Peace in the Clouds: How One of the World’s Deadliest Warriors Found His Zen

Retired Air Force special operator and author Dan Schilling spends most of his time enjoying the quiet of Utah's natural beauty.

The sun has barely crested the snowcapped peaks of “his canyon” when Dan Schilling pulls into the back lot of Snowbird ski resort. He grabs his ruck — packed with snowshoes and hiking poles — from the back seat and shuts the truck door.

His white pickup matches his long hair and beard, camouflaging him against the snowy, late-spring Utah landscape. At nearly 60, Schilling’s white hair shows his age, but his high energy suggests he’s anything but old.

“You’re gonna love it, man. These views never get old,” he says, cinching his pack-straps tight and turning with a smile. “Ready?”

With that, we step off to climb 11,000 feet through snowbanks and loose granite, because that’s how the soft-spoken author likes to relax.

Schilling’s 30 years in special operations are evident in the ease with which he ascends the steep path. After spending half of his life operating in some of the most austere environments in the world, he’s comfortable being uncomfortable. Schilling served as an Air Force special tactics officer and, before that, a combat controller — in other words, as one of the deadliest warriors in the world. Now, when he isn’t challenging himself or stirring up adrenaline in the great outdoors, Schilling devotes his unending energy to writing books.

In a climb toward his goal of becoming a New York Times bestselling author, he’s published three books since 2004, including Alone at Dawn: Medal of Honor Recipient John Chapman and the Untold Story of the World’s Deadliest Special Operations Force. After initially balking at the idea of writing that book, preferring to focus on writing fiction, Schilling accepted the responsibility of telling the story of the Air Force combat controller who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in Afghanistan in 2002.

Five years after retiring from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel, Schilling hasn’t slowed down. He spends nearly every day either hiking, skiing, or speed riding — his favorite. That’s when skis aren’t enough of a thrill, so you strap on a parachute and combine the two extreme sports into a single, adrenaline-pumping method of descending mountains.

“I flew down that little bowl yesterday. Beautiful,” he says, pointing to a wide basin across the draw from us with one set of ski tracks still visible in the snow. “There’s not as much snow as there should be this time of year, but this weather is still perfect.” Schilling unofficially adopted Little Cottonwood Canyon as his own when he moved to nearby Draper. He’s meticulous about its preservation, picking up the tiniest pieces of trash he finds along the route to the summit.

“Snowbird’s done a really amazing job with preserving the integrity of the canyon here,” he says. “I mean really great.”

He’s personally invested in the small patch of the Wasatch Mountains he now calls home. It’s here that Schilling does most of his writing.

Schilling’s writing career kicked off in 2004 with The Battle of Mogadishu, a collection of firsthand accounts of the daylong firefight. The book’s final chapter — “On Friendships and Firefights” — is Schilling’s own recollection of the battle. He was one of just four combat controllers involved in Operation Gothic Serpent.

Operating on the ground, the lesser-known Air Force members direct fire-control from myriad aircraft. They can infiltrate some of the most non-permissive environments and deliver devastating firepower. On top of being lethal versions of air traffic controllers, they’re all scuba, airborne, and HALO certified, making them some of the most versatile and deadly operators in America’s arsenal.

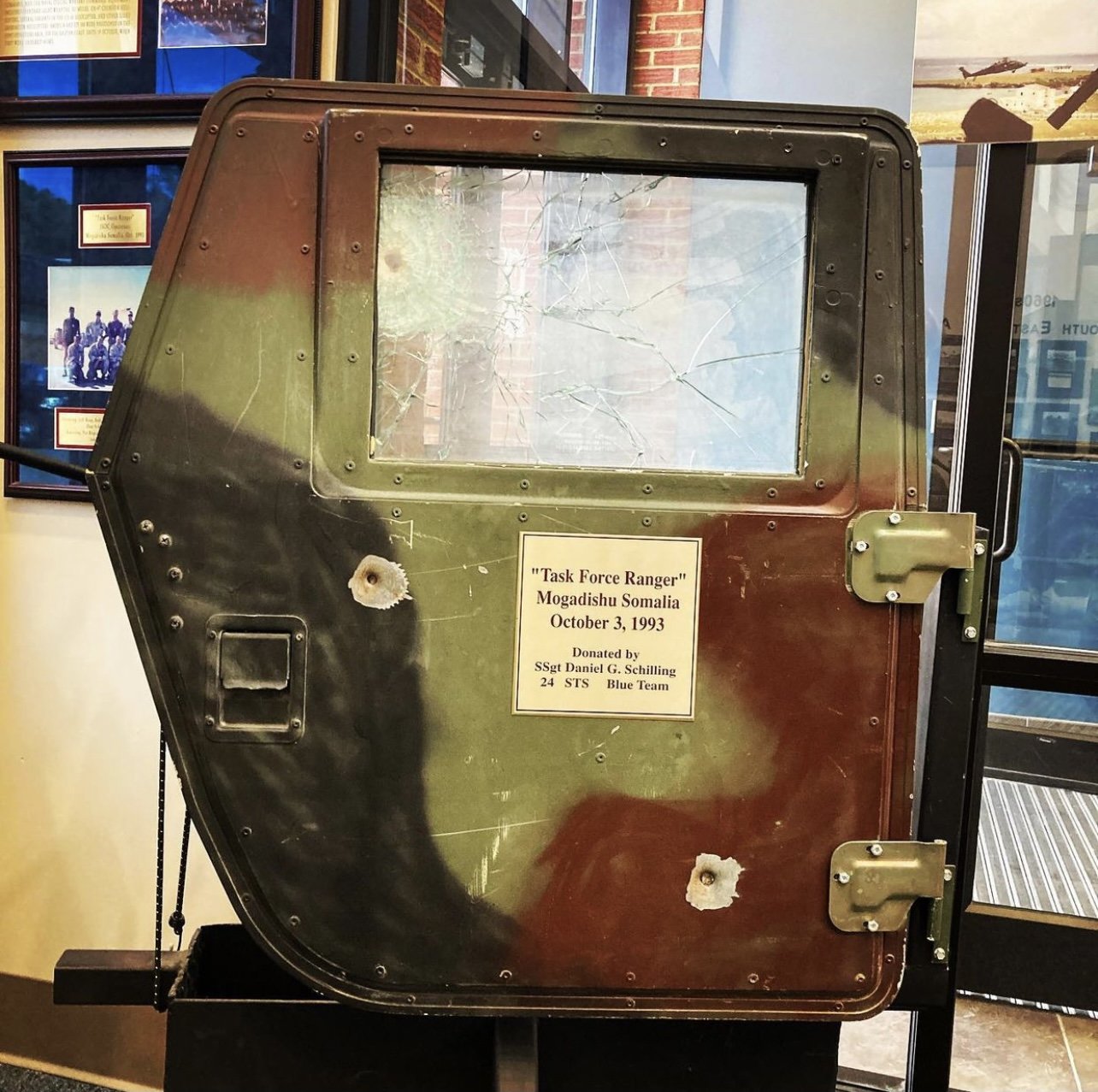

On that fateful October morning in 1993, Schilling found himself in the rescue vehicle convoy, where he was exposed to some of the battle’s heaviest fighting. As the convoy of Humvees and trucks attempted to make their way to the downed Black Hawks, casualties mounted and ammunition ran low until the group was eventually forced to return to base. Schilling narrowly escaped death several times before the fight was over. The armored door he installed before the mission stopped several bullets intended for him.

In “On Friends and Firefights,” Schilling recalls feeling too tired during the battle to empathize with a Somali man he saw cradling his dead granddaughter. Now, nearly three decades after Mogadishu, what he recalls most is the love that permeated those who fought there.

“The things I did were for the people I love — the guys I was with, who I was willing to sacrifice my life for.”

And while he doesn’t express guilt for killing people during his long career, it left a permanent mark on his psyche. Now, he tries to help people whenever he can.

About 9,000 feet up Hidden Peak, Schilling pauses and looks over his shoulder. Noticing how the gap between us has grown, he says, “How about we pause here for a second? I could use some water.” We sit for a moment and take in the sheer magnitude of the mountains. We both know words won’t do them justice, so we sip water in silence.

Schilling is comfortable in silence. He spends hours alone on the mountain every week. He’s a Buddhist, and while he doesn’t put a label on it, the time he spends on the high peaks is his meditation.

His journey to Buddhism — which he is quick to point out is a philosophy, not a religion — began with a book: The Power of Now. Its focus is on living in the present moment, something Schilling takes to heart and practices every day. When I tell him that book is sitting on my shelf, but I haven’t pulled it to read yet, his gaze becomes intense.

“It will be helpful,” he says. “You’re the right kind of person — you’re ready for that book.”

He explains how Buddhism is about finding peace, but you have to make the journey yourself. “You can take nobody’s word for it,” he says. As I continue to take notes about his latest work and philosophy, he seems to be studying me.

In 2006, when Schilling saw the need for greater support for Gold Star families, he set out to raise money for the Special Operations Warrior Foundation. He BASE jumped a record-breaking 201 times in a single day. He completed most of the jumps after an especially hard landing early in the day broke his arm. After the injury, he brought his team of chute-packers together for a talk.

“I didn’t want them rushing through the process of preparing the parachutes,” he says. “In BASE jumping, there’s no extra time to let your canopy open up, and there’s no reserve chute. I couldn’t afford to die during the fundraiser because then all the publicity would just be about tragedy.”

Matt Eversmann is an Army Ranger who fought alongside Schilling in Mogadishu.

“Dan has always been more concerned about others than himself,” Eversmann told me. “He’s just that kind of guy.”

Schilling credits Buddhism with this worry-free outlook, but years of facing death in combat operations likely played a role as well.

“I’m going to die, and I don’t mind dying. I want to live peacefully with the people I love, but I am going to die,” Schilling says matter-of-factly.

Death is a topic with which Schilling is intimately familiar, and it often plays heavily in his books. Alone at Dawn is the story of John Chapman’s death and, ultimately, how the Medal of Honor immortalized him.

Chapman was part of a small team of Americans who became engaged in an intense firefight with al Qaeda atop Takur Ghar mountain in Afghanistan. The Americans were attempting to recover a wounded Navy SEAL when they began taking fire from multiple directions. ISR recordings captured Chapman’s heroic actions as he led an assault uphill through thigh-deep snow. When Chapman was eventually shot and incapacitated, the SEALs withdrew from the mountaintop, leaving him alive and alone.

Despite mortal wounds, Chapman regained consciousness and continued to kill enemy fighters. As a quick-reaction force approached the mountain, Chapman decided to leave the relative safety of a bunker and assault the remaining enemy positions to draw fire away from the helicopter.

The QRF helicopter was struck by an RPG and forced to land downslope from Chapman. As the team disembarked from the stricken helicopter, three Americans were immediately killed. While the rest of the QRF fought their way out of the kill zone, Chapman continued to press the attack in an attempt to draw the enemy’s fire. After suffering 16 bullet and shrapnel wounds, Chapman was finally shot in the heart and killed.

“It’s a love story,” Schilling says of Alone at Dawn. “A love story between John and his wife, between John and the guys that left him for dead, and John and the guys who he didn’t know that he sacrificed himself for. That’s an act of love.”

Schilling wrote the book with two primary objectives: to preserve the story of Chapman’s sacrifice and to show the world the essence of combat control.

“Combat controllers are the deadliest individuals to walk a battlefield in the history of human warfare. Period. There’s no caveat to that,” he says, standing up to continue our trek skyward. “They kill more people than anybody else.”

As we climbed long enough to experience the weird sensation of getting sunburned from snow, Schilling points out that combat controllers rarely receive recognition. In 2003, Delta Force killed Saddam Hussein’s sons, Uday and Qusay. But a combat controller was actually responsible for the lethal ordnance that dispatched them. In 2009, during the Maersk Alabama hostage situation — later dramatized in the movie Captain Phillips — one of the snipers aboard the USS Bainbridge’s fantail who killed Somali pirates was a combat controller. And Schilling points out that the airmen were also left out of the blockbuster film Black Hawk Down. Did he feel slighted by the omission?

“Combat controllers got cut because no one gives a shit about Air Force guys!” he half-jokingly responds. He’s quick to add that it’s just a movie, and he doesn’t take it personally.

Thanks to Schilling’s work in Alone at Dawn, combat controllers will soon have their own film. The book is being adapted as Combat Control, with Jake Gyllenhaal cast to portray Chapman. Schilling says he’s pleased with the people behind the project and confident they will make an A-list movie. But in addition to his demand that they remain faithful to the integrity of who Chapman was and the essence of combat control, he hopes the film has an effect similar to a particular B-movie from the 1990s.

Schilling explains how Navy SEALs had a powerful impact on the Navy. “Along came this crappy little movie starring Charlie Sheen that branded them to the country. Suddenly, it became, ‘There’s the Navy, and then there’s SEALs,’” he says mockingly. Schilling says, after working alongside SEALs throughout his career, he has nothing but respect for them, but the Air Force never had a similarly defining piece of pop culture. He hopes that Combat Control gives the branch’s special operations some overdue recognition.

We make our way higher and higher up Schilling’s canyon while he shares a never-ending stream of mountain trivia.

“See that little shed across the way?” he asks, pointing to a tiny wooden structure on the mountainside opposite from us. “That’s got a 105 mm howitzer in it.”

He explains how the canyon was the first place in the world to use military cannons for avalanche control, a practice that’s now common across the globe. He tells me how, in his spare time, he’s helping build a tunnel museum — a project for which he put his clandestine skills to work, acquiring a recoilless rifle from a shady white supremacist group in Montana. He brushes over the details and jokes that it hadn’t been a safe place to share his political beliefs. He went in, stayed just long enough to get the artifact, then got out.

He points to the unremarkable entrance of an abandoned tunnel and says, “That mine over there almost started a war with England.”

In the 1800s, the Emma Silver Mine produced $3.8 million in silver and created a boomtown of more than 8,000 people. A series of avalanches later wiped out the entire town, but not before a shifty American businessman sold the depleted mine to the British with the false promise that it housed more silver.

It’s been a few hours since we stepped off from the car, and the top of the mountain is within reach. It’s been just long enough for my feet to let me know blisters are on the way. Schilling is on the top of this mountain — or one of its neighbors — nearly every day. They’re part of his routine. Most people drink a cup of morning coffee; Schilling hikes a mountain. He doesn’t drink coffee or alcohol or eat meat anymore. I’d ridicule him for it if he weren’t kicking my ass up the mountain at nearly twice my age.

“I’m not an asshole, though,” he adds. “If someone cooks meat, I’ll still eat it.”

We decide the best place to sit down and have a conversation is at the day lodge on top of Hidden Peak. There’s a gondola lift that runs to the top and a small snack bar with a scenic overlook for mountain lovers who prefer getting a blister-free view. My knees are grateful for not having to make the descent by foot. Once we make the final few hundred yards to the top, we grab some water and a seat that overlooks the surrounding vista. The few clouds that remain seem to be beside us, not above.

Now that our lungs don’t have to work so hard, Schilling begins to open up about his unique past. I ask him about a sentence that stood out to me in his newest book, The Power of Awareness: “Killing people, in particular, even when justified, is a net negative life experience.”

“I rarely speak in absolute terms, but in absolute terms, I believe that’s true,” he says with a bit of sadness. “The reason why is, it does nothing to advance you as a human. Contrarily, it diminishes you. At least, it diminished me. I’ve killed more than some people; I’ve killed far fewer than many of my friends. But it’s not about numbers. All it takes is one.”

As we bond over the shared knowledge, I begin to say, “The idea of killing someone is wholly different when you have some more years under your belt and a little maturity. As a young man in combat, killing—”

“It’s easy,” he says, finishing the sentence.

We agree it’s probably too easy for young men to kill in combat. Taking a life used to bother Schilling, but after years of reflection, Buddhism has helped him come to terms with the fact that he can’t change the past. Instead, he focuses on helping people in the present.

His desire to help is what drove him to write The Power of Awareness: And Other Secrets From the World’s Foremost Spies, Detectives and Special Operators on How to Stay Safe and Save Your Life. During his long career, Schilling recognized the importance of trusting his instincts. He says he felt a duty to share what he learned with others, and he wants people to use his book as a guide to help sharpen observation skills, which he argues are more valuable for self-defense than a firearm.

The Power of Awareness is part reference guide, part instruction manual, and part entertainment. Schilling’s gift as a storyteller shines through in each of the book’s vignettes, making it a fun read.

When we finish chatting about his book, we take the gondola back down the mountain. The ride is peaceful, but after too many quiet minutes, Schilling can’t help but tell me how friends of his — but definitely not him — used to sneak on top of the gondola cars and BASE jump off of them. Now that he’s older, he swears he’s toned down his taste for extreme activities. After all, he’s married to the love of his life and can’t stomach the idea of her having to live without him because he died doing something avoidable.

“He’s kind of like this ball of incredible energy and intelligence,” his wife, Julie, tells me. “It’s like he’s not even of this earthly plane, but he’s this extraordinary being. As long as he can climb up the mountains to speed-fly, he will. He needs to fly.”

Schilling says, with Julie in his life, the risk no longer seems quite worth the reward, but I doubt he’ll ever stop altogether.

After just one morning together, I’ve come to admire Dan Schilling greatly. Not because he’s a veteran of the famous Black Hawk Down battle, and not because he’s one of the most accomplished special operations veterans I’ve ever met, but because, despite all of the experiences he’s lived that would make for an easy excuse to be a bitter man, he’s perpetually positive.

Schilling has spent nearly half of his life trying to be more than just “Black Hawk Down Dan.” That was one of the first things he said when we met, and I spent the rest of the day mulling over bad replacements: Buddhist Dan, Benevolent Dan, Badass Dan. The list gets worse.

As we shook hands and prepared to part ways, I realized the reason I grew so fond of him in such a short time was that no single moniker could capture who he was. He’s equally as complex as he is generous, and his desire to grow as a person and help others is infectious.

Read Next: The Legend of Jim Capers: The Hero Who Never Was

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.