Utopian Dreaming in Seattle’s Autonomous Zone: My Weekend Inside the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest

Seattle Autonomous Zone CHAZ Photo by Ethan E. Rocke Coffee or Die Magazine

I had seen the Fox News report June 10: “Seattle helpless as armed guards patrol anarchists’ ‘autonomous zone,’ shake down businesses.” Above the headline, superimposed on a banner image of a protester running past burning cars and buildings, was the all-caps label: CRAZY TOWN.

Fox News later admitted the image was an Associated Press photo taken May 30 in St. Paul, Minnesota. And also they Photoshopped several wire-service photos together, mashing up images of an armored, AR-15-carrying leftist with more chaotic scenes. Apparently, sometimes you accidentally manipulate wire photos to support a particular narrative. It’s not like they intended to consciously produce and distribute propaganda. Have they fired the intern?

Four days after protesters took over Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct and established an “autonomous zone” in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, I drove up to see for myself what was happening there.

June 12, 2020

It’s about a three-hour drive from my home in suburban Portland, Oregon, to Seattle. As I cross the Columbia River and the Oregon-Washington border, I dial up a veteran buddy who worked in law enforcement for a long time and sometimes spends too much time in the dark corners of the internet, perhaps because the stuff that goes on there is often more exciting than whatever he’s got going on in real life.

This friend — let’s call him Will — is rural, religious, and ready for the Boogaloo. As I tell him I’m going to see what’s really happening in Seattle, my subtle implication is that maybe he should take a break from his steady diet of right-wing propaganda.

“I don’t want to say too much,” Will tells me. “But the biker gangs are monitoring the situation up there.”

“Oh yeah?” I reply.

“Yep. The Hell’s Angels and other gangs are very well organized, and they’re keeping an eye on things.”

The last time I visited Will, I noticed his QAnon coffee mug. “THE STORM IS HERE, Q Anon,” it read below a black-and-white image of a weathered American flag with a skull wearing an American-flag face mask floating over it. QAnon started as a post on 4Chan and has grown into something like a new religion.

Will is also a vocal critic of the stay-at-home orders that governors all over the country imposed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. He’s sent me more than one dubiously sourced internet video promoting (roughly) the idea that COVID-19 is a hoax manufactured by Bill Gates and his reptilian-plutocrat cronies to force everyone in the world to be vaccinated against their will, micro-chipped, and forced to live under a new world order of socialist tyranny. Apparently, Gates — who has Scrooge McDuck levels of wealth — wants to expand his already vast fortune by trapping all the world’s free peoples under an inescapable, global surveillance state.

Whatever you do, don’t tell these people about cell phones and how many times the Patriot Act has been renewed.

Jonathan Gottschall is an American literary scholar who specializes in literature and evolution. In his book “The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human,” Gottschall discusses how the human need to impose a useful narrative structure on the world is an adaptive trait that sometimes leads to the formation of conspiracy theories.

“Conspiracy theorists connect real data points and imagined data points into a coherent, emotionally satisfying version of reality,” Gottschall writes. “Conspiracy theories exert a powerful hold on the human imagination.”

Will’s coffee mug warns, “THE STORM IS HERE.” And as I drive north on the I-5, I can see what looks like dark clouds gathering on the horizon.

When I enter the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, or CHAZ, the first thing I notice is the ubiquity of “No photos” signs. I see one posted on what appears to be an aid station.

“Hey, no photos please, no recording, thank you,” a woman tells me curtly, waving her hand disapprovingly like I’m a student in her preschool class. Save the white helmet, she’s dressed in all black, wearing knee pads, sturdy boots, and some kind of utility belt. She looks like an extra in a low-budget dystopian film.

Everything I know about communications law tells me I’m within my rights to photograph anyone and everyone in this public space, but I immediately get the feeling I’m not in Kansas anymore. The CHAZ protestors have dropped a house on America’s social contract in hopes of building a new world with enough ruby slippers for everyone. Naturally, I wonder who’s deciding what is and isn’t photographable in Oz. I wonder what they’re afraid people will see here.

“No photos” is actually a tremendous ask of a photojournalist in this environment. In a few short days, the CHAZ has become a mecca for artists, activists, and anyone looking to coalesce around the common causes of social and racial justice. An explosion of creativity has blanketed the streets and buildings in a visual feast of vibrant colors and inspired art. The ceaseless colors and level of skill I see in the artwork all around reminds me of “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” (which is unequivocally the best Spider-Man film, animated or not).

Three people wearing fluorescent-green hats catch my attention. “National Lawyers Guild Legal Observers,” their hats read. I approach and ask if I can ask them some questions on camera. A brown-haired woman wearing sunglasses and a watermelon-patterned face mask agrees to speak with me.

“We’re lawyers and people in the legal profession who are here to observe interactions between the public and protestors,” she tells me. “Also law enforcement officers and the protestors.”

Before I can ask follow-up questions, my friend Chris — an energetic Southern ginger with a Leprechaun-meets-Grizzly-Adams pandemic beard — pipes in from my right shoulder and starts grilling the woman, demanding to know who she’s representing and who invited her here. Chris is a veteran buddy and lawyer who volunteered to watch my back in the CHAZ.

The woman quickly decides she no longer wants to speak with us. I thank her for her time, walk away, and then explain to Chris why he should never do that again.

“When you’re a journalist reporting the news, you generally should not immediately pick a fight with the people from whom you’re trying to get information,” I explain. “We’re not here to judge people; we’re here to observe, ask questions, and learn.”

We move to the intersection of 10th and Pine Street where a massive Black Lives Matter street mural begins. People sit and kneel at the top of the “L” above an image of a beautiful Black woman. They raise fists and smile behind masks as loved ones take smartphone pics.

Moving toward the East Precinct, I see about a half-dozen protesters on the rooftop. As the evening sun paints a thin highlight on their right sides, some of them have an “I’m the king of the world” look while others stoically scan the streets below. A line has formed by the building’s fire escape, and people are ascending and descending, helping each other along the way.

As I record the scene, a masked white man leans toward me and says, “You should get up there. That’s where the good shots are.”

Something about his monotone voice puts me on edge.

“Yeah, I should probably get up there,” I say, trying to make eye contact. “Probably some great shots.”

He nods lazily and says, “Yeah, dude.”

We are cool.

I’m drawn to a massive shrine paying tribute to George Floyd and others killed by police. Messages are scrawled everywhere:

“Mourn the dead and fight like hell for the living”

“Communal grief is an act of solidarity”

“Abolish the police”

“Rest in power”

“Amnesty for all looters, rioters, protestors”

A crowd hovers, and people take turns lighting candles, dropping flowers or artwork, praying, taking photos and video. Off to my right, a dark-haired fair-skinned woman wearing a surgical mask and glasses sits on her heels, tightly clasping a set of rosary beads. She prays silently, her eyes shut tight, seemingly unaware of the world around her. She radiates intensity, like she’s trying to will herself into a cosmic conduit for empathy. Everyone gives her a wide berth, as if they too feel the gravity of her bubble.

Around the corner, a Black artist is setting up an exhibition on the sidewalk, hanging colorful, intricately detailed drawings on the building’s facade. The man seems to notice me filming, and he throws me a side-eye as he hangs a “No Photos” sign. I lower my camera and turn away.

Nearby, a man is selling Black Lives Matter T-shirts, which are fairly common throughout the CHAZ. Chris asks how much, and the dude tells him $80. Either there’s a price markup for white people, or this is just good old-fashioned price-gouging — the invisible hand of the free market doing its thing. When Chris returns the next day, he’ll lay on his Southern-lawyer drawl, talk the guy down to $20, and proudly rock a BLM T-shirt for the rest of his time in the city.

An attractive, 20-something white woman picking up trash catches my attention. She declines an on-camera interview but agrees to speak with me. “I just wanted to help out,” she tells me. Pointing to her trash picker, she says, “I just bought this thing for like $25, grabbed this bag, and started picking up trash.”

All over the CHAZ, people have shown up to help out however they can. There are stations all over the roughly six-block area where anyone can grab free snacks, bottles of water, and all kinds of useful items and necessities. The atmosphere feels similar to the finish line at a long-distance race, where volunteers and sponsors go out of their way to make you feel comfortable and welcome as they nourish you with free stuff. In a way, it’s all somewhat performative. People are here for the anarcho-communist cause, but I wonder how sustainable the scene is. I wonder to what extent these impulses and actions are truly “organic.”

Not far from a row of portable restrooms on Pine Street, there’s a hair salon whose bathroom is open to the public. Inside, a couple of employees lounge by a table full of free drinks and snacks.

“Can I use your bathroom?” I ask sheepishly.

“Absolutely,” says a man who looks like an ’80s synth-pop keyboardist. “It’s in the back to the right.” He smiles warmly, pointing the way.

I’m somewhat surprised to find the bathroom spotless. I make sure to leave it as I found it. Back in the salon, our keyboardist friend explains that the owner of the business used his own money to turn his salon into a communal pitstop.

“Then people just started donating and replenishing it on their own,” he tells us.

Chris and I each take a mini Twix bar and enjoy a free snack.

“Marxist Twix tastes just like capitalist Twix,” I quip.

Chris howls.

Back outside, I snap a frame of the “Interfaith Chaplain” table. A white woman wears a rainbow clergy stole draped over a “THIS PASTOR LOVES YOU” shirt and blue jeans. Her eyes smile at me from above her surgical mask. Next to her stands a white man wearing a purple stole and a ninja-like face covering above a white clerical collar. “Black Lives Matter,” reads the purple sign taped to the table in front of him. Behind him, a collage of colorful artwork connects to a black-and-white George Floyd mural. Visible on the wall behind the man and woman is a dialogue bubble that reads, “Change is in the wind.” The scene looks and feels surreal, as if I’ve walked inside a comic-book.

I notice the tiny pink-and-blue striped flag on the chaplain sign and easily recognize the Trans Pride Flag. It’s the same flag my gender-fluid daughter, Sam, kept proudly waving at a pride celebration in San Francisco last summer while wearing a Pansexual Pride Flag as a cape. The vibe in the CHAZ today feels very similar to Sam’s boundless positive energy that day.

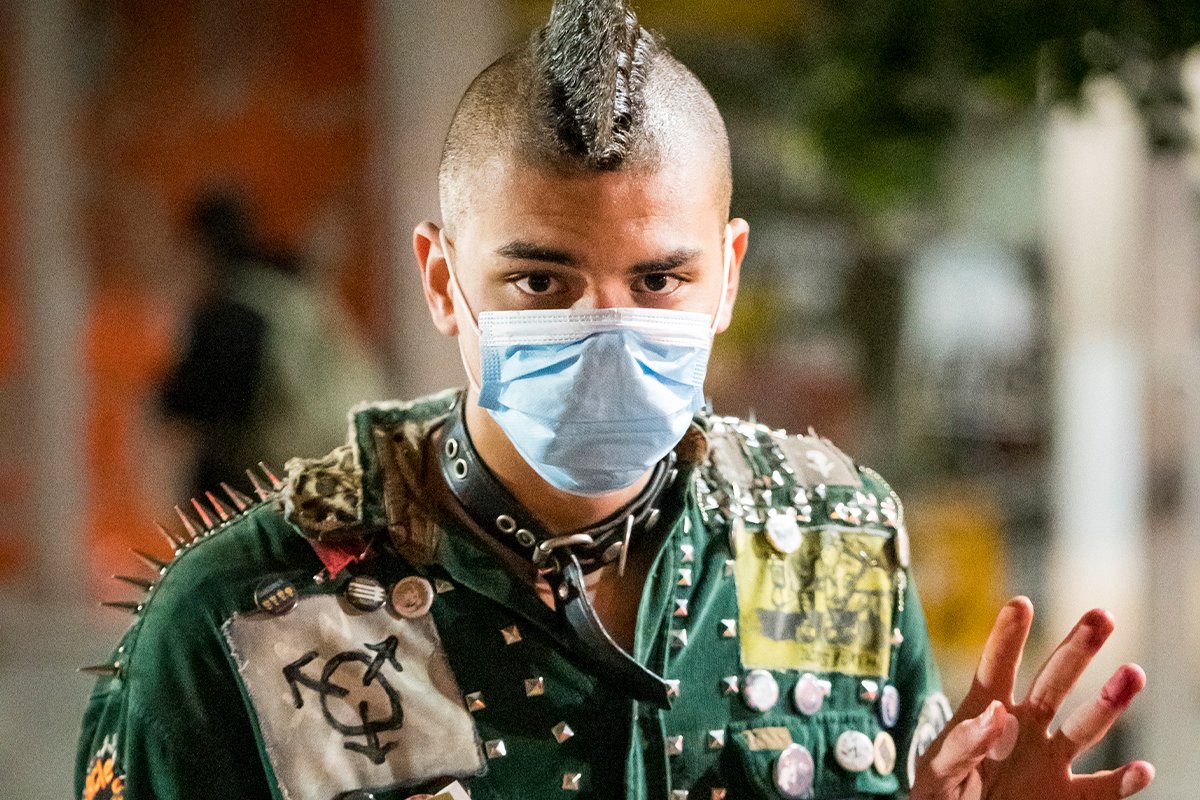

June is Pride Month, and Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood has a strong LGBT culture. The CHAZ is full of LGBT people. Flags celebrating pride of all types are everywhere. I snap a photo of a large trans person whose T-shirt reads “Arm Trans People. Disarm Cops.” They’re wearing black cargo pants, a radio, a pack, a utility kit on their hip, a tie-dyed face mask, stylish eyeglasses, and gaudy-yet-fabulous dangly earrings. A rainbow flag and a Trans Pride Flag poke out from their pack. A pair of binoculars plastered with a “FCK NZS” sticker hangs from a rainbow-colored sling at their side.

The person is one of many we’ve observed who appears to be part of a clandestine security force within the CHAZ. The kitted-out trans person looks like the type who would have been down for the cause during the Stonewall Uprising. You can trace pride’s origin to the Stonewall Inn, one of New York City’s most popular gay bars in 1969. While the CHAZ movement belongs firstly to the Black Lives Matter cause, Pride’s legacy and the Bohemian sensibilities of queer people make them allies in the fight against police brutality.

A 30-something Seattle native named Aton tells me the vibe in the CHAZ feels “very Seattle.”

“It feels somewhere in between, like, middle-school field day and Burning Man,” he says affectionately.

Another Seattle native, Tyr Symank, and his girlfriend, Nichole, round out my crew in the CHAZ. Tyr is a Washington National Guard soldier who helped secure the East Precinct in the early morning hours of June 8 before Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan ordered police to pull out of the area. Tyr, who is also a Black Rifle Coffee Company employee and a seasoned combat veteran, has a quiet-professional quality.

“All we had was body armor and sticks,” he tells me, stoically recalling how he and his Guardsmen weren’t issued any firearms for the mission, a fact he says was probably for the best, even if it left him and his soldiers feeling somewhat vulnerable.

Tyr told me he and his soldiers “never had to lay hands on anyone” as they helped Seattle bike cops disperse protesters enough to move in and clear away a barricade of dumpsters that had been chained together. One protestor, surprised and seemingly terrified by the charging phalanx of motor bikes and baton-wielding Guardsmen, found himself suddenly pinned in by dumpsters, cops, and soldiers.

“He just threw his hands up like, ‘What do you want me to do?’” Tyr recalled, his thick mustache curling up with a gentle Ron-Swanson-like smile. “We were like, ‘Get the fuck out of here, man.’”

After talking to Aton, Nichole mentions how strange it feels to be out in public again.

My mind wanders briefly to the sign I saw while covering the protests in Portland on June 7: “Sex is great, but have you ever fucked the system?” It seemed to contain some poignant social commentary on the extent to which the popularity and potency of the protests has been amplified by the collective emotional trauma wrought by the pandemic. After months of mundanity and idleness, people are feeling good about having a purpose again, especially one whose stakes are so high. A fight for America’s soul is happening right now, and for a lot of folks, that’s better than sex.

As we make our way to Cal Anderson Park — a turf baseball field inside the CHAZ — the sun has dipped below the horizon, and the field’s lights illuminate the area. In the park, the Burning Man vibe intensifies.

There are “Rejuvenation Stations” where volunteers give away free food, water, masks, hand sanitizer, and other medical supplies.

As I film, a man who looks like he’s maybe taken one too many acid trips has decided to become the star of whatever film I’m making. He hams like a toddler, dancing close and sticking his tongue out at me, crossing his eyes and generally losing himself in that way people who have checked out to a higher plane often will.

Upbeat ’90s hip-hop vibrates across the artificial-turf baseball field, animating patchy clusters of masked, mostly young people who dance or lounge around with loved ones and pets. There are cute dogs everywhere. The air is fresh and cool. Clouds of smoke plume up and dissipate here and there, and the smell of Washington weed cuts the air. Two bros dance together, attempting their best Kid ‘n’ Play foot-touch dance. Behind them, several young women dance and play with hula hoops. People are blowing bubbles, smiling, and laughing.

After a solo lap around the park, I link back up with Chris, Tyr, and Nichole.

I look at my entourage, and all of them seem to be infected by the blissfulness surrounding us. They look slightly awestruck.

“This is why I wanted to come down here,” Tyr says. “I knew there was a lot of propaganda coming out of here, and I wanted to see for myself what’s going on.”

Tyr and I had already discussed how the CHAZ and the general civil unrest sparked by George Floyd’s death are ripe targets for exploitation by foreign adversaries. In March, the New York Times reported that Russia is engaged in influence operations to inflame racial tensions in the United States, “including trying to incite violence by white supremacist groups and to stoke anger among African-Americans.”

“This is not what I was expecting — at all,” Chris says jovially.

Nichole just shakes her head and smiles. “Nope.”

It’s almost 9:30 PM. All of us are high on the park’s Utopian vibrations, but we’re hungry, too. We leave the CHAZ and head up Broadway, which Tyr explains was made famous in Sir Mix-a-Lot’s “My Posse’s on Broadway.”

It’s late, and COVID-19 restrictions make it especially challenging to find an open spot to eat. We hit up a QFC grocery and buy beer, cider, and snacks before finding an oasis of a Mediterranean fast food joint. We take up two tables in the back corner of the establishment and proceed to absolutely wreck the gluttonous orgy of exquisite craft beers and ciders, delicious gyros, garlicky-feta fries, salad, and more. We raise cans and bottles to new friends and to being with people in public for the first time in too long.

When we are full and well buzzed, we venture back inside the CHAZ, where the party continues. Young people try to scale the facade of a now significantly graffitied landmark next to the Lincoln Reservoir, clumsily failing to make it up a rope someone has rigged.

Nearby an irregular-cone-shaped brick structure juts from the ground, and kids sit on its flat peak. Protesters have tagged the site with the words, “Kill the masters.” The phrase is taken from “Game of Thrones,” and while the character who speaks it does (kind of) free a slave army and kill their masters, she ultimately can’t let go of inherited and lived trauma, so she decides to literally burn the world down and reduce it to ash. The meme feels all too appropriate.

We walk through the park and get back to the heart of the CHAZ. There’s a basketball court where people are playing pickup ball nonstop.

About a block away, we hear people yelling, “He’s got a knife!” I run toward the scene and find a scruffy-looking middle-aged white dude wearing a yellow “Liberty or Death” towel like it’s a superhero cape. He’s vaguely threatening a person in all-black with a backpack who, I assume, is also part of the security force. Liberty or Death waves his tiny foldout utility knife and grunts some noises like, “Stay back. Go away.” But the security guy just calmly and patiently corrals the guy out of the CHAZ.

Situation defused. It’s time to call it a night. We walk back to my hotel, trade hugs all around, and say goodbyes.

JUNE 13, 2020

On my second day in the CHAZ, I learn protesters have decided to rebrand it as the CHOP, or Capitol Hill Occupied Protest. The change seems superfluous — ill-advised even. CHAZ has a nice ring to it, and “autonomous” is a softer word than “occupied,” which invokes images of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Wall Street — generally rudderless quagmires of vaguely defined strategic objectives.

My day starts early Saturday evening at the corner of 11th and Pike Street. Chris and I approach the barricade and the roughly half-dozen men and women who appear to be on watch there, letting cars in and out. I ask if I can record them.

“No. And thanks for asking though,” says a thin, middle-aged white man who calls himself JJ. He’s wearing a black mask, sunglasses, a radio with earpiece, a Seattle Sounders jersey over a bulletproof vest, a backpack, and very skinny jeans.

JJ and a 20-something white man who says his name is Francis agree to speak to me off camera. JJ talks a lot — and fast. Chris and I wonder if he is the naturally energetic type or if his mood might be chemically enhanced. Eventually, I hear JJ and Francis confirm what I had hoped to hear.

“Of course we have people carrying concealed weapons here,” Francis says. “We’re a shall-issue state, which means if you apply for a license to carry concealed, the state has to give it to you as long as you don’t have a felony and can pass a background check.”

I ask what kind of experience, training, or certifications their security personnel have.

“We don’t require any special certifications or training for anyone here, except our paramedics, EMTs, and medical personnel,” JJ says.

I’m struck by the realization that the far-left protesters I’m talking to seem to be on the same page philosophically with a lot of pro-gun activists on the right who oppose most if not all gun-control regulations.

JJ and Francis tell me that while there are many people inside the CHOP who are ideologically opposed to guns, they are necessary for keeping the CHOP safe and secure.

Not far from us a sign reads, “In a world without cops, we must never again become the cops ourselves.”

I wonder who the “we” and “us” the security guards keep referencing are. The nebulous and amorphous nature of this movement and its purported commitment to horizontal governance make it extremely difficult to identify leaders, policy objectives, and the structure and scale of the movement’s political organization.

“The group that we’re a part of, which I’m not going to name, has a lot of military veterans and former law enforcement who have gone more left since leaving the service,” JJ tells me.

Most of the so-called “safety awareness guards” I see in the CHOP are white, and I wonder if anyone plans to address the lack of representation among this community’s guardian class.

JJ gets a call on his radio and tells me, “We’ve got a bit of a situation we’ve got to attend to.”

He and Francis take off running into the CHOP, and Chris and I follow them two blocks north. As we turn the corner onto Pine Street, a person dressed in all black blows past me carrying a wadded up American flag. I fumble with my camera, rushing to start recording, but the person is gone in a flash. I move toward the commotion in front of the East Precinct and start my camera recording.

A crowd has formed around a light-skinned Black man in cutoff jean shorts and his two white allies — a stocky young guy in a Yankees jersey and American flag headband and a fit blond woman with an American flag face covering. They are carrying an American flag mounted on a massive tree-branch flagpole into the CHOP. They appear to be right-wing counterprotesters.

As the crowd encircles the rightists, a Black man yells desperately, “Don’t do nothing! We’re gonna be on Fox News looking dumb as shit if we do something to them! Don’t do nothing! Let them stand there looking stupid as shit and move on!”

While the crowd surrounds and harasses the three rightists, no one attacks them. As some Black Lives Matter protesters and journalists try to talk with the trio, the crowd plays loud siren noises, and a young Black man with long dreads yells repeatedly over a megaphone, “Are you proud to be Black, race traitor?!”

A beautiful young Black woman grabs the megaphone and says over and over, “Camera phones down. You’re just giving them a platform.”

I see a sea of smartphones go down as I keep shooting video with my Nikon Z6. The woman focuses her energy on those of us still shooting.

“The white ally in the yellow hat, please put your camera phone down,” she says.

There’s no mistaking who she means. A good chunk of the crowd has honed in on the young white woman filming with her smartphone. She and I make eye contact briefly and share a smile that seems to say, “Nah.”

“Thank you to the people who are listening and not just being a performative ally,” the Black woman says, trying to shame us. “Thank you to the people actually listening.”

“You’re feeding into it with your cameras!” a man yells. “Listen to her!”

There must be at least two dozen cameras or camera phones recording the scene. The “de-platforming” strategy fails.

Someone yells, “Cameras down; push him out!” Agitators start pushing, but people close to the flag carrier protect him from the aggressors. The soft-spoken, bespectacled Black man, who looks like a roadie for Lynyrd Skynyrd, tells a journalist he’s not with the Proud Boys or representing any right-wing group or affiliation. When people ask who he’s with, he stoically responds, “America.” The journalist asks, “What would you like to see happen here?” And the man responds with a smile, “Middle ground, common ground, peace — just as everybody wants.”

I struggle mightily to understand why so many people in the crowd are apoplectic over three people carrying American flags, apparently representing no cause other than their right to walk through the CHOP carrying American flags.

“I remember when all Americans were anti-fascists,” someone yells. “Remember World War II?” People cheer, apparently not grasping the irony of their efforts to prevent an American veteran from flying a flag in their community.

The rightists walk toward the park’s northern edge with the swarm of people hovering. A Black man in an “I Can’t Breathe” shirt hovers on the blond woman’s shoulder, asking, “You don’t like that freedom of speech?” and pointing to a megaphone behind him from which the “phones down” woman is blaring loud, tinny music.

The blond woman says something, and a protester yells, “Shut the fuck up, alt-right Barbie! Nobody gives a fuck what you have to say!”

A man grabs the megaphone and asks the Black rightist, “Ay bro, what does that flag mean to you?”

“Story. It’s a long story,” the man calmly replies.

“Are you a vet?

“Yes.”

“Were you killing people that look just like you?”

“No.”

“No? That’s who you’re representing — the guys who killed the guys who look just like you? Why are we marching with this shit? Can’t we do better? Do we need that fucking flag still?”

As we reach the park’s edge, a protester tries to rip the flag away, and after a brief struggle, Yankees-jersey secures the flag. He and the blond woman furl the flag around the branch and walk the rest of the way out of the CHOP cradling the flagpole at their sides. Protesters follow them well outside the CHOP’s boundary, and the woman says, “Quit following us.”

A protester says, “Put all that shit down and take off. Get the fuck outta here.”

Yankees-jersey stops and says, “Okay, we’ll give you the stick; just let me take the flag. If you take the flag, I will beat your ass.”

After detaching the flag from the branch, the rightists start running, and the protesters chase them for several blocks until they’re out of sight. I catch my breath with a small group that’s gathered on a street corner a few blocks outside the CHOP.

A stocky, ginger-bearded man in a camo-patterned hoodie who identifies himself as an 18-year-veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps pulls out a cigarette and starts talking to another man who says he’s a vet.

“No matter what streets they block off, no matter who says they’re in control, that’s still America,” says the Marine. “There’s a lot of men, especially of color, that died defending that flag.”

I call Chris, and he tells me to get back to 12th and Pine where a “people’s assembly” is happening in front of the East Precinct.

When I arrive on scene, a Black woman is speaking to a mostly white crowd through a megaphone. I find a spot to sit down about 25 feet from a small, covered stage in the intersection. I pull up my camera and start recording.

“They asked that everyone not take any photos or video,” says a young white woman with a camera to my left.

“Cool,” I say. “I’m a journalist.”

To my right, a young Black man sets three large pizzas on the ground in front of him and announces, “We have mushroom, cheese, and pepperoni.” A pink-haired white woman kneels down and says she’ll take whatever’s on top. The man, wearing rubber gloves and a surgical mask, hands her a piece of pepperoni. A hipster kid with glasses kneels nearby and asks for a piece of mushroom.

A middle-aged, bald Black man thanks the woman speaker and takes the megaphone.

“We don’t want nobody coming in here to hijack what we’re trying to get through,” says the man. “We don’t want the president. We don’t want the media. Whatever our message is, we don’t want nobody coming to try to hijack it.”

The crowd gives a round of applause, and I wonder if I’m somehow the only person who isn’t sure what specifically “the message” is.

A white man with long, brown hair and a brown blazer takes the megaphone and mentions that the organizers of the assembly have asked people not to film “for safety reasons.”

The man proposes “having some community agreements that we come up with as a community, so that we’re all on the same page — just something to, like, kind of centralize and just make sure we have the same aims and make sure we’re in this space for the same reasons, or similar reasons at least.”

It sounds a lot like he’s proposing some kind of formal charter or constitution whose authority and legitimacy is derived from the will of the people in a specific geographic location.

He continues, “And then have people at the barricades when you see someone new is coming in, just to kind of have a little conversation with them to make sure they’re on that page.”

The next speaker is a Black man with a friendly, professorial quality. He’s dressed in all black and a navy blue coat with a backpack and mask.

“All right, again, we had a request,” he begins. “This is a no-square zone. We’re logging off the internet right now. No cameras. I’m talking to you, sir, right in front of me.”

All around me, necks crane around, and eyes lock on me. Disapproving looks abound. I am now the other.

“Like, can I get a thumbs up or thumbs down?” the leader says. “No cameras, right? No cameras.”

Thumbs shoot up all around the crowd. A blond woman in a niqab-like face covering scowls at me as she holds up both thumbs. There’s probably a good joke about voter fraud to be made here, but it’s definitely not the time. Lady Two Thumbs stands up and makes her way toward me. I hear someone nearby say, “Turn the camera off!” I keep shooting as people close in and obstruct my camera’s lens.

“You want to be salty about it,” the speaker says. “All right, that’s cool. We can do that.”

Two Thumbs and others push my camera down and try to corral me back.

“Put it away,” Two Thumbs says sternly, pushing on my camera lens. “Put it away.”

“Can you stop touching my camera?” I say.

“Put it away. We’re asking you to put it away,” she says. “It was a democratic decision.”

“I’m a journalist,” I say.

“I don’t care,” she says indignantly. “It was a democratic decision. Put that shit away.”

A white kid puts a sign in front of my lens and says, “It’s what the group decided, homie.”

A middle-aged man says calmly, “We’ve asked very respectfully, sir. Please put it away.”

“Be a respectful journalist,” someone says.

“He’s not a journalist,” says a tall, black-clad white guy in a balaclava and backpack who looks like he’s part of the security force. “Journalists know when to walk away.”

“They know not to become part of the story,” says the other voice.

“He’s a provocateur,” security guy says menacingly.

From my point of view, the group, not me, just made the story about its lack of transparency.

At this point I’m surrounded and feeling very much like this is no longer a safe space. I have just gone from us to them. I have never seen the “tyranny of the majority” that James Madison famously warned against so poignantly illustrated.

I acquiesce, stop filming, and walk away from the scene, trying to put some distance between me and the mob. I pull up my phone and call Chris, who tells me he’s just on the other side of the assembly’s perimeter. I take my time circling around and find Chris. He tells me another leader spoke up in defense of transparency while I was away momentarily and that they’ve changed their minds on the no photos policy.

I lift up my camera and cautiously snap some photos of the crowd. The friendly professor who casually dispatched a mob to force my compliance is now asking the crowd if everyone will agree to not record or take photos again because he would like to discuss some “spicy tactics.” He appears to not get the response he’s hoping for and decides to put a pin in that topic.

Looking around the crowd, I see a couple of people with smartphones out. When a woman takes the stage and starts discussing a new proposal, I begin recording with my phone. A few seconds later, Mr. No True Journalist security guy stands up and grabs the megaphone.

“The guy that we asked to stop filming us is over there right now recording with his phone. This Richard-Spencer-haircut-looking motherfucker right here,” he says, pointing me out to the crowd.

I am deeply offended by the comparison.

The entire crowd is again staring at me contemptuously. I look to my left, and a long-haired dude on a BMX with a ball cap, thin mustache, and a half-baked look says with a hippie-stoner drawl, “Dude, you need to go.”

People all around me echo the sentiment.

“Let’s go, man,” I tell Chris. “It’s time to leave.”

We start walking away, and BMX guy and a few others shadow us up the block and out of the CHOP for good.

The CHOP is not the first anarcho-communist experiment in history. The Paris Commune is one of the most well-known examples. On March 18, 1871, radical socialist revolutionaries — mostly artisans, communists, laborers, and anarchists — took over the city of Paris. The occupation lasted 72 days before it was crushed in “The Bloody Week,” a brutal massacre that established France’s Third Republic.

Kristin Ross is a professor of comparative literature at New York University and the author of “Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune.” In an interview with Jacobin Magazine, Ross said, “The way people, particularly young people, live now resembles in its economic instability the situation of the nineteenth century workers and artisans who made the [Paris] Commune.”

Seattle’s CHOP came to a peaceful end June 24 when CHOP leaders declared an end to the autonomous zone experiment. The announcement came in the wake of multiple shootings inside the CHOP.

Before the CHOP was disbanded, protesters in Portland, Oregon; Asheville, North Carolina; and Washington, D.C., tried and failed to establish autonomous zones in those cities.

George Floyd’s death in police custody sparked nationwide protests against police brutality, but the people who have taken to the streets for more than a month straight are motivated by more than that singular cause. While racial justice is the movement’s foremost aim currently, the people supporting Black Lives Matter and the “defund the police” movement are a diverse crowd from all points on the political left. They are part of the strain of American leftism that fueled 2011’s Occupy Wall Street movement and 2016’s Dakota Access Pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. They are racial and social-justice warriors, climate activists, anti-fascists, #MeToo movers, LGBT activists, and all manner of disaffected or marginalized people who have coalesced around a loss of faith in American social and political institutions. Many are also privileged, middle-class white people who want to build a better world for all.

What is perhaps most concerning is that the same loss of faith in American institutions is happening simultaneously on the political right, where people like my friend Will rally around a collective sense of economic anxiety and cultural marginalization.

One person I met inside the CHOP put it like this: “It doesn’t matter what side of the train you’re on. It can be the left or the right. The train’s going to go off the cliff if nobody’s building new track for it. And I think that’s what we’re all trying to figure out right now.”

As an American with many friends and loved ones on both sides of the political spectrum, I worry constantly about our country’s trajectory. As politicians on both sides of the aisle exploit racial tribalism and cultural division, social media exploits and amplifies divisiveness, and moderate voices are drowned out.

Before I travelled to Seattle, I emailed former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis about the nationwide protests that were sweeping across the nation.

“I’m saddened beyond words for our nation and all our countrymen and women, especially those whose pain is palpable and wholly understandable,” Mattis wrote in his reply, which I received the night before I went to Seattle. “Yet I sense that this could turn into one of those moments when real change is initiated and the political will and friendships formed that will sustain that change. We’re building a country here, and it’s both noble work and hard work, but hard is no excuse for giving up. We must not just do our best; we must do the necessary to ‘bind up the nation’s wounds’ as President Lincoln put it so long ago. We should look on this as our opportunity to stand and deliver. Hang in there, stay decent even when others are not, and hold the line strongly until our nation recovers its respect and friendship for all our fellow citizens.”

I read Mattis’s words and wept. They felt like balm on a wound. For the first time in too long, I felt a glimmer of hope that we the people might still have it in us to heal our nation’s wounds and not only preserve this great republic but realize the full promise of our American dream.

Ethan E. Rocke is a contributor and former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine, a New York Times bestselling author, and award-winning photographer and filmmaker. He is a veteran of the US Army and Marine Corps. His work has been published in Maxim Magazine, American Legion Magazine, and many others. He is co-author of The Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper’s True Account of the Battle of Ramadi.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.