The US Army Honor Guard, the 3rd US Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) Caisson Platoon, and the US Army Band, “Pershing’s Own,” conduct the funeral of US Army Staff Sgt. Bryan Black in Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia, Oct. 30, 2017. Black, a native of Puyallup, Washington, was assigned to Company A, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) on Fort Bragg, North Carolina, when he died from wounds sustained during enemy contact in the country of Niger in West Africa, Oct. 4, 2017. Even in the absence of an active war, service members continue to die from another byproduct of the GWOT — cancer. US Army photo by Elizabeth Fraser/Arlington National Cemetery.

At the far end of Arlington Cemetery, in Section 60 — the gravesites closest to Marshall Drive — are fresh burial plots. There’s a standing list of service members waiting to be buried in what has been America’s most sacred ground since the Civil War.

But America’s wars, for the moment, are over — if we are no longer fighting on foreign soil after two decades of the Global War on Terror, why are we still burying so many service members?

These combat-related deaths are not being inflicted by an enemy attacking service members; they’re the result of something born in them during their time of service that grew and consumed them from the inside. These service members died from cancer.

In this Oct. 1, 2018, file photo, President Donald Trump awards the Medal of Honor to former Army Staff Sgt. Ronald J. Shurer II for actions in Afghanistan, in the East Room of the White House in Washington. Miranda Shurer said her husband, who was diagnosed with cancer three years ago, died Thursday, May 14, 2020, in a Washington, DC, hospital at age 41. AP file photo by Evan Vucci.

As I walked down the line, I saw two graves side by side. Green Beret and Medal of Honor Recipient Ronald Shurer II, who died from lung cancer, and U.S. Navy SEAL Scott Stout, who died from brain cancer. A few graves down are U.S. Air Force veteran Kelly Murray and Navy SEAL Zachary Miller II; both also killed by brain cancer.

Then there’s Special Forces operator Parry Baer, and to his left, former Secretary of State Colin Powell, both men occupied war-hardened bodies during their lives that were riddled with cancer when they died.

On Wednesday, May 31, 2023, Arlington received two more of our nation’s heroes who succumbed to cancer: Marine Aviator Col. Douglas Sean DeWolfe and Air Force Master Sgt. Samuel Soto.

In August 2021, the United States Army moved forward with plans to limit in-ground burials at Arlington because the cemetery is simply running out of space. Now, despite being largely removed from active war and large-scale engagements, our veteran cemeteries across the country are still being filled at an alarming rate — sometimes, the burial process can take months. The answer isn't to find more space to bury our service members, but to find out why they're dying — and help put a stop to it.

“On Memorial Day, I sat at my desk coordinating care for a 27-year-old Air Force veteran with a terminal diagnosis. I paid the co-payments of a 41-year-old Afghanistan veteran and new father battling colon cancer. I coordinated treatment with our partners at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston for a MARSOC Raider who was recently diagnosed with stage-IV pancreatic cancer.”

So often, we get stuck in a cycle of response. We put out fires; we deal with emergencies.

In 2002, according to data in a HIPPA-protected Department of Defense database, there was a 229% increase in active-duty cancer diagnoses. When you spend years responding to problems, it’s easy to fall into the rhythm of fixing them instead of focusing on prevention. In this case, that means fixing the system that caused the problems in the first place. That sluggish response to this dramatic spike in military cancer rates came in the form of the PACT Act.

Many post-9/11 veterans were exposed to a wide array of toxic substances and physiological stressors, most notably airborne/environmental pollutants from open burn pits, but also by way of combat engagements, blast exposures, and toxic munitions.

It has been almost a year since the most significant piece of legislation regarding military veterans, the VA PACT Act, passed into law. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) PACT Act Dashboard, more than 250,000 PACT Act-related disability benefits claims have been completed.

The program has also seen the enrollment of more than 84,000 veterans and has helped conduct 3.4 million toxic exposure screenings with 42% endorsing at least one potentially toxic exposure while in service. The screening includes a three-question exposure questionnaire:

- Do you believe you experienced any toxic exposures, such as Open Burn Pits/Airborne Hazards, Gulf War-related exposures, Agent Orange, radiation, contaminated water at Camp Lejeune, or other such exposures while serving in the Armed Forces?

- If Yes, do you believe you were exposed to any of the following while serving in the Armed Forces: Open burn pits / Airborne hazards, Gulf War-related exposures, Agent Orange, Radiation, Contaminated water at Camp Lejeune, or other exposures?

- Does the Veteran or Caregiver have follow-up questions?

The PACT dashboard, which is updated biweekly, shows how much work the VA has done to care for our military veterans and families. It highlights claims milestones and benefit-related accomplishments. It’s a visual representation of the sincere, hard-working, and dedicated efforts of the VA — but is also reactive because, by law, they don’t have a choice.

I tend to have a “boots on the ground” approach to veteran health, especially when compared to those creating and relaying the rules and regulations. But when asked about the health outcomes concerning the toxic exposure screening of over 3.4 million veterans, the Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs stumbled on his words. He ultimately said that they do not track health outcomes. The most significant piece of veteran health-related legislation in history isn’t tracking health outcomes.

Sgt. Robert B. Brown from Fayetteville, North Carolina, with Regimental Combat Team 6, Combat Camera Unit, watches the civilian firefighters at the burn pit as smoke and flames rise into the night sky on May 25, 2007. Camp Fallujah has its own civilian-run fire department to assist the Marines and soldiers during a fire or emergency. US Marine Corps photo by Cpl. Samuel D. Corum.

Most people in government leadership positions tend to favor this reactive effort and display of success because it is more “tangible”; downstream work is easier to see. But the most critical component behind all of these numbers is the actual veterans. They are still sick, still in a chronic state of illness that we are now compensating.

Wouldn’t it have been easier, more cost-efficient, and in the best interest of the veteran to prevent this condition or diagnosis in the first place?

You would think 20 years of “downstream rescuing,” as evidenced by preventable cancer deaths, survivor benefits payout, and lack of burial grounds in our nation’s largest military and veteran cemetery, would enact some upstream changes.

So why hasn’t it happened?

This Dec. 16, 2014, photo shows the wedding photo of Army widow Aimee Wriglesworth and her late husband, Chad, on display in her home in Bristow, Virginia. The couple married when Chad was in the Air Force; he later transferred to the Army, where he rose to the rank of major. Wriglesworth lost her husband to cancer in 2013. AP photo by Steve Helber).

Downstream efforts are narrow, fast, and tangible. They address chronic problems that are often difficult to treat, like late-stage cancer. Like the PACT Act Dashboard, you can see rapid, measurable outcomes with these types of initiatives. You can see that 42% of the 3.4 million screened were deemed at-risk for exposure to toxins, but it ends there — no secondary screenings for specialized referrals, no follow-up on symptomology. Nothing.

Upstream approaches are more desirable, but they can also be more complex and ambiguous and consist of things like primary prevention through education, and secondary prevention like cancer screenings for early identification, which can results in cancer that is more easily treated if caught early.

If fewer people are getting sick, there is less need for disability benefits.

In a 2018 U.S. News article, Rebecca Onie and Rocco Perla, co-founders of The Health Initiative, discussed a focus group they conducted that asked various groups of people, both Democrats and Republicans of all ethnicities, “If you had $100, how would you spend it to buy health in your community?”

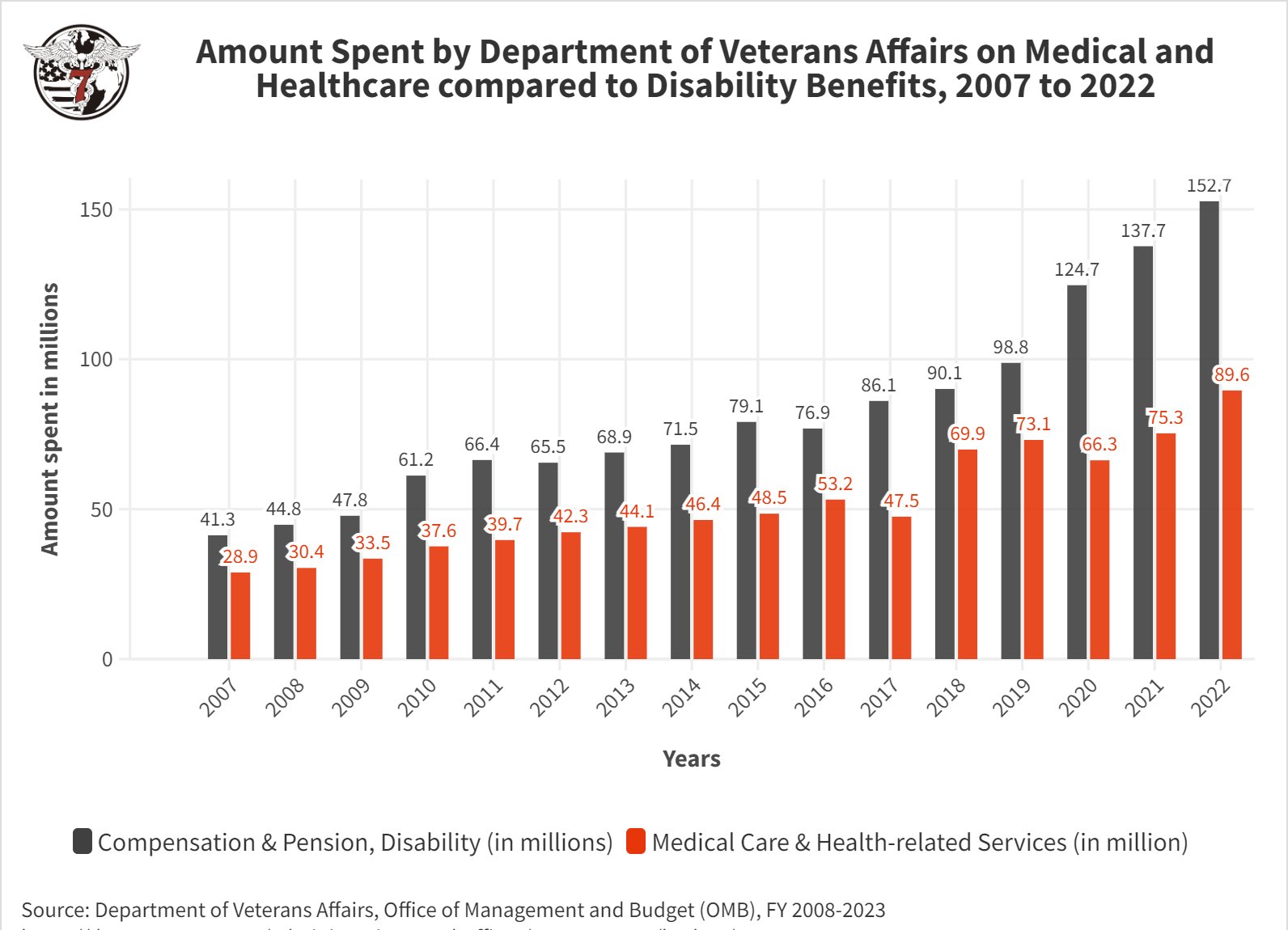

Every group said nearly the same thing: For every $1 spent on downstream health care, most thought it was wise to pay $2 upstream. That ratio is similar globally across developed countries, with one major exception: the United States. For every $1 spent downstream, we spend nearly $1 upstream. However, for the Department of Veterans Affairs, for every $3 spent on disability benefits and compensation, we spend $1 in actual healthcare — and mere cents in upstream initiatives.

What is distinct about healthcare spending in the US isn’t how much we spend but what we spend it on. We spend more money fixing people’s chronic ailments than keeping them healthy. Compound that by what we spend within the Department of Veterans Affairs, financially, at best, is a 4:1 ratio. No wonder so many veterans are sick and dying.

On Memorial Day, I sat at my desk coordinating care for a 27-year-old Air Force veteran with a terminal diagnosis. I paid the co-payments of a 41-year-old Afghanistan veteran and new father battling colon cancer. I coordinated treatment with our partners at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston for a MARSOC Raider who was recently diagnosed with stage-IV pancreatic cancer.

“Since the start of 2023, we can confirm the cancer-related deaths of 108 post-9/11 military service members and veterans; that is roughly one (preventable) cancer death of a post-9/11 warfighter every 30 hours.”

I also wrote a letter of nexus for the family of Army Ranger Matt Small, who died from peritoneal mesothelioma days after his child was born. And I ended the day by ordering thousands of dollars worth of multi-cancer early detection tests to screen at-risk, symptomatic military veterans for 50 types of cancers using two tubes of blood — with funding that we do not have. Memorial Day, to our team, is just like every other day.

Politically speaking, Memorial Day outings seem more like virtue-signaling and victory laps defended by “problem blindness.” When we don’t see a problem, we don’t have to solve it. And that passive blindness — that willful ignorance — will lead to enormous harm. It already has. And it’s as much a political phenomenon as a clinical one. Look at the negotiations on the debt ceiling; this endless debate carries weight because once something is identified as a “problem,” it requires a solution, and it creates an obligation.

Instead, our government is pitting veterans against each other. Remember when concerns of “Republicans allowing cuts in veterans benefits by 22%” caused an uproar of anger and fear based on fabricated situations with no supporting evidence? With such a concrete number of 22%, we’d assume that there would be data to support the claim.

This photo of Sgt. First Class Matthew David Small was shared on Small's memorial page. The US Army Ranger died March 14, 2023, after being diagnosed with metastatic mesothelioma.

HunterSeven asked the Executive Office of the President and received a letter in return stating that it isn’t their job. How can we trust those in charge of health care laws when they can’t accurately relay data?

Since the start of 2023, we can confirm the cancer-related deaths of 108 post-9/11 military service members and veterans; that is roughly one (preventable) cancer death of a post-9/11 warfighter every 30 hours.

Rare brain cancers, breast, and pancreatic cancers — cancers we would never expect to occur in a young, otherwise healthy population — are common among this subset of Americans. Some of these service members are not even old enough to drink alcohol, such as Marine Lance Cpl. Gabriel Puchalla, while others live only a month, at best, between diagnosis and death, like 30-year-old Army Staff Sgt. Melvin Tamfu, who died of liver cancer, or 33-year-old Navy Seabee Melissa Hathaway, who died of breast cancer.

And these deaths are just the ones we know about.

Chelsey Simoni is a disabled veteran, emergency/trauma advanced practice nurse specializing in public health, case management, toxicology, and infectious diseases. Chelsey is the co-founder of the HunterSeven Foundation and the principal research author of various groundbreaking publications surrounding post-9/11 military veteran health and wellness, including “A Pilot Study of Airborne Hazards and Other Toxic Exposures in Iraq War Veterans.” She is a doctoral candidate focused on creating artificial intelligence and machine learning models to predict cancer based on exposures in those who serve in the military.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.