West Point’s First Black Graduate Was Born a Slave, Led the Buffalo Soldiers

Lt. Henry O. Flipper in his US Cavalry uniform, circa 1877. Photo courtesy of the US House of Representatives Committee on Military Affairs.

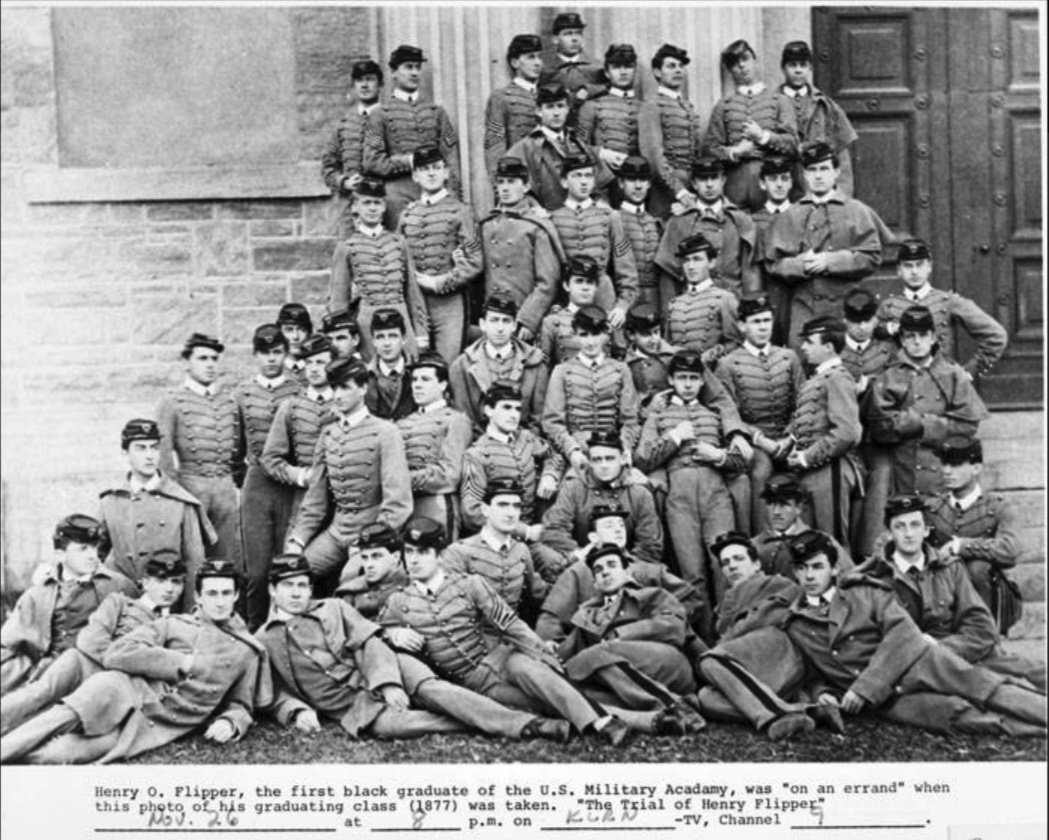

Long before Henry Ossian Flipper became the first Black American to graduate from the US Military Academy at West Point, he was born into slavery. His parents belonged to a Georgia slave dealer until the Emancipation Proclamation freed his family.

Following the Civil War, Flipper briefly attended Atlanta University, where he met Georgia Rep. James C. Freeman, who nominated Flipper to New York’s West Point in 1873.

He was a free man when he arrived at West Point, but he wasn’t welcomed. Flipper’s memoir, A Colored Cadet at West Point, detailed the isolation and cruelty he endured. “In less than a month they learned to call me ‘nigger,’” he wrote.

Though insulted and harassed by white classmates all four years on campus, he became the school’s first Black graduate in 1877.

From his first assignment at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, draining malaria ditches, Flipper eventually moved on to be with his assigned unit at Fort Concho, Texas. There, Flipper became friends with the first officer to whom he was assigned, Capt. Nicholas M. Nolan, an Irish immigrant and career soldier.

Nolan appointed Flipper as his adjutant to A Troop, part of the Buffalo Soldiers 10th Cavalry Regiment, a position traditionally given to white officers. It would be the first time in American history that a Black officer received a command position.

Nolan and Flipper frequently dined together, and Nolan eventually invited Flipper to board in his home alongside his own family. Flipper became good friends with Nolan’s young sister-in-law, Mollie Dwyer. He spent much time with Dwyer, and the two frequently exchanged letters.

Though Dwyer and Flipper were not destined to be together, the growing jealousy from other white officers resulted in a smear campaign against Flipper’s reputation.

It wouldn’t be the only time.

Flipper spent time at Fort Concho outside San Angelo, Texas, and then moved with the 10th Cavalry to Fort Elliott in the Texas panhandle. There, Flipper assisted in a jailbreak from a corrupt marshal’s jail, fought in skirmishes — including the Apache Wars — and established supply and telegraph lines to local pioneer communities.

Cutting his teeth in combat with Nolan, Flipper proved to be an excellent officer. But in 1880, Flipper was transferred to Fort Davis in West Texas, becoming the post quartermaster and commissary officer.

Fort Davis came under the command of Col. William “Pecos Bill” Shafter in 1881. Shafter was notorious for mistreatment of officers he disliked, and he dismissed Flipper of his post as quartermaster almost immediately. Flipper still conducted the de facto duties of the position, which included the record-keeping of the quartermaster’s safe, now stored in Shafter’s office.

In the course of his duties, Flipper found roughly $2,000 missing from the safe. Knowing he’d be blamed if he came forward with the knowledge, Flipper hid the discrepancy until he could cover it on his own. It didn’t matter, though — Shafter was counting on Flipper’s reticence to come forward and had Flipper arrested on Aug. 13, 1880, on charges of embezzlement.

Fipper looked as far as Boston and New York to find a lawyer who would represent him, but few seemed interested, even among Black lawyers. At the last minute, Capt. Merritt Barber, a white officer from the 16th US Infantry, stepped in. Barber proved that Shafter contradicted himself multiple times and was able to convince the court-martial panel that Flipper’s only offense was being a clumsy bookkeeper. The evidence was thin, and Barber had several witnesses testify to Flipper’s integrity.

A court-martial cleared Flipper of embezzlement but convicted him of “conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman.” He was dishonorably discharged from the Army, a punishment more severe than what white officers typically received.

After the Army, Flipper became a successful engineer, author, and Secretary of the Interior special envoy to Mexico, retiring to Atlanta in 1931.

Today, the West Point Henry O. Flipper award is granted to cadets who show strength in rising above harsh adversity.

At a White House dinner in February 1999, President Bill Clinton celebrated the 90th anniversary of the NAACP and delivered some news to the audience: “Just before I came over here tonight, 117 years too late, I awarded a pardon, posthumously, to Lt. Henry Flipper.”

Read Next: The Legend of Jim Capers: The Hero Who Never Was

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.