Almost 40 Years Before ‘Saving Private Ryan,’ a Magazine Story Examined the Horrors of D-Day

Troops in an LCVP landing craft approaching Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The most famous telling of the D-Day invasion is the second scene of Saving Private Ryan. When it landed in theaters in 1998, the gore- and death-filled, 20-minute sequence delivered a raw emotional punch of terror to audiences, presenting the story of Omaha Beach on the morning of June 6, 1944, as a horror movie. Audiences watched as young soldiers were killed and maimed, seemingly at random. The sequence was so violent and terrifying that it was hailed as a “turning point” in how Americans viewed the Normandy landings, a view that put the terror and suffering of soldiers in combat ahead of the heroism and ultimate victory of World War II’s closing act.

But what Saving Private Ryan did for movie audiences in the late ’90s, “First Wave at Omaha Beach” did for readers in 1960, when most WWII veterans were entering middle age, and when a generation of baby boomers was just beginning to understand its parents’ war. Published in the November 1960 issue of The Atlantic, “First Wave” was written by S.L.A. Marshall, a World War I veteran and controversial military historian. He had grown angry as war movies and official Army histories of the 1950s emphasized relatively bloodless, comic-book-style war experiences.

“Unlike what happens to other great battles, the passing of the years and the retelling of the story have softened the horror of Omaha Beach on D Day,” Marshall’s article begins.

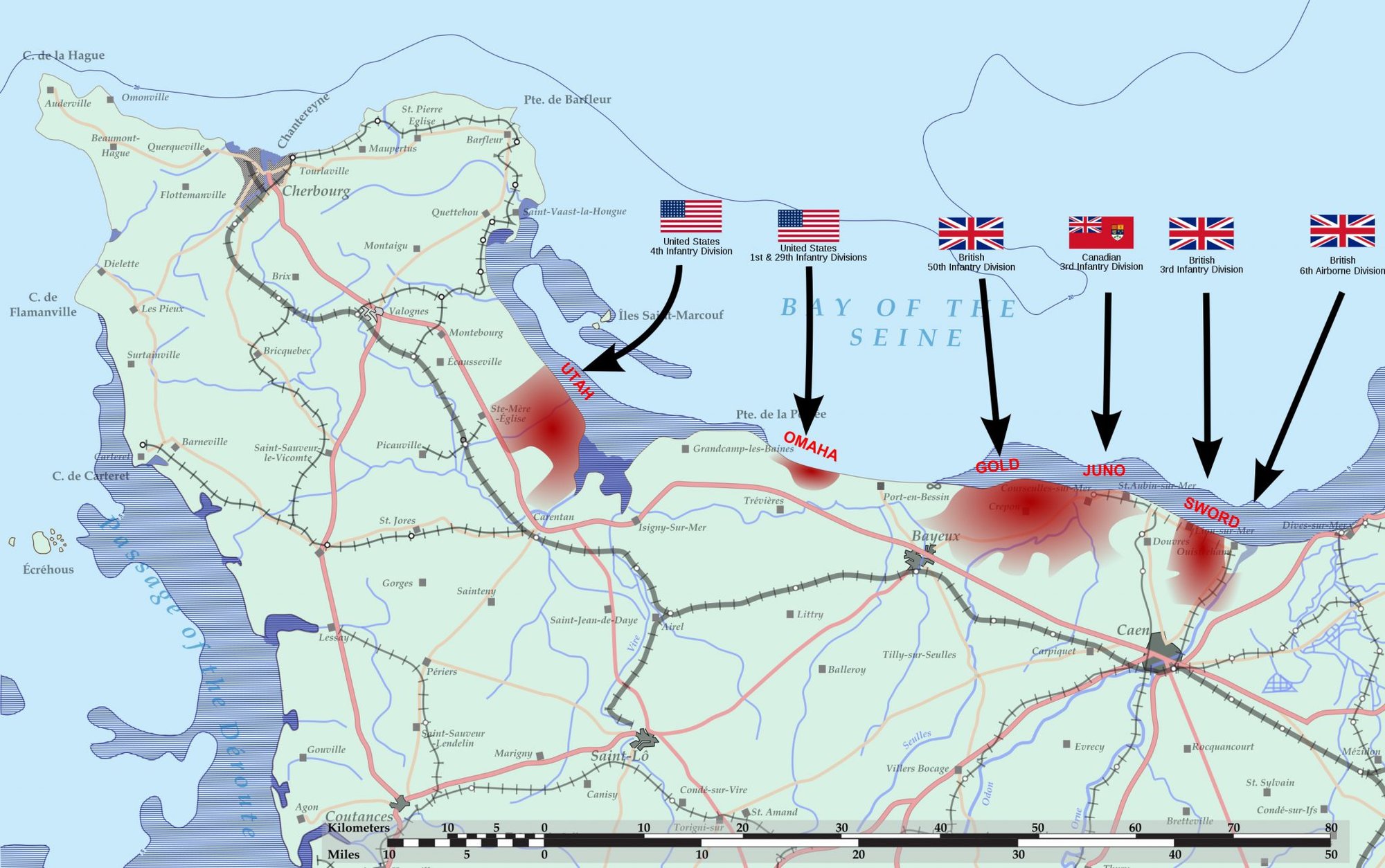

Over the next 5,000 words, Marshall used personal details from his Normandy notebook covering the landing of every Omaha company, and he followed the landings through the lens of two companies that — unlike the Rangers that Tom Hanks portrayed in Private Ryan — were shredded almost to the last man on D-Day: Able Company and Baker Company of the 116th Infantry, 29th Division.

Able Company was the first to approach Omaha Beach. Baker Company, led by Lt. Walter Taylor, was scheduled to insert 26 minutes later.

Like Saving Private Ryan, Marshall opened his story inside the seven landing craft — or Higgins boats — carrying Able Company toward the shore. At 1,000 yards from the beach, an artillery shell landed inside Boat No. 5. Six men drowned before help arrived, and 21 others helplessly paddled in the waves. All six remaining boats reached within 100 yards of the beach before another shell connected with Boat No. 3, killing two men immediately and leaving another dozen to drown under the weight of gear. At 6:36 a.m., the ramps were dropped, and German MG-42 machine-gun teams were signaled to initiate their gunfire from both ends of the beach.

“Able Company has planned to wade ashore in three files from each boat, center file going first, then flank files peeling off to right and left,” Marshall wrote. “The first men out try to do it but are ripped apart before they can make five yards. Even the lightly wounded die by drowning, doomed by the waterlogging of their overloaded packs. From Boat No. 1, all hands jump off in water over their heads. Most of them are carried down. Ten or so survivors get around the boat and clutch at its sides in an attempt to stay afloat. The same thing happens to the section in Boat No. 4. Half of its people are lost to the fire or tide before anyone gets ashore. All order has vanished from Able Company before it has fired a shot.”

Seven minutes after the ramps of the Higgins boats were released, Able Company was leaderless. Within 10 minutes, every sergeant was either dead or wounded. After 30 minutes, approximately two-thirds of Able Company are shot dead or drowned. Of seven-boat company, only a handful of men were even able to fight, though they were leaderless and had no plan on how to do so. Six survivors stranded on the extreme right flank broke free. Four collapsed on a cliff shelf and lay there the rest of the day, while two others joined Second Ranger Battalion and their assault on Pointe-du-Hoc.

As the six Higgins boats carrying Baker Company came closer to the shore, their passengers realized how completely the Germans had devastated Able company. Capt. Ettore V. Zappacosta pulled a Colt .45 pistol in the command boat and demanded the coxswain land on Able’s position. Three artillery shells just missed their boat, and 75 yards from shore, Zappacosta ordered the ramps released.

“Zappacosta jumps first from the boat, reels ten yards through the elbow-high tide, and yells back: ‘I’m hit,’” Marshall wrote. “He staggers on a few more steps. The aid man, Thomas Kenser, sees him bleeding from hip and shoulder. Kenser yells: ‘Try to make it in; I’m coming.’ But the captain falls face forward into the wave, and the weight of his equipment and soaked pack pin him to the bottom. Kenser jumps toward him and is shot dead while in the air. Lieutenant Tom Dallas of Charley Company, who has come along to make a reconnaissance, is the third man. He makes it to the edge of the sand. There a machine-gun burst blows his head apart before he can flatten.”

Marshall then describes the rest of Able and Baker’s fates: One Baker Company boat attempted to follow the first and sank, killing all 31 men on board. The four remaining landing crafts veered right and left in desperation. Two of the four jettisoned their soldiers into direct fire or deadly “drowning water,” as Marshall called it. Most of them were drowned or torn apart, with a handful of survivors moving aimlessly from one spot of cover to the next, many of the men spending America’s most famous morning of battle not firing a single shot. A third boat team successfully joined the Rangers at Pointe-du-Hoc.

A rare bright spot was Lt. Walter Taylor’s boat, which landed at a section of the beach next to the village Hamel-au-Prêtre. Taylor and most of his boat team scrambled onto the beach without being targeted. Taylor led his team crawling across the sand and over a seawall. A German machine-gun team killed four and wounded two more of the team during its move.

To his right, Taylor saw lieutenants Harold Donaldson and Emil Winkler shot dead, but he led his men straight up the bluff into Vierville. In a two-hour firefight, Taylor and his team wiped out a German platoon. They regrouped in the village, and Taylor assumed the role of the company commander in charge of 28 surviving Baker Company soldiers.

By the end of the day, Taylor and his men had fought nearly half a mile ahead of any other members of the United States Army, though his boat team had lost almost half its numbers — one of Able and Baker’s best survival rates.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.