Marlene Dietrich served in the Morale Branch of the OSS. Photo courtesy of the International Spy Museum.

On March 5, 1944, Flight Officer Chuck Yeager bailed out of his P-51 Mustang and pulled the ripcord of his parachute at 8,000 feet. His aircraft plummeted to the ground and exploded on impact. Yeager landed safely in a forest clearing somewhere in Nazi-occupied France.

Almost immediately, half a dozen French resistance fighters were at Yeager’s location. They stashed his parachute, then whisked him to a nearby safe house. Yeager’s bomber jacket was exchanged for civilian clothes, and he was given enough food to fill his stomach.

Over the next two weeks, the pilot and his rescuers moved clandestinely through the French countryside, evading the Gestapo as they jumped from safe house to safe house en route to the Pyrenees mountains. The Pyrenees provided one of the most reliable escape routes out of France during World War II. Accompanied by local guides, Yeager and three other American aviators trekked through the snowy mountains for four days before finally arriving in neutral Spain.

The men and women who assisted Yeager in his escape were not just random strangers. They belonged to a highly organized network of resistance groups who worked in close cooperation with Allied intelligence to rescue GIs stranded in enemy territory. Over the course of World War II, the network helped approximately 1,000 downed airmen and escaped prisoners of war sneak across France’s treacherous southern border and reach friendly lines through Spain.

Related: Inside The OSS’s League of Lonely War Women

The Limping Lady

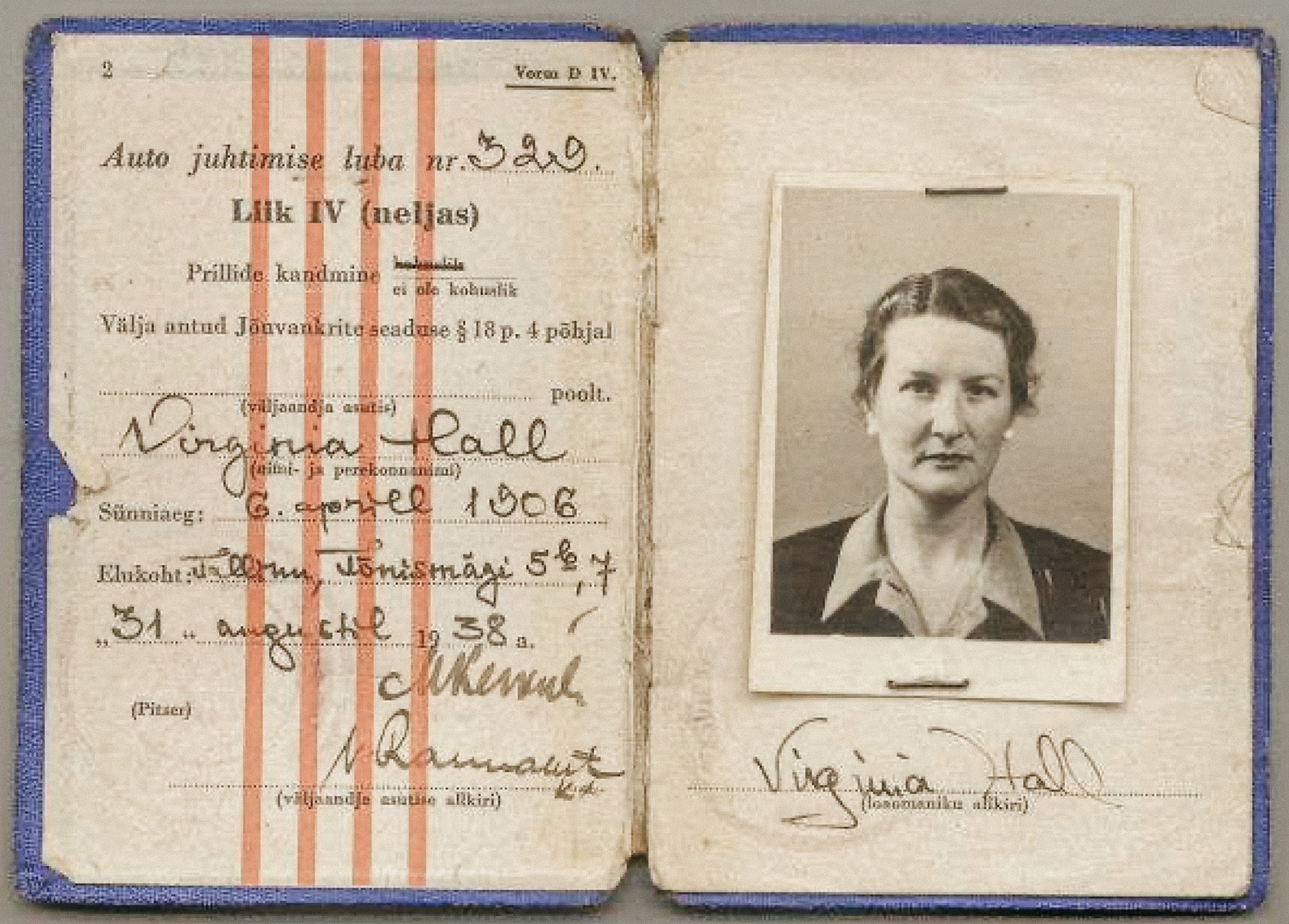

Virginia Hall was a legendary intelligence officer having worked with the British SOE and American OSS during World War II. She later served with the CIA after it was established in 1947. Photo courtesy of the CIA.

Among the most famous individuals involved in the rescue efforts was Virginia Hall, a one-legged foreign service officer from Baltimore, Maryland. Prior to becoming a secret agent, Hall had worked as an ambulance driver for the army of France and was in the country when it fell to the Germans. In 1941, while living in neighboring Spain, she was recruited by the Special Operations Executive — the British counterpart to the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS — to help the agency forge a working partnership with the nascent French resistance movement.

Hall returned to France disguised as a reporter for the New York Post. Basing herself in the city of Lyon, she and her team got to work organizing the various partisan groups in the country into a unified rebel force. The job also entailed establishing safe houses to shelter other secret agents, as well as Allied airmen and fugitive POWs trying to evade the Gestapo. Hall’s work did so much to bolster the resistance that the Gestapo added her to their most-wanted list, labeling her “The Limping Lady,” as they didn’t know her actual name.

In 1942, the Germans seized control of the city of Vichy, one of Hall’s main areas of operations. At risk of capture, she used the same escape route established by her team to flee the country over the Pyrenees, all while lugging her prosthetic leg, which she called “Cuthbert,” through ice and snow. Hall eventually returned once more to occupied France, except this time as a member of the OSS, the forerunner to the CIA.

Related: The Daring Exploits of Virginia Hall, World War II’s Most Notorious Spy

The OSS Director Was a Medal of Honor Recipient

"Wild Bill" Donovan was one of the most decorated soldiers of World War I. He was awarded the Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross, and the Medal of Honor. Photo courtesy of the CIA.

The security failures that allowed Japan to carry out its devastating attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 led President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to establish America’s first spy agency devoted to the work of collecting intelligence abroad.

Roosevelt tasked an aging yet battle-hardened US Army officer named William J. Donovan with drafting the blueprint for the new agency. Known as “Wild Bill,” Donovan had served in World War I as the commanding officer of the US Army’s 165th Infantry Regiment. Donovan’s commendations included the Medal of Honor, which he earned in October 1918 while fighting near the French town of Landres-et-St. Georges. According to his award citation, then-Lt. Col. Donovan led his men in a successful assault on a heavily defended German position. He was shot in the leg but refused evacuation.

Donovan returned to the States a bona fide war hero. He became a successful lawyer in New York and even ran for governor. Though his campaign failed, it gained him the political connections that would ultimately put him on Roosevelt’s radar.

"Wild Bill" Donovan, second from left, in Burma, where he risked his life by going behind enemy lines. Photo courtesy of the OSS Society.

The president’s first task for Donovan was to embark on a world tour to meet with foreign leaders and intelligence officials in order to forge strategic partnerships for conducting covert operations in the Mediterranean. His journey took him to several European and North African countries. In England, he met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as well as the heads of Britain’s Ministry of Economic Warfare, Political Warfare Executive, and the heads of the SOE.

After Donovan returned to Washington, Roosevelt named him Coordinator of Information, the head of the nation’s first peacetime intelligence agency. A year later, in June 1942, the agency was reorganized into the OSS, with Donovan still at the helm.

Donovan was promoted to the rank of major general when he assumed command of the OSS. He organized the agency into two main divisions: Intelligence Services and Strategic Services Operations.

Intelligence Services units included Secret Intelligence, X-2 (counterintelligence), Research & Analysis, Foreign Nationalities (domestic-based intelligence collected from foreign national groups for psychological operations abroad), and Censorship & Documents. Strategic Services Operations was composed of Special Operations, Morale Operations, Maritime Unit, Special Projects, Field Experimental Unit, and Operational Groups.

Related: How Irish American Spymaster ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan Earned His Nickname

Oh So Social vs. The Glorious Amateurs

Chinese paratrooper trainees and their OG instructors prior to their first mass tactical jump, China 1945. US Army photo.

Early on, the OSS earned a not-so-flattering nickname because of its reputation as an agency made up of aristocrats and Ivy Leaguers. As Washington’s old guard saw it, OSS officers were more interested in attending “Oh So Social” cocktail parties than performing tradecraft in the field.

In time, the OSS overcame that reputation as Donovon filled its ranks with highly educated men and women who were also willing to get their hands dirty. The ideal OSS officer, according to Donovan, was a “Ph.D. who could win a bar fight.” He liked to refer to the members of his unit as “glorious amateurs” because many of them lacked prior military experience but ultimately proved to be highly capable spies.

The so-called glorious amateurs came from all walks of life, such as singer Marlene Dietrich, who was already internationally famous when she volunteered for service with the OSS. Dietrich was assigned to the OSS’s Morale Branch, which was responsible for disseminating anti-Axis propaganda across Europe and the Far East. Her primary job was writing and recording music intended to cause friction among enemy troops.

Sterling Hayden, right, served in the Maritime Unit with the OSS. Photo courtesy of the OSS Society.

Since her involvement with the OSS was a secret, her music was broadcasted uncensored around the world. Her most famous piece of propaganda, the hit song “Lili Marlene,” became so popular in Germany that the Nazi government eventually caught on and banned it from being played on the radio.

Another notable member of the OSS was actor Sterling Hayden, who went on to achieve Hollywood stardom after the war. Hayden served in the OSS Maritime Unit — a predecessor to today’s Navy SEALs — and earned the Silver Star crossing the Adriatic Sea from southern Italy to supply Yugoslavian communist rebels with weapons.

There was also future celebrity chef Julia Child, who served as a research assistant in the OSS Secret Intelligence division. During the war, she worked stateside helping develop a shark repellent that her superiors hoped would deter the amphibious predators from tampering with underwater explosives and attacking sailors and airmen stranded at sea.

Related: Julia Child: The OSS Officer Who Introduced French Cuisine to American Households

Operational Groups and the Jedburghs

Members of the OSS Italian Operational Group. Photo courtesy of the OSS Society.

In 1943, the 400-acre Congressional Country Club in Bethesda, Maryland, was leased to the US government and transformed into a training ground for commandos. The driving range became a firing range, the sand traps were used for grenade practice, and the fairways on the 17th and 18th holes became simulated minefields. Over the next two years, more than 2,500 OSS recruits underwent training at the CCC, acquiring skills in espionage, demolitions, sabotage, and weapons handling.

Most of the officers trained at CCC were subsequently assigned to OSS Operational Groups, which conducted paramilitary operations in France, Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Burma, Malaya, and China. The OGs worked behind enemy lines alongside local partisan forces to sabotage key Axis infrastructure, such as railroads and bridges.

The most specialized OSS commandos were a small faction of airborne paramilitaries called the Jedburghs, whose primary AO was Europe. The Jedburgh teams typically contained one American, one British, and one French commando. Belgians, Dutchmen, and Canadians occasionally worked with the teams too.

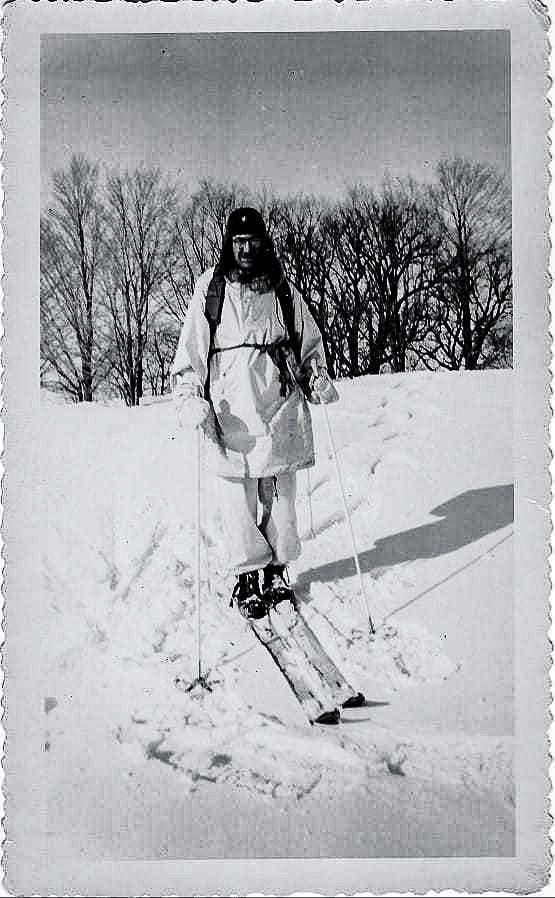

William Colby, a future director of the CIA, participated in a daring ski-parachute mission in Norway during World War II. He is pictured here on skis. Photo courtesy of the CIA.

The first Jedburgh team ever deployed parachuted into France the night before D-Day. Their objective was to assist the invasion force by leading pockets of resistance forces against German units based inland. As the march to Berlin got underway, approximately 90 more Jedburgh teams were dispatched to Europe. They primarily operated in German-occupied France and worked closely with various French resistance guerrilla groups, including the Maquis, who smuggled Yeager out of France after he was shot down.

At least two Jedburgh officers leveraged their training and wartime experiences to further improve America’s military and intelligence capabilities after the war. Aaron Bank, who commanded Jedburgh Team Packard for six weeks in France’s Rhone Valley, went on to help establish the Green Berets. (He has been called the “Father of Special Forces.”)

The other was William Colby, who during the war led a daring ski-parachute mission in Norway that succeeded in severing a key Nazi railroad. After the OSS was disbanded in 1945, Colby joined the CIA and later became its director.

Related: The Legend of Jack Hemingway: OSS Commando, Fly Fisherman, POW, Writer

OSS to CIA

On the south wall of the original headquarters building lobby is the OSS Memorial. The memorial is dedicated to the men and women who lost their lives while serving in the OSS during World War II. The memorial consists of a single star on the wall and a book that lists the names of the 116 OSS fallen. Photo courtesy of the CIA.

By the war’s end, more than half of the OSS’s 13,000 officers had served tours overseas. Donovan tried to persuade President Harry S. Truman to let him reorganize the unit into a peacetime intelligence agency, but to no avail.

Instead, Truman decided to disband the OSS and mandated the establishment of the Central Intelligence Group to take its place. But even though the OSS was gone, its legacy would survive in many ways. Secretary of War John J. McCloy, a personal friend of Donovan’s, absorbed OSS Secret Intelligence and X-2 into the War Department’s Strategic Services Unit. And when the National Security Act of 1947 turned CIG into the CIA, many OSS veterans, including Hall and Colby, joined the service and helped lay the groundwork for the agency as it stands today.

Nor have the extraordinary accomplishments of Donovan and his glorious amateurs been forgotten. In 2016, the OSS received the Congressional Gold Medal for “implementing a system of strategic intelligence during World War II and providing the basis for the modern-day American intelligence and special operations communities.”

Read Next: OSS Guide Maria Gulovich Escaped the Nazis and Earned the Bronze Star

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.