.S. Marine.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.