“The arrival of the American Fleet at Scapa Flow, 7 December 1917” Oil on canvas by Bernard F. Gribble, depicting the U.S. Navy’s Battleship Division Nine being greeted by British Admiral David Beatty and the crew of the British warship Queen Elizabeth. Ships of the American column are (from front) USS New York (BB-34), USS Wyoming (BB-32), USS Florida (BB-30) and USS Delaware (BB-28). Courtesy of the U.S. Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command image.

On July 7, 1919, a group of U.S. military members dedicated Zero Milestone – the point from which all road distances in the country would be measured – just south of the White House lawn in Washington, D.C. The next morning, they helped to define the future of the nation.

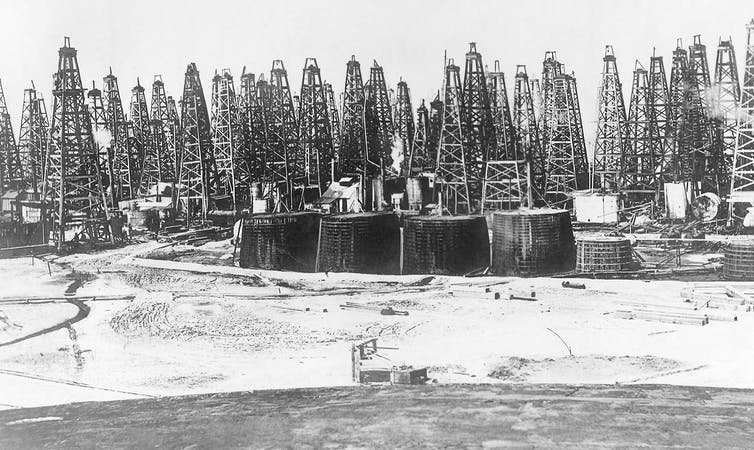

Instead of an exploratory rocket or deep-sea submarine, these explorers set out in 42 trucks, five passenger cars and an assortment of motorcycles, ambulances, tank trucks, mobile field kitchens, mobile repair shops and Signal Corps searchlight trucks. During the first three days of driving, they managed just over five miles per hour. This was most troubling because their goal was to explore the condition of American roads by driving across the U.S.

Participating in this exploratory party was U.S. Army Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower. Although he played a critical role in many portions of 20th-century U.S. history, his passion for roads may have carried the most significant impact on the domestic front. This trek, literally and figuratively, caught the nation and the young soldier at a crossroads.

Returning from World War I, Ike was entertaining the idea of leaving the military and accepting a civilian job. His decision to remain proved pivotal for the nation. By the end of the first half of the century, the roadscape – transformed with an interstate highway system while he was president – helped remake the nation and the lives of its occupants.

For Ike, though, roadways represented not only domestic development but also national security. By the early 1900s it become clear to many administrators that petroleum was a strategic resource to the nation’s present and future.

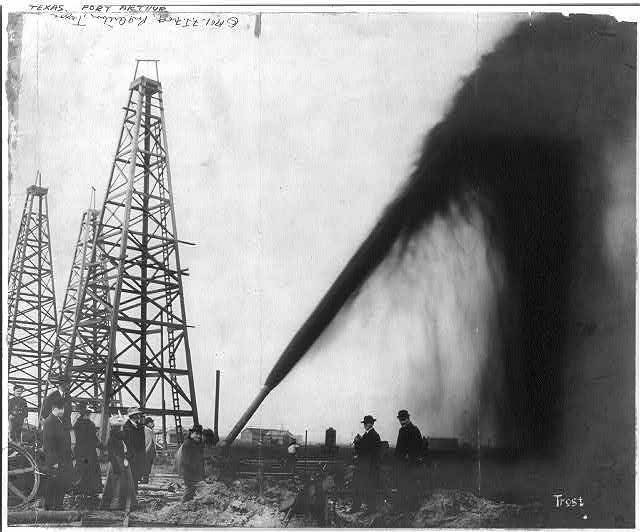

At the start of World War I, the world had an oil glut since there were few practical uses for it beyond kerosene for lighting. When the war was over, the developed world had little doubt that a nation’s future standing in the world was predicated on access to oil. “The Great War” introduced a 19th-century world to modern ideas and technologies, many of which required inexpensive crude.

During and after World War I, there was a dramatic change in energy production, shifting heavily away from wood and hydropower and toward fossil fuels – coal and, ultimately, petroleum. And in comparison to coal, when utilized in vehicles and ships, petroleum brought flexibility as it could be transported with ease and used in different types of vehicles. That in itself represented a new type of weapon and a basic strategic advantage. Within a few decades of this energy transition, petroleum’s acquisition took on the spirit of an international arms race.

Even more significant, the international corporations that harvested oil throughout the world acquired a level of significance unknown to other industries, earning the encompassing name “Big Oil.” By the 1920s, Big Oil’s product – useless just decades prior – had become the lifeblood of national security to the U.S. and Great Britain. And from the start of this transition, the massive reserves held in the U.S. marked a strategic advantage with the potential to last generations.

As impressive as the U.S.’ domestic oil production was from 1900-1920, however, the real revolution occurred on the international scene, as British, Dutch and French European powers used corporations such as Shell, British Petroleum and others to begin developing oil wherever it occurred.

During this era of colonialism, each nation applied its age-old method of economic development by securing petroleum in less developed portions of the world, including Mexico, the Black Sea area and, ultimately, the Middle East. Redrawing global geography based on resource supply (such as gold, rubber and even human labor or slavery) of course, was not new; doing so specifically for sources of energy was a striking change.

“World War I was a war,” writes historian Daniel Yergin, “that was fought between men and machines. And these machines were powered by oil.”

When the war broke out, military strategy was organized around horses and other animals. With one horse on the field for every three men, such primitive modes dominated the fighting in this “transitional conflict.”

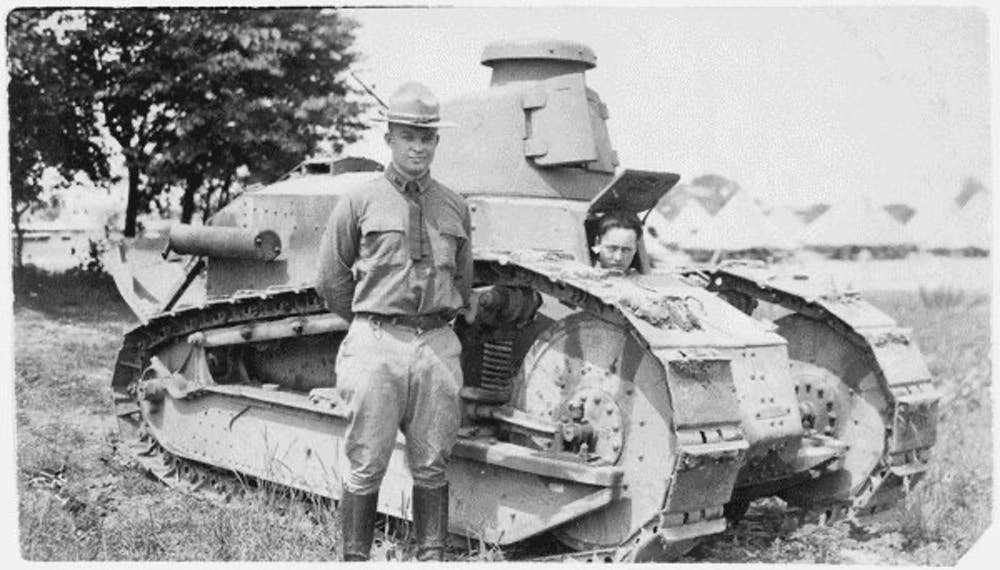

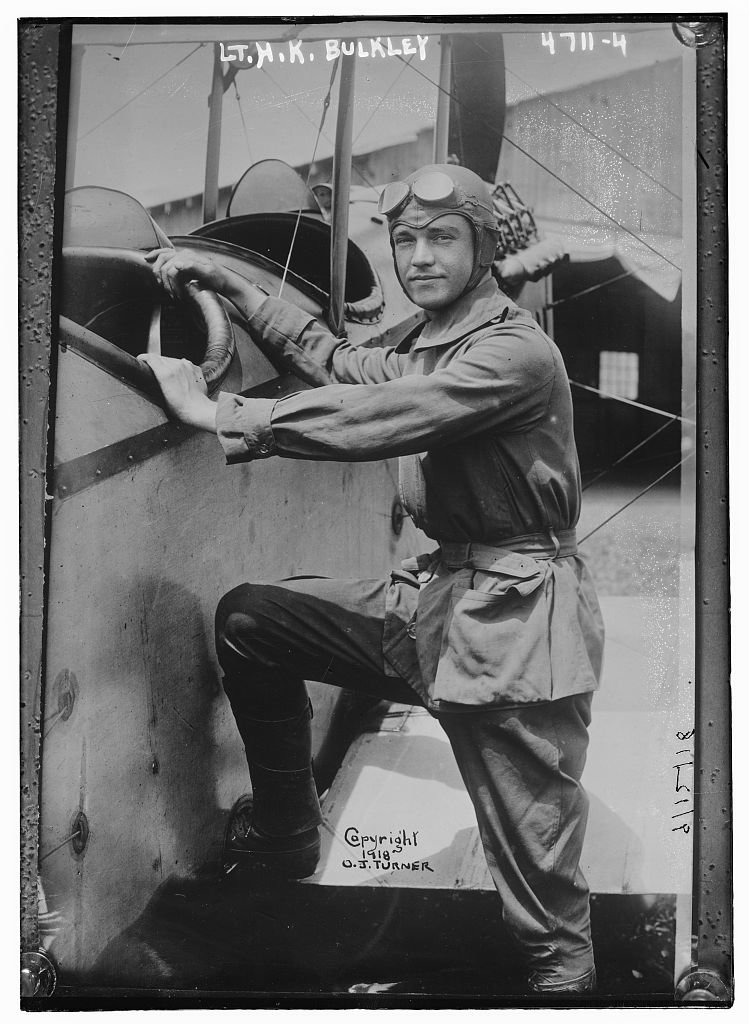

Throughout the war, the energy transition took place from horsepower to gas-powered trucks and tanks and, of course, to oil-burning ships and airplanes. Innovations put these new technologies into immediate action on the horrific battlefield of World War I.

It was the British, for instance, who set out to overcome the stalemate of trench warfare by devising an armored vehicle that was powered by the internal combustion engine. Under its code name “tank,” the vehicle was first used in 1916 at the Battle of the Somme. In addition, the British Expeditionary Force that went to France in 1914 was supported by a fleet of 827 motor cars and 15 motorcycles; by war’s end, the British army included 56,000 trucks, 23,000 motorcars and 34,000 motorcycles. These gas-powered vehicles offered superior flexibility on the battlefield.

In the air and sea, the strategic change was more obvious. By 1915, Britain had built 250 planes. In this era of the Red Baron and others, primitive airplanes often required that the pilot pack his own sidearm and use it for firing at his opponent. More often, though, the flying devices could be used for delivering explosives in episodes of tactical bombing. German pilots applied this new strategy to severe bombing of England with zeppelins and later with aircraft. Over the course of the war, the use of aircraft expanded remarkably: Britain, 55,000 planes; France, 68,0000 planes; Italy, 20,000; U.S., 15,000; and Germany, 48,000.

With these new uses, wartime petroleum supplies became a critical strategic military issue. Royal Dutch/Shell provided the war effort with much of its supply of crude. In addition, Britain expanded even more deeply in the Middle East. In particular, Britain had quickly come to depend on the Abadan refinery site in Persia, and when Turkey came into the war in 1915 as a partner with Germany, British soldiers defended it from Turkish invasion.

When the Allies expanded to include the U.S. in 1917, petroleum was a weapon on everyone’s mind. The Inter-Allied Petroleum Conference was created to pool, coordinate and control all oil supplies and tanker travel. The U.S. entry into the war made this organization necessary because it had been supplying such a large portion of the Allied effort thus far. Indeed, as the producer of nearly 70 percent of the world’s oil supply, the U.S.’ greatest weapon in the fighting of World War I may have been crude. President Woodrow Wilson appointed the nation’s first energy czar, whose responsibility was to work in close quarters with leaders of the American companies.

When the young Eisenhower set out on his trek after the war, he deemed the party’s progress over the first two days “not too good” and as slow “as even the slowest troop train.” The roads they traveled across the U.S., Ike described as “average to nonexistent.”

He continued: “In some places, the heavy trucks broke through the surface of the road and we had to tow them out one by one, with the caterpillar tractor. Some days when we had counted on sixty or seventy or a hundred miles, we could do three or four.”

Eisenhower’s party completed its frontier trek and arrived in San Francisco, California on Sept. 6, 1919. Of course, the clearest implication that grew from Eisenhower’s trek was the need for roads. Unstated, however, was the symbolic suggestion that matters of transportation and of petroleum now demanded the involvement of the U.S. military, as it did in many industrialized nations.

The emphasis on roads and, later, particularly on Ike’s interstate system was transformative for the U.S.; however, Eisenhower was overlooking the fundamental shift in which he participated. The imperative was clear: Whether through road-building initiatives or through international diplomacy, the use of petroleum by his nation and others was now a reliance that carried with it implications for national stability and security.

Seen through this lens of history, petroleum’s road to essentialness in human life begins neither in its ability to propel the Model T nor to give form to the burping plastic Tupperware bowl. The imperative to maintain petroleum supplies begins with its necessity for each nation’s defense. Although petroleum use eventually made consumers’ lives simpler in numerous ways, its use by the military fell into a different category entirely. If the supply was insufficient, the nation’s most basic protections would be compromised.

After World War I in 1919, Eisenhower and his team thought they were determining only the need for roadways – “The old convoy,” he explained, “had started me thinking about good, two lane highways.”

At the same time, though, they were declaring a political commitment by the U.S. And thanks to its immense domestic reserves, the U.S. was late coming to this realization. Yet after the “war to end all wars,” it was a commitment already being acted upon by other nations, notably Germany and Britain, each of whom lacked essential supplies of crude.

This story appeared first in The Conversation on April 3, 2017. The Conversation is a community of more than 135,400 academics and researchers from 4,192 institutions.

Read Next: Wall of White: Go Inside the US Coast Guard’s Afognak Island Rescue

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.