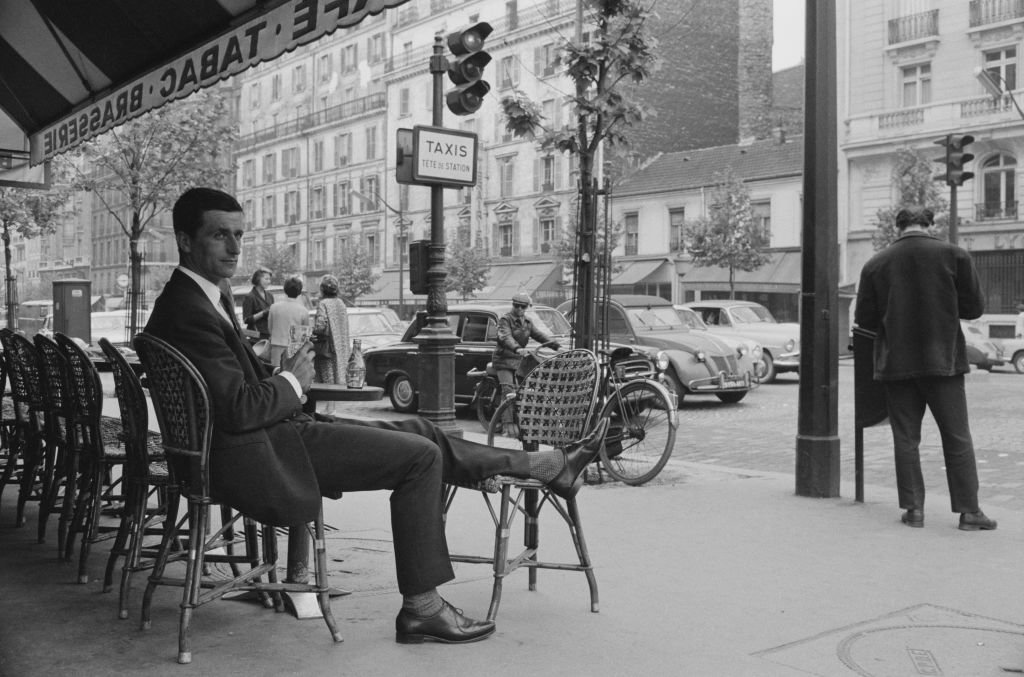

English professional cyclist Tom Simpson is seated outside a cafe brasserie in Paris, France, on May 29, 1963. Simpson has just won the 1963 Bordeaux-Paris classic cycle race. Photo by Stan Meagher/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

In the modern age of artisanal coffees and glossy-end machinery, it’s easy to get lost when thinking of the word “cafe.” The aroma of freshly brewed French Roast and the velvety feel of supple couch cushions floods the mind, but cafe culture is more than a simple pit stop for our daily cup of joe.

Cafes are structured around a few major components, two of the most prominent being the active sale of coffee and the people it draws in. Much like the deeply tangled web that is the coffee industry, cafes carefully balances the social, cultural, and economical motley that comes with both the beverage itself and the complications of being a public sanctuary.

Coffee may be the commodity that gave rise to the institution, but the population filing through the cafe doors provided the business its purpose. While American cafes saw their origins with the second wave of coffee starting in the mid-1960s, cafes have far deeper roots than Starbucks or a 20-year-old mom-and-pop shop.

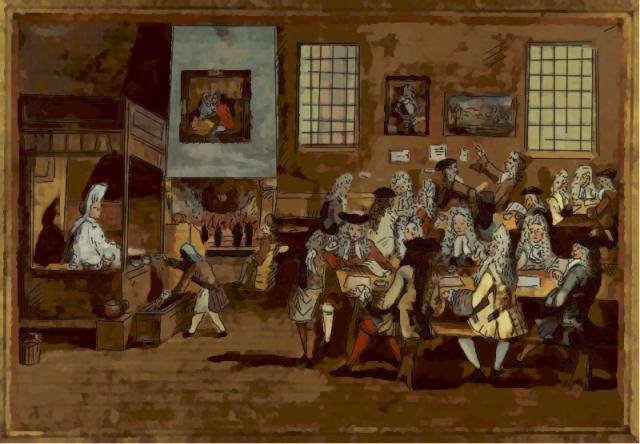

Cafes rose to prominence in Europe during the late 17th century as a result of their importance in the social sphere, as well as their ease of convenience. While restaurants and eateries specialized in meals, cafes minimized their selection in favor of providing patrons with coffee and affordable admission. This made it especially accessible to the working class to whom the establishments served as a retreat to foster community and promote the exchange of ideas and philosophy. Both a blessing and a curse, this age became known as the Age of Enlightenment.

While the local ale house provided many with the ability to converse, cafes remained a favorite confluence for the politically interested, specifically those who didn’t have the platform or means to voice their qualms elsewhere. Citizens upset by the upscaled pricing or legislations of their new regime could find solace in discussing these issues with their fellow cafe-goers. In an age of shifting ideologies and modest economic turmoil, British cafes gave the unheard a voice and the ability to debate and host intelligent conversation, which would have otherwise been drowned out beneath the authority of the elite.

Men from any social class could patronize the cafes; however, those in higher standing often avoided them for fear of losing status. They later regarded cafes as a nuisance. For forces of the upper echelon, cafes provided sanctum for their subjects and employees outside of their control, leaving room for the seeds of rebellion and change to be planted. This line of reasoning painted cafes as representations of equality and justice, something that earned them the attention and eventual wrath of King Charles II, who described the establishment as “a place where the disaffected met and spread scandalous reports concerning the conduct of His Majesty and his Ministers” in an attempt to discourage the congregation. His efforts were fruitless.

Cafes met their natural end following King Charles’ rule due to the increasing popularity of tea. However, British cafes bred a generation of activists, writers, and artists, setting the precedence for coffee house culture to come.

The social and economic position of coffee houses and cafes allowed for a meeting place receptive to all men regardless of occupation. This wasn’t true only in old Europe.

In the mid-20th century, Bogota, Colombia, featured several cafes across its sprawling cityscape. The prominent cafe culture was similar to London’s, laying the groundwork for intellectuals, activists, and artists to intersect. As the hub of a coffee-farming country, coffee was far from being exclusive to a coffee house. There were coffee bars, coffee clubs, even coffee pools. The drink aligned itself with secular values and helped bridge the intellectual and physical gap that might have otherwise separated men from various social standings. Much like British coffee houses, men frequented these cafes after finishing up at their office jobs, but it was also a hub that granted artists, journalists, and writers equity to the property, some doubling as galleries and convention centers. As in London, this attracted the attention of higher powers, to the Colombian cafes’ tragic detriment.

Beyond providing working-class men much-needed catharsis, coffee houses provided the general public with a method of unification and political revitalization that eventually deepened the divide between parties in what would become the Colombian conflict. With uprooted former militaristic powers colliding with some of the greatest minds of the generation, it was hardly a secret that cafes posed a very serious threat to Colombia’s already unstable government. When serious insurgency rose from the general public, the conflict brought about the end of the political coffee house.

France is another prime example of the political and social cafe. In the 1900s, Parisian cafes were hotbeds for thought, philosophy, and art, attracting the likes of Jean Cocteau, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In America, coffee houses were points of planning protests during the Vietnam War, a process later deemed “G.I. Cafes.” While the gravity of cafe culture has declined, they remain cultural incubators for artists and intellectuals.

In 1960s New York, coffee house culture was limited to Chock Full O’Nuts, a local chain that offered a modest cup of joe and a muffin on a good day, and a few mom-and-pop shops that managed to maintain integrity post-Depression. In 2020 America, the definition of “coffee house” has expanded.

The most recognizable modern cafes tend to be commercial chains that rose in response to coffee’s second wave. Unlike British cafes, which used its population to grant the cafe purpose, American cafes have benefited from the U.S. capitalist mentality. There is not one particular crowd associated with the American cafes — they are frequented by the well-dressed businessman on his way to work in the morning as often as the screenwriter set up to work at the espresso bar.

Modern cafe culture is tied inextricably to the coffee industry upon which it’s founded, and as coffee shifts, so does the American cafe. Rather than present a united front to engage in discussion across social standing, coffee houses have become specialized to attract a crowd based on the type of coffee they serve. This means the general business model has switched from one that’s community-based to one that’s commodity-based, which has helped revitalize the coffee industry as a whole.

Coffee is usually broken down into primary three waves. While the 1960s made the most use out of canned, pre-ground coffee to mark the first wave of coffee, the consequent waves have shifted from product to purpose.

From Seattle to Jacksonville, American cafes have come to resemble tree rings in terms of their longevity and style. Take Starbucks and Tim Hortons for example. Both chains rose to prominence to fulfill the need for specialty coffee beverages in the 1990s. This included a number of milky, espresso-based beverages. Second wave cafes, with their commercial gearing and national presence, have become synonymous with ease of access and mediocre coffee, as there is an inconsistent emphasis on the coffee’s quality. The crowd seeking these cafes not only desire the fancy coffee drinks, but also the convenience. Conveyor belt processes have made crafting these beverages efficient, if not particularly inexpensive. This is what brings in the businessmen, the students, and those generally in need of a quick fix.

This culture isn’t shared by cafe-goers of the third wave. With modernized methods of finding and sourcing quality coffee, third wave cafes emphasize the coffee itself. Its statement of purpose is to view coffee as “artisanal food” — much like wine — and the patrons reflect this line of thinking. Cafes such as Blue Bottle, Birch, and La Colombe offer quality beans to make premium coffee that doesn’t need to be loaded with milk and sugar to taste good. Unlike second-wave cafes that rely on seasonal flavors and marketing tactics to maintain a crowd, third-wave cafes use exclusivity as a means of maintaining their patrons’ interest. As such, third generations aren’t looking to expand their culture so much as they are trying to attract people with similar values and interests.

You will note that neither commercial-based wave caters to affordability, but this doesn’t stop either from being an attractive gathering place for writers, artists, and intellectuals. While cafe culture has grown and changed tremendously, the key mandates — coffee, company, and property — remain. With a variety of sourcing and the demand for high-quality coffee at the front of our country’s economy, don’t be surprised if coffee culture continues to shift in the years to come.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.