Machine gun set up in railroad shop. Co. A, 9th Machine Gun Battalion. Chateau Thierry, France, on June 7, 2018. National Archives photo.

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war against Germany and entered World War I. Since August 1914, the war between the Central and Entente Powers had devolved into a bloody stalemate, particularly on the Western Front. That was where the U.S. would enter the engagement.

How prepared was the country’s military to enter a modern conflict? The war was dominated by industrially made lethal technology, like no war had been before. That meant more death on European battlefields, making U.S. soldiers badly needed in the trenches. But America’s longstanding tradition of isolationism meant that in 1917 U.S. forces needed a lot of support from overseas allies to fight effectively.

In Europe, American combat troops would encounter new weapons systems, including sophisticated machine guns and the newly invented tank, both used widely during World War I. American forces had to learn to fight with these new technologies, even as they brought millions of men to bolster the decimated British and French armies.

In certain areas of military technology, the United States was well-prepared. The basic infantrymen of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps were equipped with the Model 1903 Springfield rifle. Developed after American experience against German-made Mausers in the Spanish American War, it was an excellent firearm, equal or superior to any rifle in the world at the time.

The Springfield offered greater range and killing power than the U.S. Army’s older 30-40 Krag. It was also produced in such numbers that it was one of the few weapons the U.S. military could deploy with to Europe.

Machine guns were another matter. In 1912, American inventor Isaac Lewis had offered to give the U.S. Army his air-cooled machine gun design for free. When he was rejected, Lewis sold the design to Britain and Belgium, where it was mass-produced throughout the war.

With far more soldiers than supplies of modern machine guns, the U.S. Army had to adopt several systems of foreign design, including the less-than-desirable French Chauchat, which tended to jam in combat and proved difficult to maintain in the trenches.

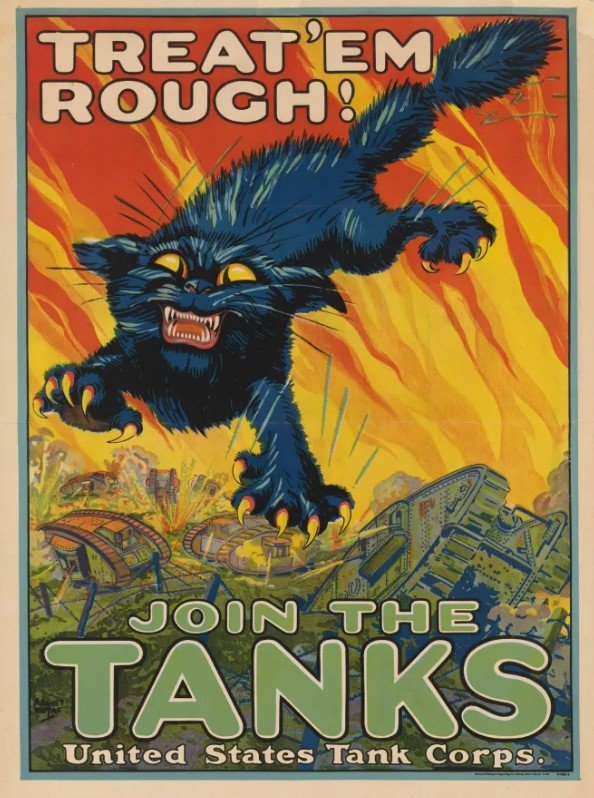

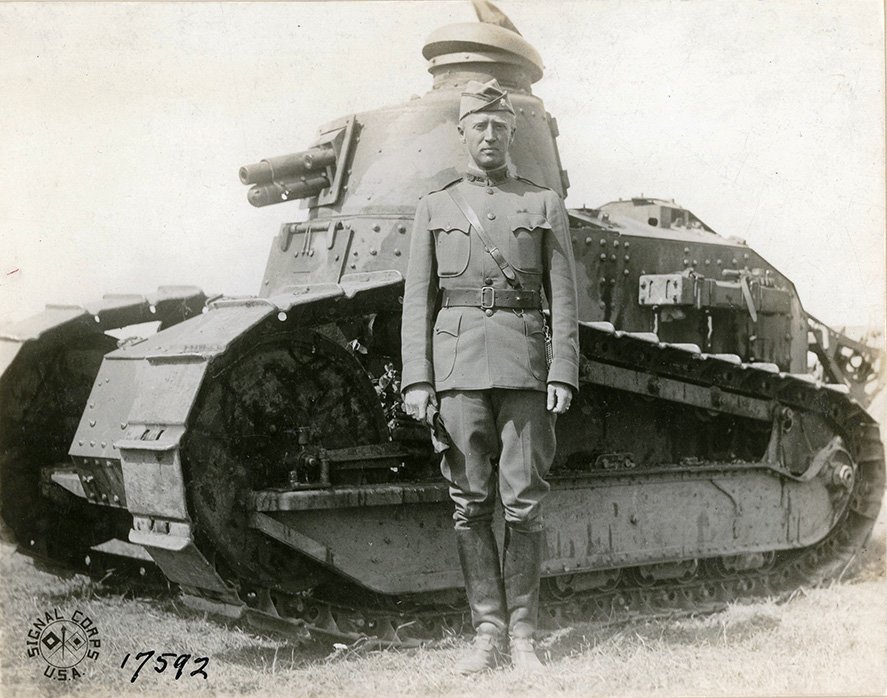

American soldiers fared better with the Great War’s truly new innovation, the tank. Developed from the need to successfully cross “No Man’s Land” and clear enemy-held trenches, the tank had been used with limited success in 1917 by the British and the French. Both nations had combat-ready machines available for American troops.

After the U.S. entered the war, American industry began tooling up to produce the French-designed Renault FT light tank. But the American-built tanks, sometimes called the “six-ton tank,” never made it to the battlefields of Europe before the Armistice in November 1918.

Instead, U.S. ground forces used 239 of the French-built versions of the tank, as well as 47 British Mark V tanks. Though American soldiers had never used tanks before entering the war, they learned quickly. One of the first American tankers in World War I was then-Captain George S. Patton, who later gained international fame as a commander of Allied tanks during World War II.

Also new to Americans was poison gas, an early form of chemical warfare. By 1917 artillery batteries on both sides of the Western Front commonly fired gas shells, either on their own or in combination with other explosives. Before soldiers were routinely equipped with gas masks, thousands died in horrific ways, adding to the already significant British and French casualty totals.

Scientists on both sides of the war effort worked to make gas weapons as effective as possible, including by devising new chemical combinations to make mustard gas, chlorine gas, phosgene gas and tear gas. The American effort was substantial: According to historians Joel Vilensky and Pandy Sinish, “Eventually, more than 10 percent of all the chemists in the United States became directly involved with chemical warfare research during World War I.”

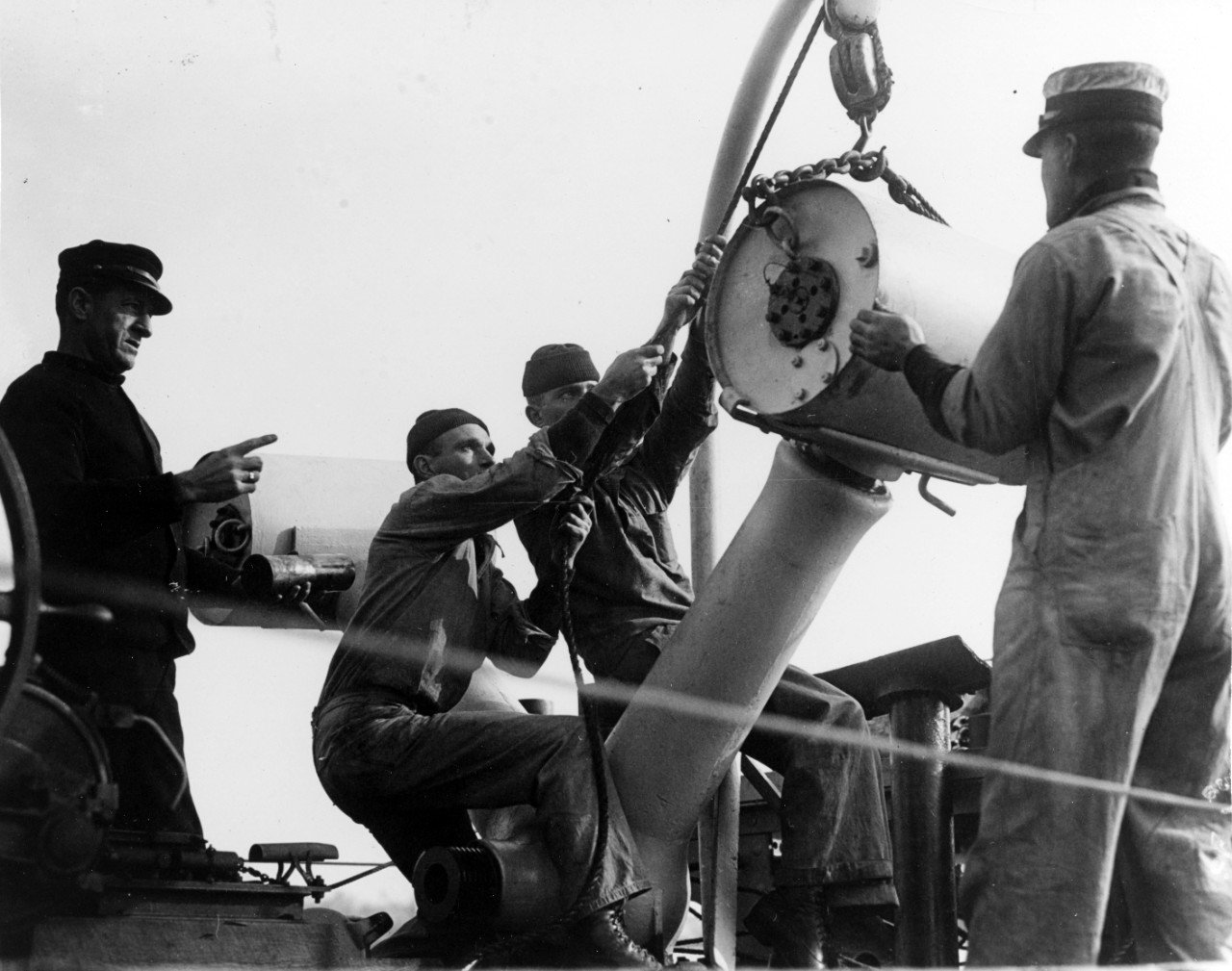

All the manpower coming from the U.S. would not have meant much without safe transportation to Europe. That meant having a strong navy. The U.S. Navy was the best-prepared and best-equipped of all the country’s armed forces. For many years, it had been focusing much of its energy on preparing for a surface naval confrontation with Germany.

But a new threat had arisen: Germany had made significant progress in developing long-range submarines and devising attack tactics that could have posed severe threats to American shipping. German Navy U-boats had, in fact, devastated British merchant fleets so badly by 1917 that British defeat was imminent.

Naval History and Heritage Command photo.

In May 1917, the British Royal Navy pioneered the convoy system, in which merchant ships carrying men and materiel across the Atlantic didn’t travel alone but in large groups. Collectively protected by America’s plentiful armed escort ships, convoys were the key to saving Britain from defeat and allowing American ground forces to arrive in Europe nearly unscathed. In fact, as military historian V.E. Tarrant wrote, “From March 1918 until the end of the war, two million U.S. troops were transported to France, for the loss of only 56 lives.”

Some of those Americans who made it to Europe climbed above the rest – right up into the air. The U.S. had pioneered military aviation. And in 1917, air power was coming into its own, showing its potential well beyond just intelligence gathering. Planes were becoming offensive weapons that could actively engage ground targets with sufficient force to make a difference on the battlefield below.

But with fewer than 250 planes, the U.S. was poorly prepared for an air war in Europe. As a result, American pilots had to learn to fly British and French planes those countries could not man.

Despite often lacking the weapons and technology required for success, it was ultimately the vast number of Americans – afloat, on the ground and in the air – and their ability to adapt and use foreign weapons on foreign soil that helped turn the tide of the war in favor of the Allies.

This story appeared first in The Conversation on Oct. 16, 2019. The Conversation is a community of more than 135,400 academics and researchers from 4,192 institutions.

Read Next: When Players Collaborated with Gamblers to Throw the World Series

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.