The Surgeon Who Saved the Last 9/11 Survivor Now Trains Green Beret Medics

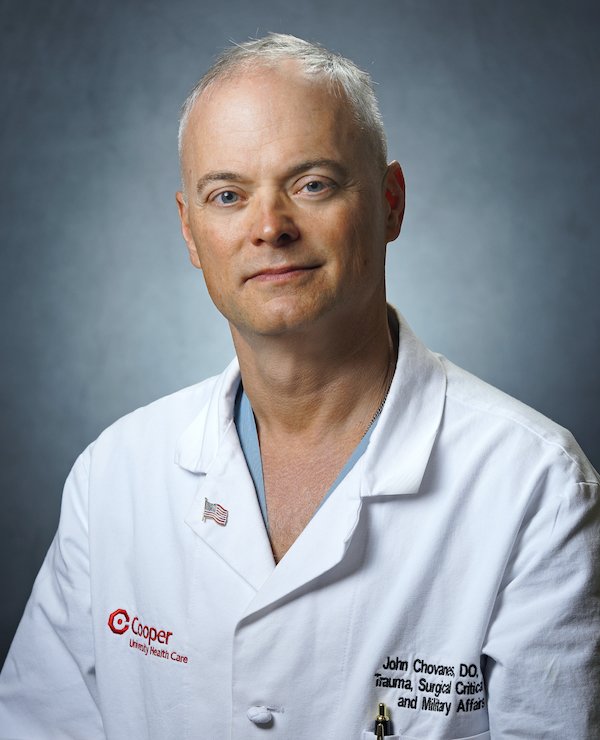

Dr. John Chovanes, right, and Lt. Col. James Burhop. Both were surgeons with the 911th Golden Hour Offset Surgical Treatment Team attached to 7th Special Forces Group in Helmand province, Afghanistan, in 2020. Chovanes now trains Green Beret medics. Photo courtesy of John Chovanes.

John Chovanes swore into the Army Reserves in front of the Liberty Bell.

It seemed like the right move: He was a Philly kid, his dad was a veteran, and he was as patriotic as the next guy — maybe a little more than the next guy — so joining up seemed right, even though he had already graduated from medical school.

“I believed in the cause, and my dad was in the Army in the Korean War,” he says. “I thought it was a good opportunity, and I wanted to be a trauma surgeon. If I was going to talk the talk, I wanted to walk the walk, right?”

His recruiter was skeptical, though.

“I’ll never forget the recruiter,” Chovanes says. “He said, ‘Wars? There’s never going to be any wars.’”

It was June 2001.

Chovanes had never wanted to do anything but medicine, and the only medicine he wanted to do was the blood-and-guts, lifesaving stuff of emergency trauma care. As a teenager, he lied about his age to become an emergency medical technician, and within a few years, he was a civilian flight medic.

“I had been very experienced in the pre-hospital world,” he says. “I’ve always had a yearning for the field.”

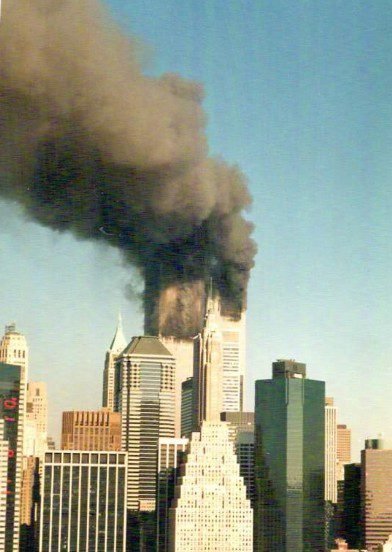

He went to medical school in Philadelphia and after the Liberty Bell, jumped into the first weeks of a surgical residency in the city. In the fall of 2001, he was finally a doctor and beginning to learn to be a surgeon, but with years of study ahead. His first days off were to be in September, and he called a friend, a Vietnam helicopter pilot, about a fishing trip. Halfway through the conversation, one of them was watching TV. “Something happened at the World Trade Center.”

As he watched, Chovanes was thinking neither of medicine nor the Army. He was thinking of history.

“This is the equivalent to Pearl Harbor,” he says. “I’m not going to be fishing when there’s this disaster.”

He climbed in his truck and drove north, listening to New York City radio stations.

“As I head toward Allentown, it was getting worse,” he remembers. “I heard Rudy Giuliani. He was calling for medical people. And I was like, ‘Oh, there’s my ticket.’”

From rural Pennsylvania, he drove directly into Manhattan and talked his way past some police checkpoints. He remembers following a Ryder truck through an empty tunnel, but he doesn’t recall whether it was the Holland or Lincoln tunnel.

“I ended up with some folks on an ambulance at an intersection,” he remembers. “It was surreal. You have these arc lights, and I’m just at the edge of one of the destroyed areas. And there was a Burger King there. And a guy just serving food for anybody who needed the food.”

Then word filtered out between first responders: “There’s a Port Authority cop trapped in there — well, there’s two of them — and I’m right there at the corner where two of them are trapped.”

Chovanes found his way through buried rubble, where a string of dozens — perhaps hundreds — of cops were lined up, creating a path to the site of their trapped colleagues.

“A single-file line going into this abyss,” Chovanes remembers.

Among them, Chovanes was stunned to see a face from back home. Louis Lombardi was in his 15th year as a New York City detective on 9/11, but he’d grown up on the same block as Chovanes in Philadelphia.

With Lombardi, Chovanes moved down the file of police, into the gloom.

“What John did was truly heroic,” Lombardi later wrote. “I was there because I had to be, he was there because he volunteered — courage above and beyond.”

Finally, they reached the hole in which Port Authority police Officer John McLoughlin was buried, with another, Will Jimeno, nearby.

“We would kind of do a combat crawl to get to where he was buried flat, up to his shoulders, at the end of a long little tunnel,” Chovanes says. “We would start IVs or administer medicine, then come out.”

Still, McLoughlin was trapped under hundreds of tons of debris. Moving him, Chovanes figured, meant one thing.

“Frankly, I got ready for amputation,” he says.

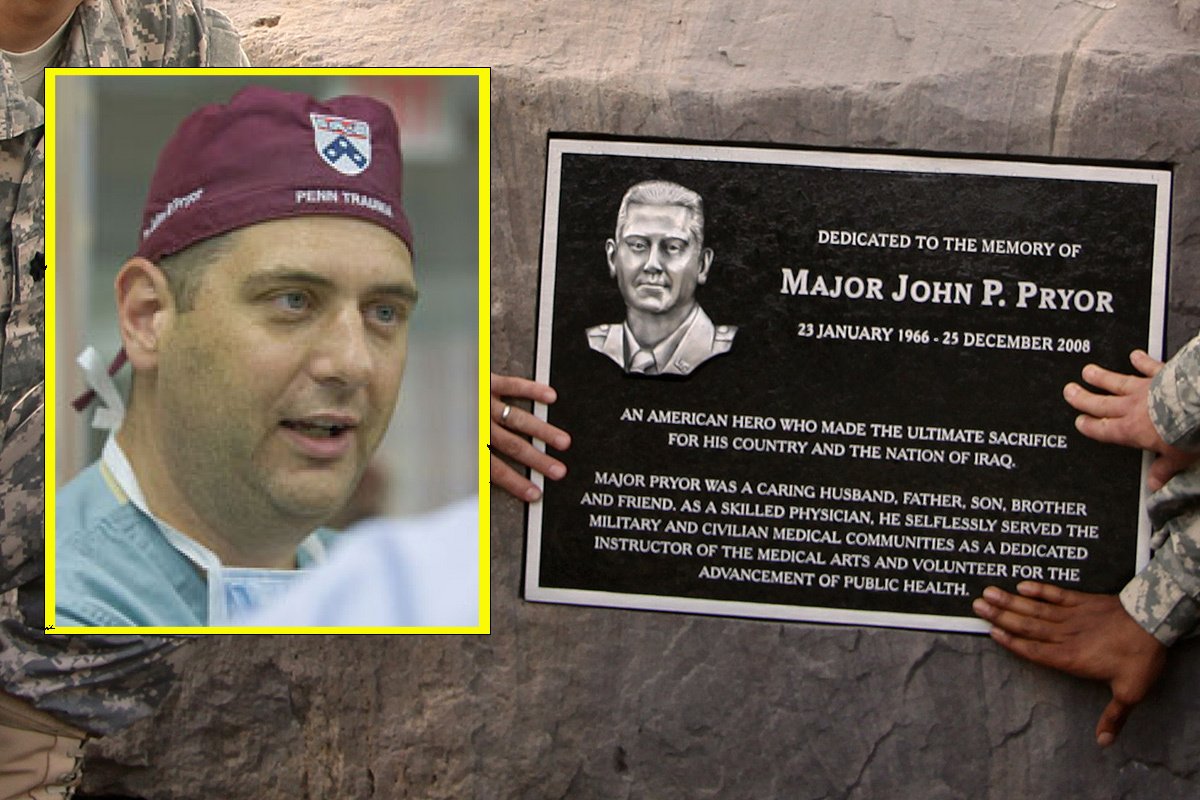

Throughout the night, Chovanes called out his medical reports and requests for supplies to another doctor standing on the surface. As they talked, they heard in each other’s voices a familiar Philadelphia accent. The voice was that of John Pryor, a man Chovanes had never met, though, looking back, it’s hard to figure how they avoided each other for so long. Both were Philly trauma surgeons. Both started as street paramedics. Both were in Philadelphia when the towers fell and immediately drove to New York.

“We both showed up and looked for some way to help,” Chovanes says. “I guess I’d gotten farther into the wreckage because I follow the rules a little bit less than John.”

But as Chovanes called back out for supplies and medicine, the two immediately clicked.

“I’d say we need this and that, and you don’t want someone questioning ‘Why do you need this or that?’” Chovanes says. “You want them to say, ‘What do you need, and how much of it?’”

At one point, Chovanes says, he believed the trapped cop might vomit, so he asked for a powerful anti-nausea drug called Compazine. He also asked for a surgical tool called a Gigli saw used in amputations. Within minutes, both arrived, passed from Pryor down the line of hundreds of police and first responders to Chovanes.

“Down this long line comes this little 5-millimeter vial, handed by 400 arms of love,” Chovanes remembers.

It took 22 hours, but with Chovanes providing medical care, rescuers eventually freed McLoughlin, the last person found alive in the World Trade Center rubble. There was no amputation.

“I’ve got to make very clear that I wasn’t doing the digging,” Chovanes says.

Within months, Chovanes and Pryor reconnected in Philadelphia and forged a bond that would change each other’s lives.

Pryor was a trauma surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania. Bonded by their 9/11 experience, Pryor became a mentor to Chovanes through first his training and then a fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania.

And while Chovanes fell in behind Pryor’s surgical career path, Pryor took the same path Chovanes did into the Army. At 38, he joined the Army Reserve as a trauma surgeon.

Chovanes first deployed after his residency, in 2007, working in a field hospital outside Tikrit, Iraq. Some days were slow; other days, the bays would fill with 20 trauma cases. Sometimes they worked with locals, children, and even injured insurgents.

“That really builds bridges,” Chovanes says. “I call it hearts and minds, but that should be pretty common, and I’m surprised that we had to relearn that lesson. I dealt with a lot of injured children there because whether they pick up something inadvertently or something happens, they’re caught in the crossfire. So we’re like Cooper Hospital in Camden. Whoever comes through the door, we help them.”

By December 2008, Chovanes was back in Philadelphia, considering whether to continue in the Army. Pryor was already back in Iraq.

On Christmas morning, the phone rang — a mortar had exploded outside a field hospital in Mosul, killing Pryor. He was 42 years old.

More than 2,000 people attended Pryor’s memorial at Philadelphia’s Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul. When it came to Chovanes’ turn to memorialize his friend, he said, “He just couldn’t tolerate living his comfortable, blessed life here, knowing that we had young men and women protecting all of us without them getting the best care.”

Chovanes served five more overseas rotations, working with Green Beret medics and hooking up with the Special Forces field hospital at Forward Operating Base Salerno in Khost, Afghanistan. Later, he manned a Golden Hour Offset Surgical Team, or GHOST, a specialized, mobile surgical team that aims to reduce the time between a combat injury and surgical treatment to less than an hour — a massive leap forward in the special operations community.

“The incredible warriors in Special Forces, these incredible men and women, with the integration they have, they were doing something that would take the civilian world 10 years. These men and women did it in 10 days,” he says.

Today, Chovanes oversees training for future Green Beret medics and other SOF medical troops in his emergency room at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, New Jersey. The hospital, along with the city’s ambulance services, hosts the future medics in monthlong clinical rotations as the capstone training to the Special Operations Combat Medic course at Fort Bragg. All Green Beret medics, flight medics with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, Navy SEAL corpsmen, and other special operations medics pass through Cooper.

“It’s good having the civilians working with the military,” Chovanes says. “They’re the same kind of people. They go wherever the action is.”

This article first appeared in the Fall 2021 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “Surgical Extraction.”

Read Next:

Matt White is a former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. He was a pararescueman in the Air Force and the Alaska Air National Guard for eight years and has more than a decade of experience in daily and magazine journalism.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.