US soldiers at the Saipan air base in the Mariana Islands watch a B-29 Superfortress take off for an air raid on the Japanese mainland in December 1944. AP photo.

In early March 1945, hundreds of B-29 bomber crews were briefed on Operation Meetinghouse, a high-stakes mission to firebomb Tokyo, Japan, from their staging positions in the Mariana Islands. Commanding the mission was US Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, the aviation prodigy who had already led daring air raids over Germany and North Africa in World War II’s European Theater.

With a chest full of medals — a Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters, a Silver Star, and a host of other awards for heroism — LeMay’s mere presence demanded respect from the crews who stood before him quietly at attention. The general took a puff of the ever-present cigar resting on his lower lip. “You’re going to deliver the biggest firecracker the Japanese have ever seen.”

The confidence in LeMay’s voice wasn’t the put-on machismo that some practice in the mirror. It flowed from the staunch belief in a doctrine of strategic bombing that had crystallized over a decade through discourse with like-minded aviators who thought long-range heavy bombers could win wars. Alumni of the polarizing group, derided as the “Bomber Mafia,” include figures ranging from Robert Olds — the father of “triple ace” Air Force legend Robin Olds — to Jimmy Doolittle, as well as Curtis LeMay.

Related: Gladwell Book Explores Leaders, Tech, Morality of Bombing During World War II

Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, commander of the 21st Bomber Command, second from left, and Brig. Gen. Thomas Power, second from right, receive firsthand reports of a Superfortress raid on Nagoya, Japan, March 26, 1945. AP photo.

Curtis LeMay’s Early Years

Curtis Emerson LeMay was born on Nov. 15, 1906, in Columbus, Ohio, roughly 70 miles from the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop in Dayton and only three years after their famous first flight on the dunes of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. From his first day on earth, it was almost as if the boy was destined for flight.

But LeMay’s first encounter with an airplane didn’t come until he was 5. In his 1965 book, Mission With LeMay, the four-star general recalls an aircraft flying overhead. The young boy ran after the airborne vehicle, trying to catch it. Though the plane was out of reach that day, it wouldn’t be for long. The formative memory led to LeMay’s nearly 40-year career in a military cockpit.

Related: Legendary Fighter Pilot Robin Olds Was an Ace in Two Wars

One of only two airworthy B-29s flies over Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, on June 16, 2019. US Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Kayla White.

Up, Up, and Away

Although LeMay had long set his sights on flying full-time, his journey to active service in the US Army Air Corps — a predecessor of the United States Air Force — didn’t resemble checkers, but 4-dimensional underwater chess.

Because the Air Corps was rather small, few pilot slots were available in the active-duty Army, but LeMay was undeterred. He ping-ponged from ROTC to the Ohio National Guard for a slot at flight school and then back to the Reserves before finally earning his commission as a second lieutenant in the Army in 1930.

Securing an active slot at the 27th Pursuit Squadron in Selfridge Field, Michigan, was a rare achievement. There, LeMay flew single-seat fighters, including the Curtiss P-1 and P-6 Hawks, until 1937, when he was assigned to Langley Field, Virginia, just as Boeing delivered a dozen pre-production B-17s to the base for testing. Under the tutelage of the “Bomber Mafia,” LeMay fell hard for the doctrine of strategic bombing.

“Flying fighters is fun,” LeMay allegedly said later. “Flying bombers is important.”

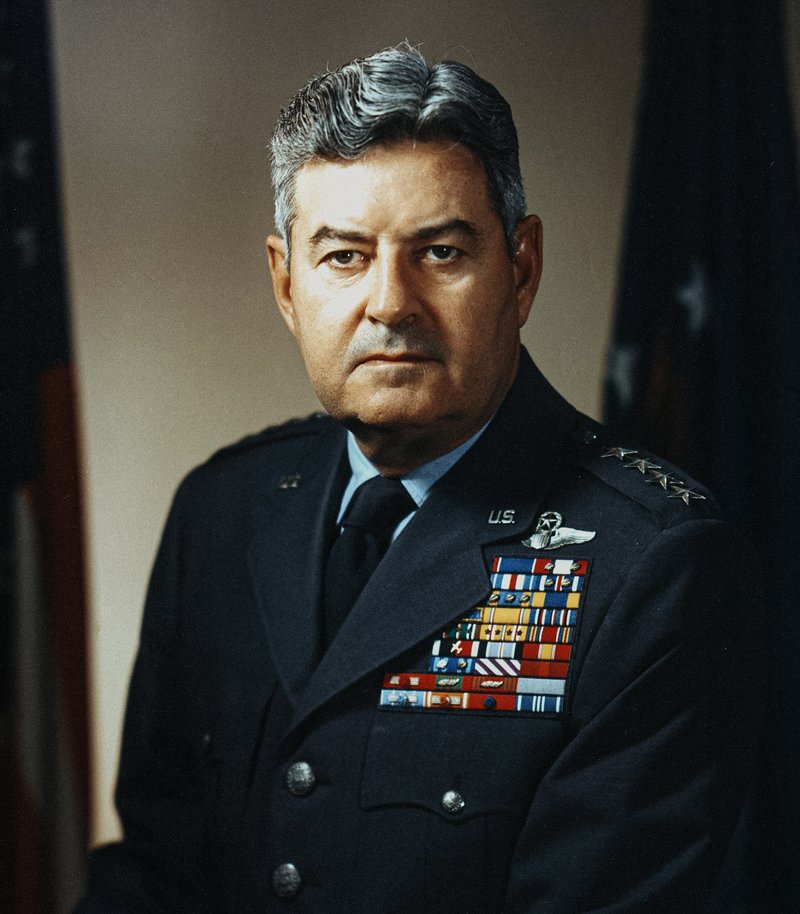

Portrait of Gen. Curtis LeMay. US Air Force photo.

Bombs Away LeMay

At Langley, LeMay became one of the first pilots to fly the B-17. He also learned to drop bombs as a bombardier and hone his aerial navigation skills in a series of flights demonstrating the value of America’s nascent heavy bomber fleet. Before GPS, navigation was a mentally taxing skill that required proficiency with an arsenal of gadgets, ranging from sextants, compasses, and protractors to celestial charts and radios, as well as gut-felt intuition.

Much to the chagrin of the Navy, LeMay took to navigation like it was second nature. In 1937, the Army’s new bombers participated in a training exercise with the USS Utah. Within 24 hours, the pre-production B-17s had to locate the Utah off the West Coast and “destroy” the battleship. But the Navy — who hadn’t been taking the Army’s bomber force seriously (as it turns out, inter-branch backbiting isn’t a modern invention) — rigged the exercise from day one.

Crew members from the Commemorative Air Force prepare a B-17 Flying Fortress for departure from Sioux City, Iowa, on July 25, 2022. The aircraft is one of only five active B-17s. US Air National Guard photo by Senior Master Sgt. Vincent De Groot.

“In August, off the West Coast, there’s nothing but fog for a thousand miles out there,” LeMay told Air Force Academy cadets in a 1971 speech. “And they deliberately picked this time, I’m sure.”

The Utah also reported its coordinates to LeMay late in the exercise and 60 miles from its actual location — oops. But LeMay was good at his job. With only 10 minutes remaining, he spotted the battleship between clouds. The airmen showed no mercy. From only 400 feet, the bomber ruthlessly pummeled the battleship with 50-pound water “bombs.”

“The Navy was so sure they wouldn’t be found that the men were all over the decks!” LeMay said. “Everyone was diving for the gangplanks and hatches.”

Related: Eddie Rickenbacker: America’s Most Decorated World War I Ace

American ships burn during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Dec. 7, 1941. AP photo.

Gen. Curtis ‘Iron Ass’ LeMay

During the first 11 years of his military career — until Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941 — LeMay was promoted slowly, at a peacetime pace. But after the US entered World War II, he rocketed through four ranks, rising all the way from major to major general between 1942 and 1944.

During that time, LeMay commanded the Eighth Air Force’s 305th Bomb Group, followed by its upper echelon 3rd Bombardment Division, in the European Theater. From England, LeMay led bombing raids deep into Nazi territory, often beyond the range of fighter escorts. In addition to pilot, LeMay could fill nearly every role of a 10-person air crew. Even as a high-ranking officer, LeMay would step in to navigate or drop bombs from the doors in the belly of the aircraft while training his men.

It was also in Europe that the general became widely known as “Iron Ass” or “Old Iron Pants.” Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara — who was often at odds with LeMay in the 1960s — remembered the general as steely and uncompromising, almost machine rather than man. In The Fog of War, McNamara said of LeMay, “He was the finest combat commander of any service I came across in war. But he was extraordinarily belligerent, many thought brutal. He got the report. He issued an order. He [LeMay] said, ‘I will be in the lead plane on every mission. Any plane that takes off will go over the target, or the crew will be court-martialed.’”

Related: How White Sands Missile Range Launched the Atomic Age

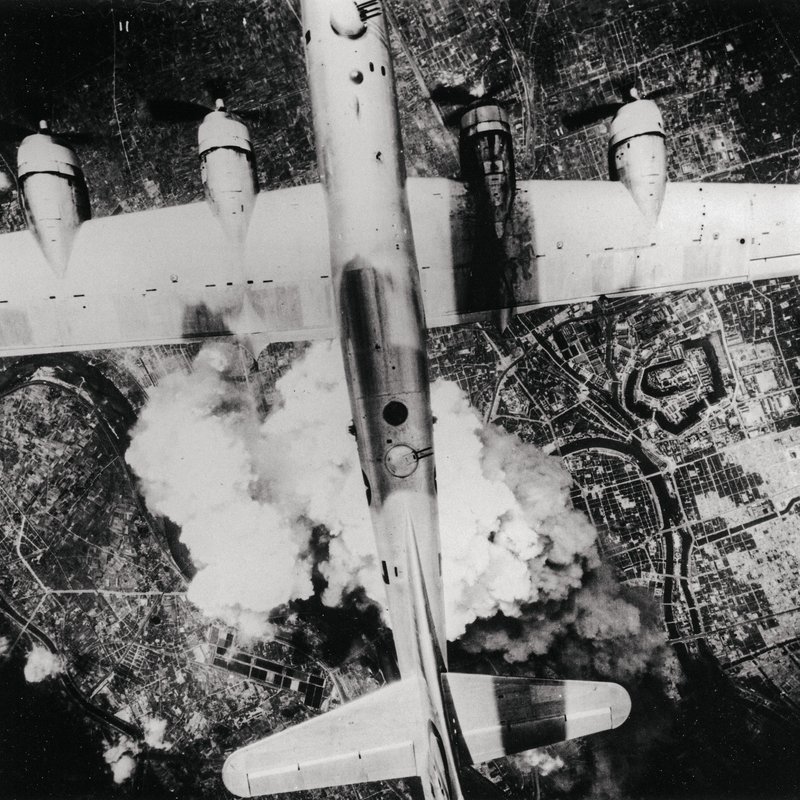

B-29s unload their incendiary bombs over Yokohama, Japan, during an air raid on May 29, 1945. The attack devastated 6.9 square miles of the port city. AP photo.

Operation Meetinghouse

On the evening of March 9, 1945, more than 300 B-29 bombers under the command of Maj. Gen. LeMay took off from the Mariana Islands to try something new. After making his bones in Europe, the battle-tested general had been tasked with rectifying America’s ineffective bombing campaign against Japan. But LeMay had implemented precise, high-altitude daylight raids in Europe that weren’t working against the island country. At high altitudes, Japan’s powerful jet stream pushed bombers too quickly past their targets. Flying in from the opposite direction, the planes were sitting ducks. LeMay had to flip the script. Just after midnight on March 10, Superfortresses from the 21st Bomber Command executed Operation Meetinghouse, firebombing Tokyo from less than 9,000 feet.

For the B-29s to deliver full payloads of incendiary munitions, each bomber was stripped of all extra weight and defenses except for tail turrets. Now, the Superfortresses could drop twice their usual payload. For the next 48 hours, roughly 2,000 tons of firebombs incinerated the “paper city’s” wood-framed buildings and killed between 80,000 and 130,000 civilians caught in the firestorm.

“We hated what we were doing,” said Jim Marich, an aviator on the mission over Tokyo. “But we thought we had to do it. We thought that raid might cause the Japanese to surrender.”

With its No. 3 engine out, this B-29 Superfortress continues its daytime bombing run over Osaka, Japan, on June 1, 1945. 21st Bomber Command photo via AP.

The flames could be seen from 100 miles away, and the carnage was unlike anything the world had ever seen. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey determined that more people likely died during the Tokyo firebombing than any other six-hour period in history.

“Can you imagine standing in front of an open bomb-bay door and smelling a city burn up?” said Ed Lawson, a B-29 gunner who flew the raid. “It was terrifying. At low altitude like that, I didn’t wear an oxygen mask. All I can say is that the smell was nauseating. I’ve never smelled anything like it since, and I don’t want to.”

From March 10 until the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in early August 1945, US firebombing campaigns decimated more than 60 Japanese cities. Years later, LeMay said, “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal. Fortunately, we were on the winning side.”

Related: Glorious Amateurs: The Legendary OSS of World War II

A B-52 Stratofortress assigned to the 2nd Bomb Wing at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, takes off from Guam on April 5, 2023. While at the head of the Strategic Air Command, Gen. Curtis LeMay kept America’s fleet of B-52s in a constant state of readiness. US Air Force photo by Airman 1st Class William Pugh.

Transforming the Strategic Air Command

On Sept. 2, 1945, when the Empire of Japan officially surrendered on the deck of the USS Missouri, LeMay was aboard the battleship, and he saw to it that hundreds of B-29s swarmed overhead. At the time, the Superfortress symbolized America’s mighty power. The B-29 had razed Japanese cities and delivered the atomic bombs that ended World War II.

After the war, LeMay went on to serve in several high-profile positions, including as the commanding general of the US Air Forces in Europe. While in that role, he organized air operations for the 1948 Berlin Airlift. Later that year, LeMay took charge of the floundering Strategic Air Command, or SAC. The unit was supposed to be America’s nuclear gut-punch to the Soviet Union. But when LeMay took command, the atomic strike force had fewer than 100 nuclear-capable bombers, which couldn’t realistically deter Russia. Over the next decade, LeMay transformed the SAC into a well-oiled, all-jet global strike force made up of more than 2,000 nuclear-capable aircraft.

Related: What Really Happened at Vietnam’s Hamburger Hill?

LeMay’s Later Years

While at the Strategic Air Command, LeMay, then 44, was promoted to four-star general, which made him the youngest service member to earn the rank since Ulysses S. Grant. By the end of his career, he would serve as a four-star general for longer than any other airman in US history. But first, LeMay would fill the highest position in his branch, serving as the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force from 1961 through 1965.

President John F. Kennedy, back to camera, in the White House on Oct. 30, 1962, with four Air Force officers, including Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Curtis LeMay, right, who consulted with the commander-in-chief during the Cuban Missile Crisis. AP photo.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, LeMay was amongst the military advisors who consulted with President John F. Kennedy while under DEFCON 2 — the highest level of alertness before nuclear war. In a secretly recorded meeting on Oct. 19, 1962, LeMay said, “I just don’t see any other solution except for direct military intervention.” But Kennedy did.

Because of LeMay’s proclivity for overwhelming force, the war hawk often bickered with his superiors, including President Kennedy and then Lyndon B. Johnson. He was always a hammer searching for a nail to bomb into oblivion. About the North Vietnamese, LeMay wrote in his book, “My solution to the problem would be to tell them frankly that they’ve got to draw in their horns and stop their aggression or we’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Ages.”

Gen. Curtis LeMay pilots his last flight as an Air Force officer, flying a C-135 out of Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, in February 1965. US Air Force photo.

After leaving his post as Chief of Staff of the Air Force in 1965, LeMay moved to California. In 1968, the general joined the presidential election as former Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s running mate on a third-party ticket. Both men were controversial figures. Wallace was an infamous segregationist, and LeMay had made a name for himself as a tactless, trigger-happy military commander.

After the pair’s ticket gained only 13% of the vote, LeMay largely receded from public life. Roughly two decades later, he died at 83 from a heart attack on Oct. 1, 1990, at March Air Force Base, California. LeMay was buried at the Air Force Academy Cemetery in Colorado Springs.

Read Next: SR-71 Blackbird: The Spy Plane That Could Outrun Missiles

Jenna Biter is a staff writer at Coffee or Die Magazine. She has a master’s degree in national security and is a Russian language student. When she’s not writing, Jenna can be found reading classics, running, or learning new things, like the constellations in the night sky. Her husband is on active duty in the US military. Know a good story about national security or the military? Email Jenna.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.