‘Climb to Glory’ — A History of the US Army’s 10th Mountain Division

Pfc. John Eichenberger, 30, of Portland, Oregon, helps Staff Sgt. Cody Collins, 25, left, of Joy, Kentucky, of the US Army's 2nd Platoon Apache Company of 2nd Battalion 87th Infantry Regiment, part of the 3rd Combat Brigade 10th Mountain Division based out of Fort Drum, New York, out of a ditch while patrolling for roadside bombs in the Tangi Valley in Afghanistan's Wardak Province, Sunday Aug. 16, 2009. AP photo by David Goldman.

The 10th Mountain Division is among the most storied divisions in the United States Army. The unit was first mustered into service during World War II to fight in Italy's northern Apennine Mountains. It played a minor but important role during the Black Hawk Down saga in Mogadishu. Later, it became the most deployed division during the Global War on Terror, battling insurgents in the mountains of Afghanistan and the city streets of Iraq.

While generations of 10th Mountain soldiers built the division’s reputation as a formidable fighting force, their contributions to society extend beyond the battlefield. Among other things, they were instrumental in the formation of the modern ski industry, they helped improve mountain rescue tactics, and even inspired a few hit country music songs. Here is everything else you should know about the 10th Mountain Division and its “climb to glory.”

National Ski Patrol to Elite Alpine Troops

Members of what was then called the 10th Light Division (Alpine) prepare for ski training at Camp Hale, Colorado. The National Ski Patrol, which Charles Minot Dole directed, recruited men for the division. US Army photo.

In 1938, Charles “Minnie” Dole and 94 volunteers founded the National Ski Patrol in response to a friend’s ski accident in Massachusetts. A year later, when the Soviet Union invaded Finland, Finnish troops took to their skis to wage guerrilla war. Hearing of their exploits in the hazardous Nordic mountains, Dole proposed that the US Army create its own highly specialized winter warfare unit. The Army liked the idea, and in November 1941, the 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment, was activated for service at Fort Lewis, Washington.

The unit’s first members were all volunteers who, like Dole, had experience living and working in the mountains. They included skiers, mountaineers, trappers, and loggers.

In 1943, the 87th Mountain relocated to Camp Hale, Colorado. There, the unit expanded into the 10th Light Division (Alpine). Its members trained in the Rocky Mountains, learning how to conduct combat maneuvers on snowshoes through 12-foot snow while wearing 100-pound rucksacks. The drilling was so arduous that soldiers nicknamed Camp Hale “Camp Hell.”

Before the unit shipped overseas, it was rechristened the 10th Mountain Division. It arrived in Italy in January 1945, with orders to clear and secure Mount Belvedere in the snowy Apennine Mountains.

A machine gunner and two riflemen of Company "K" of the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division, cover an assault squad routing Germans out of a building in the background. Sassomolare Area, Italy. Porretta Moderna Highway, March 4, 1945. Wikimedia Commons photo.

On the night of Feb. 18, approximately 1,000 ski soldiers completed a 2,000-foot ascent up Mount Belvedere to assault a German stronghold along Riva Ridge. The fighting raged for a week straight. By the time the 10th Mountain finally succeeded in taking the ridgeline, 213 of its troops had been killed and nearly 800 more were wounded.

From Mount Belvedere, the 10th Mountain continued fighting and taking more ridgelines from the Nazis and eventually seized control of the Po Valley in northern Italy. Approximately 1,000 of the unit’s soldiers were killed in just six months of fighting. One soldier, Pfc. John Magrath, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for single-handedly charging and capturing multiple enemy machine gun nests in the area of Castel d’Aiano. The same day, and in the same battle, future US Sen. Bob Dole, a member of Magrath’s regiment, was grievously wounded by a German shell while attempting to clear another machine-gun nest with a grenade.

The 10th Mountain remained in the European theater until the Germans formally surrendered on May 2, 1945. They then returned to the US to commence preparations for the planned invasion of Japan. However, their deployment to the Pacific was canceled following the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On Nov. 30, 1945, the 10th Mountain Division was deactivated at Camp Carson, Colorado.

Related: How Charles “Minnie” Dole Created The National Ski Patrol

10th Mountain Division Vets Created the Ski Industry

The National Ski Patrol screened potential candidates before they could join the 10th Mountain Division. The ski troops fought in Italy during World War II and returned home to transform the skiing industry. Photo courtesy of the National Ski Patrol.

After the war, many 10th Mountain veterans leveraged their unique skill sets and experiences in the Apennines to build successful careers in America’s budding ski industry. As a result of their work, the production of specialized ski equipment and clothing became a more commercialized effort. In time, as more and more Americans took up snow sports, the United States became a worldwide leader in the ski industry.

Related: The Crag Rats: How a Band of Outdoor Hobbyists Transformed Mountain Rescue in the Pacific Northwest

The 10th Mountain Division Transformed Mountain Rescue

Early Crag Rats with their gear. Photo courtesy of Crag Rats historian Bill Pattison.

While some veterans of the 10th Mountain Division pursued careers in the ski industry, others found post-military employment with mountain search-and-rescue teams. Some were recruited by the Crag Rats, the nation’s first mountain search-and-rescue team. Based in Oregon, the organization already had two decades of experience saving lives on the slopes of Mount Hood when World War II ended, yet they still had plenty to learn from the former ski soldiers. And since snow sports were becoming more popular in America — also partly thanks to 10th Mountain veterans — the Crag Rats’ services were more in-demand than ever.

“The establishment of the 10th Mountain Division resulted in organized search-and-rescue techniques, equipment, training, and ways of doing things that spurred an increase of recreational use in areas like national parks and national forests,” Bill Pattison, a Crag Rats historian who first joined the team in the 1940s, told Coffee or Die in October 2021. “The Crag Rats just went along with what was going on at the time, and our training came out of the 10th, from rope work to training manuals.”

Related: Why 10th Mountain Division’s Forgotten Platoon of Mogadishu is Fighting For Recognition

Brief Reactivation for the Cold War

Soldiers from Bravo Company, 41st Brigade Engineer Battalion, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division (LI) listen to an instructor from the Army National Guard's 86th Infantry Brigade Combat Team talk about avalanche awareness and survival techniques at Camp Ethan Allen Training Site in Jericho, Vermont, Feb. 19, 2021. US Army photo by Sgt. Elizabeth Rundell.

In 1948, just three years after the 10th Mountain was deactivated at Camp Carson, the 10th Infantry Division was stood up as its replacement. The division originally hailed from Fort Riley, Texas, and during the Korean War was strictly a training unit for new Army recruits. Later, it would be reorganized as a combat division and deployed to Germany to help deter the Soviet Union following the Warsaw Pact. The division was a component of NATO’s defense forces in Germany from 1954 to 1958, when it was relieved by the 3rd Infantry Division. The 10th Infantry was deactivated soon after.

Decades later, on Feb. 13, 1985, the 10th Mountain Division was finally reactivated. Before long, the unit, now based at Fort Drum, New York, was back in action, participating in contingency operations in Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, and other hotspots around the world.

Related: What Really Happened Before & After the Battle of Mogadishu

The Forgotten Heroes of Black Hawk Down

Members of the 10th Mountain Division’s TF 2-14 in Mogadishu in 1993. In less than a month, the unit found itself in three firefights, including an ambush at a hospital, the rescue of Courage 53, and the Battle of Mogadishu chronicled in Black Hawk Down. Photo courtesy of Olin Rossman.

In September 1993, only one week before the Black Hawk crash that ignited the infamous battle between Army special operations forces and heavily armed militants in Mogadishu, another Black Hawk helicopter — callsign Courage 53 — was shot down in the Somali capital.

Shortly after midnight on Sept. 25, Courage 53 was struck by a rocket-propelled grenade while flying a routine patrol as part of the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Somalia. Somali militiamen had targeted helicopters before, but this was the first time they succeeded in downing one. The pilots were able to crash land, but three aircrew were killed.

As Somali militants raced to the helicopter, so did a quick reaction force of American, Pakistani, and Malaysian troops. The two factions converged at the crash site and a firefight ensued. Spc. Brett Archibald, a soldier from the 10th Mountain Division’s Task Force 2-14, was manning an M-60 mounted in the turret of his Humvee. He opened up on the militants, who responded with a barrage of gunfire and rocket-propelled grenades. Archibald kept firing until he was shot in the leg and dragged to cover by his teammates.

Current soldiers and veterans of the 10th Mountain Division hold an annual run, dubbed the Mogadishu Mile, in memory of the division’s role in the Battle of Mogadishu. US Army photo by Capt. Matthew Parget.

Many years later, Archibald recalled in an interview with Coffee or Die that despite being wounded, he was eager to return to the fight. Believing the pilots were still trapped in the helicopter, he would have rather died in battle than leave them to fend for themselves. However, unbeknownst to him at the time, both pilots, though wounded, had already managed to get off the objective and would ultimately survive.

“We don’t leave a man behind, and at the point [when] I was shot, I thought we still had somebody to get,” Archibald told Coffee or Die in November 2021. “I’ve had to live with that my whole life, even though that didn’t happen.”

The QRF team eventually managed to retrieve the bodies of the three airmen who had died in the crash. Four Americans, including Archibald, were seriously wounded in the process. But the harrowing events of that day would be largely overshadowed by the even bloodier battle that erupted in Mogadishu after a second Black Hawk crashed there a week later.

Related: Courage 53: The 10th Mountain Division’s Forgotten Rescue Mission in Mogadishu

Forward Observer Remembers Fallen Medal of Honor Teammate

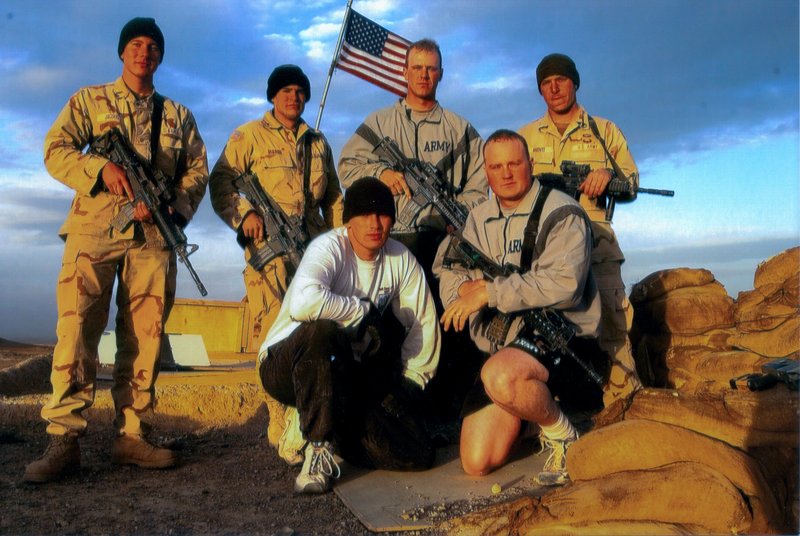

Sgt. First Class Jared Monti, standing top right, alongside other members of 10th Mountain Division in Afghanistan. US Army photo.

Between 2001 and 2014, the 10th Mountain Division deployed more than 20 times to Iraq and Afghanistan, earning the distinction of being the most-deployed conventional unit of the War on Terror. In that time, three 10th Mountain soldiers earned the Medal of Honor: Sgt. First Class Jared Monti, Lt. Col. William Swenson, and Staff Sgt. Travis Atkins.

Danny O’Neel, a former US Army forward observer who deployed twice to Iraq, served with Monti in the early 2000s. The pair were both assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division at Camp Casey in South Korea. Monti, a native of Raynham, Massachusetts, was O’Neel’s first squad leader. O’Neel can still hear him introducing himself in his raspy New England accent.

“He’s not a big-in-stature guy — he was, like, 5-foot-7 or 5-foot-8 — but he’s huge in personality,” O’Neel told Coffee or Die. “When you’re from California, you don’t hear anybody that talks like that — it sounded like he’d been smoking for, like, 40 years.”

Beyond the jokes and jabs, O’Neel credits Monti for preparing him for combat. They were members of the COLT team, which stands for Combat Observation Lasing Team. Their specialty was working at the brigade level to orchestrate fire support for frontline units.

“Jared made sure that we were excellent with accurate coordinates, so we didn’t kill any friendlies,” O’Neel recalled. “He made sure we were on our game at all times, smooth operators on the radio, and calling for the exact munitions we asked for on the exact coordinates we asked for.”

After their tour in Korea, O’Neel went to Iraq and Monti eventually deployed with the 10th Mountain Division to Afghanistan.

On June 21, 2006, Monti led a 16-man patrol on an intelligence-gathering mission in Nuristan Province. They set up a temporary observation post on the ridgeline to provide overwatch for Army units conducting an operation in the valley below.

Spc. Paul Pickett, 22, of Minden, Louisiana, right, of the US Army's Apache Company, 2nd Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment, part of the 3rd Combat Brigade 10th Mountain Division based out of Fort Drum, New York, covers an injured US soldier as a helicopter lands to evacuate the wounded after their armored vehicle hit an improvised explosive device in the Tangi Valley of Afghanistan's Wardak Province on Aug. 19, 2009. AP photo by David Goldman.

That evening, as many as 50 enemy fighters ambushed the observation post. Under threat of being overrun, Monti ordered his team to fall back into a defensive position. Then, just as he had instructed O’Neel to do, Monti calmly called for indirect fire. At one point during the battle, enemy fire struck and killed one of Monti’s men — Sgt. Patrick Lybert — and severely wounded another, Pfc. Brian Bradbury. As Bradbury lay exposed between the Americans and the insurgents, Staff Sgt. Chris Cunningham, the patrol’s sniper team leader, called out that he would attempt a rescue. “That’s my guy,” Monti replied. “I am going to get him.”

On his third and final attempt to reach Bradbury, Monti was mortally wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade. He reported his medical status over the radio just as the artillery he requested arrived, killing an estimated 22 enemy fighters. He succumbed to his wounds before the MEDEVAC helicopter arrived. Then, during the extraction, the hoist cable snapped, and Bradbury and flight medic Staff Sgt. Heath Craig fell to their deaths.

In 2011, NPR interviewed Monti’s father, Paul, about Operation Flags For Vets, a nonprofit he started following his son’s death to honor all service members killed in the line of duty. During the interview, Paul mentioned that he still drove the same black truck that had once belonged to his son. Among those listening in was Nashville songwriter Connie Harrington, who was so moved by Paul’s story that it inspired her to write“I Drive Your Truck.” Performed and recorded by Lee Brice, it was named Song of the Year by the Country Music Association in 2013.

Read Next: The Warrior Generation That Was Inspired by 9/11

Editor's Note 3/20/2023: An earlier version of this article misstated that four Silver Stars and more than 10 Bronze Stars with valor were awarded for the events that occurred in Mogadishu on Sept. 25, 1993. In fact, those awards were earned over Task Force 2-14's entire Somalia rotation, not just in that one engagement. This article has been revised accordingly.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.