Partly Smoky, With a Chance of Shrapnel — The Failed Weather Underground Movement

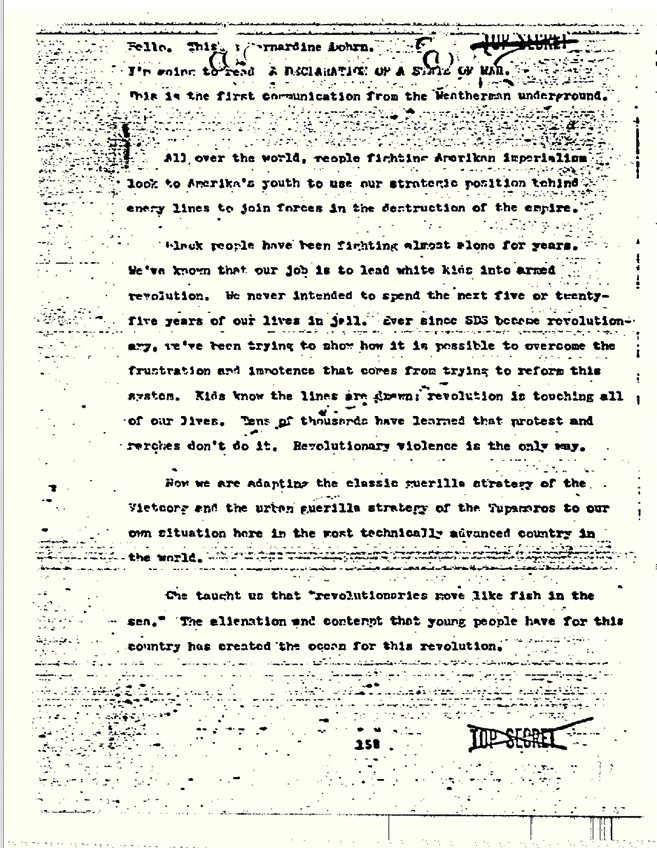

The Weatherman Underground movement started as a student communist organization against the Vietnam War and racism. It eventually adopted violent methods. Screenshot from YouTube.

In the end, some hippies resorted to using bombs to make sure everyone understood their message of peace and love.

Beginning in 1969 as a Vietnam War protest group, the Weather Underground Organization stood out for its brazen acts of domestic terrorism. Not quite the love you take equaling the love you make.

Initially known as the Students for a Democratic Society, the organization split in 1969, creating two very different factions. One was the Worker Student Alliance: a political party that promoted Maoist communism. The second was the Revolutionary Youth Movement, which ultimately devolved into a militant, far-left organization that named itself the Weather Underground Organization, or just Weathermen, as the FBI sometimes referred to the members.

They published their 1969 manifesto, You Don’t Need a Weatherman To Know Which Way the Wind Blows, as an homage to a Bob Dylan song. The document, signed by 11 people, propagated the Leninist theory for revolution. It read, “The goal is the destruction of US imperialism and the achievement of a classless world: world communism.”

Weather Underground leadership was dissatisfied with the lack of participation in and national attention for their cause — revolution against American imperialism. So in late 1969, inspired by the antics at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the Weathermen called a “war council” in Flint, Michigan, to advocate for more headline-grabbing actions.

The Weathermen invoked the need for guerrilla warfare on US soil, admiring the communist revolutions of the Soviets, Cubans, and North Vietnamese. Some members even traveled to Cuba to meet with North Vietnamese representatives and discuss their experiences as revolutionaries.

The group also championed counterculture icons. Bernardine Dohrn, one of the original signers of the manifesto and a leading voice in the Weathermen, claimed to admire Charles Manson.

“First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, then they even shoved a fork into the victim’s stomach. Wild!” Dohrn said, as reported by historian and sociologist Todd Gitlin in The Sixties. Later, Dohrn would salute using four fingers, referring to the tines of the fork that Leslie Van Houten, a Manson family member, had left in the body of Leno LaBianca only months beforehand.

Unlike the Manson family, which caught the FBI by surprise, the Weather Underground earned its “terrorist organization” label relatively soon after its inception. The organization was monitored by the FBI’s Cointelpro program, a counterintelligence operation. Even after Hoover disbanded Cointelpro in 1971, the Weathermen remained in the FBI’s crosshairs.

At one point, the FBI opted to expand its 10 most wanted to its 16 most wanted — a move solely intended to target Weather Underground leadership.

“We saw ourselves as contemporary John Browns, full of moral fervor to stop the senseless war in Vietnam,” Mark Rudd, a former member of the Weathermen, said in a 2020 New York Times opinion piece. “We also wanted to show solidarity with black revolutionaries ruthlessly targeted by the police and the federal government.”

Underscoring his regret for using violence to curb violence, Rudd added: “We didn’t realize that the violence we claimed we hated had infected our souls. […] No one is innocent, we thought.”

Betraying their peaceful objectives, the Weathermen resorted to a decidedly violent modus operandi. On Oct. 6, 1969, they bombed their first target: the Haymarket Memorial Statue of a policeman in Chicago, Illinois. The Weathermen bombed the statue a second time after the city repaired damage from the first attack.

No one was injured in the blasts.

The Weathermen had a habit of sending warning letters, nicknamed “weather reports,” to their targets, which gave people ample time to evacuate. In their letters, Weathermen militants cited their grievances, which usually involved US government actions — such as the bombing of North Vietnam’s capital of Hanoi or the May 1970 Kent State shooting.

According to a 2003 article in The Guardian, the Weathermen were “urban terrorists who never killed anyone — except themselves.” While group members were building a bomb in an apartment complex in New York City’s Greenwich Village in March 1970, the device prematurely detonated and killed three Weathermen militants. Two others were injured and managed to escape. The explosion vaporized the three would-be bomb-makers and destroyed the four-story townhouse.

Contrary to The Guardian’s reporting, the Weathermen’s militants did also kill bystanders. Notably, former members of the radical group took part in the 1981 robbery of a Brink’s armored car, during which a guard and two policemen were murdered. Among the dead was Sgt. Waverly Brown, the first Black police officer in Nyack County, New York. During the Brink’s robbery, four Weathermen militants acted as getaway drivers for six members of the Black Liberation Army.

The four Weather Underground radicals — Kathy Boudin, Judith Alice Clark, Marilyn Buck, and David Gilbert — were later convicted and sentenced to decades in prison for their roles in the deadly robbery. After spending 22 years in prison, Boudin, one of the two survivors of the 1970 Greenwich Village blast, was paroled and granted an adjunct professorship at Columbia University’s School of Social Work in 2008.

During the 1970s, the Weathermen devolved into an unruly criminal enterprise and all but abandoned their original anti-war intentions. The documentary The Weather Underground called the 1981 Brink’s robbery the “unofficial end” of the Weathermen.

Read Next:

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.