Little Americas: The Enclaves of Western Culture in Post-WWII Germany

To the casual listener, Ramstein Air Base might sound like a heavy metal compound. It’s not, although it is full of heavy metal. Located near Kaiserslautern (K-town, to Americans), Ramstein is an American Air Force base that began construction in 1949 and has been in operation since 1953. Its current host unit is the 86th Airlift Wing, but the base itself has served as a haven for American and Allied gunships and civilian transport for over 60 years.

At the end of the Cold War there were more than 800 similar American military bases scattered throughout the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin. Their construction and maintenance required incredible amounts of manpower; over 570,000 American military personnel, their families, and civilian workers lived and worked within these compounds. It was, for a time, their life and their home.

Following the end of World War II, massive numbers of American troops remained in Allied-occupied Germany. Their job was to determine what would become of the country, to assist in the rebuilding of Europe, and, as soon became apparent, to erect a bulwark against Soviet expansionism.

In the wake of the conflict that had come bearing down on Germany like a tidal wave, many military bases, residences, and even entire towns had been left ravaged and scarred. The American soldiers deployed to Germany used these opportunistic ruins as new forward operating bases, taking up residence in dilapidated barracks and hastily departed civilian buildings. From forgotten streets to old Luftwaffe airstrips to new bases entirely, the American military began a massive project of reconstruction in their former enemy’s state.

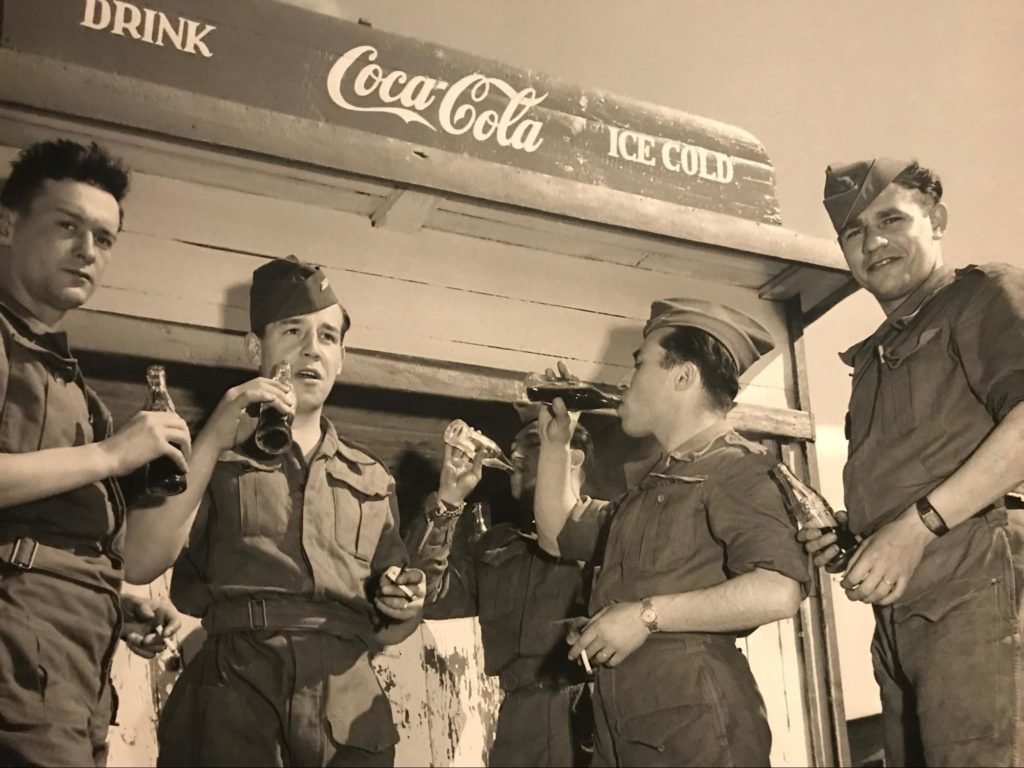

They brought with them not only bricks and steel, but blue jeans, cigarettes, jazz, and Coca-Cola. In their back pockets, they carried democratic ideals. Their way of life shone in stark contrast to both the autocratic horrors of the now-dead Nazi government and the novel threat of far-reaching communism in the East. To the German workforce with which these soldiers mingled and integrated, this lifestyle was both adored and abhorred.

However, “integration” is perhaps too strong a word. Both sides were cautious about the occupiers mixing with locals. Fraternization between U.S. troops and German women, for example, resulted in furious debate on both sides about what the rules of contact should be. As the Cold War began to materialize into something insipid, latent, but all-too real, the relationship between Allied military personnel and the local population was called into question.

Since the U.S. forces were needed to both prevent Soviet expansion and maintain power in occupied Berlin, it was decided that a conflict-free existence between Germans and Americans was the best course of action going forward. The idea was to maintain power with as little interference as possible. It was from this idea that the Little Americas began to form.

With such large numbers of troops stationed in bases across the country, its genesis was inevitable. These enclaves of American culture served two purposes: to provide U.S. military personnel with a sense of familiar nationality and normalcy, as well as to separate them from the local German population, much of which regarded the Allied occupation with annoyance bordering on ire.

These enclaves retained all of the mainstays of American culture at the time. Numerous facilities and establishments were erected, and local American goods were imported in droves. Soldiers and their families could live on these bases and experience the same, or at least a passable simulacrum of the, American way of life back home; they didn’t even need to learn German.

There were theaters showing the latest films, local clubs, salons, sporting grounds, restaurants, shops, churches, schools, hospitals, workshops, post offices, night clubs, and service facilities. The construction of these facilities became a crucial meeting point for American personnel, but it served the dual purpose of creating massive amounts of employment for a decimated German economy.

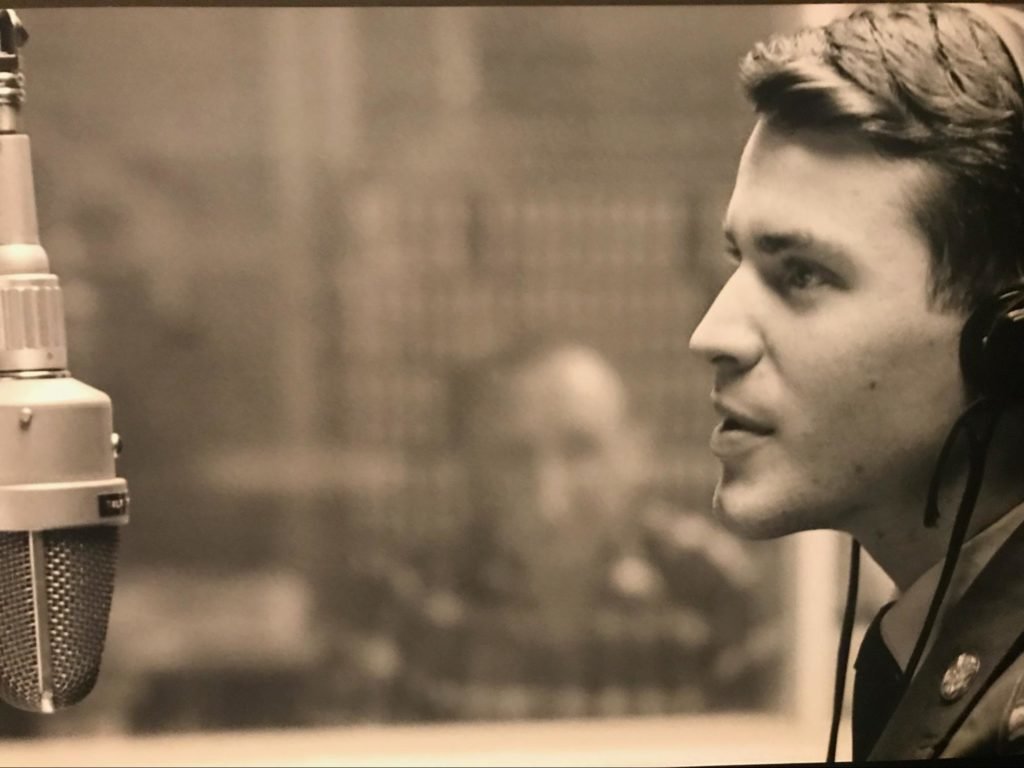

These bases even enjoyed their own radio station called the American Forces Network. The network still exists today and was used to broadcast news and entertainment to American forces stationed throughout West Germany and Europe.

The military provided almost everything the soldiers and their families needed, which meant that very little had to be obtained from local German towns. They received a number of different coupons and tickets that they could exchange for American goods at the local Post Exchange, or PX. When they did need to buy goods from local towns, they did so at an extremely favorable exchange rate, and so shopping locally — on the economy, as they called it — meant they earned a considerable bang for their buck.

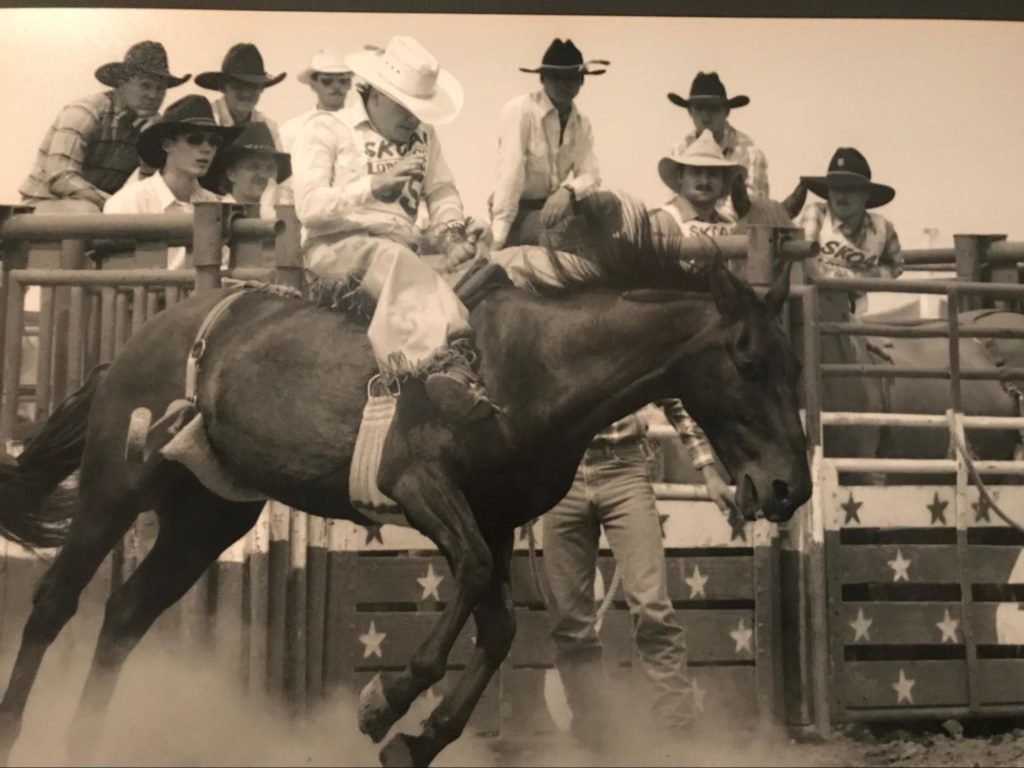

Days on the base usually began with some sort of sporting activity, after which soldiers were directed to training or toward whatever their work function within the military was. Children of military personnel attended the local American school. Affectionately self-named “brats,” they not only enjoyed an American education (albeit a military one) but were provided the chance to engage in American leisure activities. Football, dancing, and cheerleading were all common pastimes, and there were even opportunities to attend rodeos.

Photographer John Provan, who grew up on Sembach Air Base northeast of Kaiserslautern, remembers it well.

“As military kids — brats — we felt a common bond, and I spent a beautiful childhood growing up in the military,” he recalled. “On the airfield, we had everything we needed: workshops, a library, a large football stadium, a clinic, gym, bowling alley, a PX, and a commissary. Everything was there and for us kids, it was like paradise.”

As time went on, relations between the isolated American bases and the local population began to warm. Open House events such as Tag der Offenen Tür (Day of the Open Door) or Volksfeste (The People’s Festival) were organized on military bases to encourage interaction between German citizens and their American occupiers. The proceedings of these days usually included airshows, weapon and technology demonstrations, and a number of American public relations work, such as charity circles.

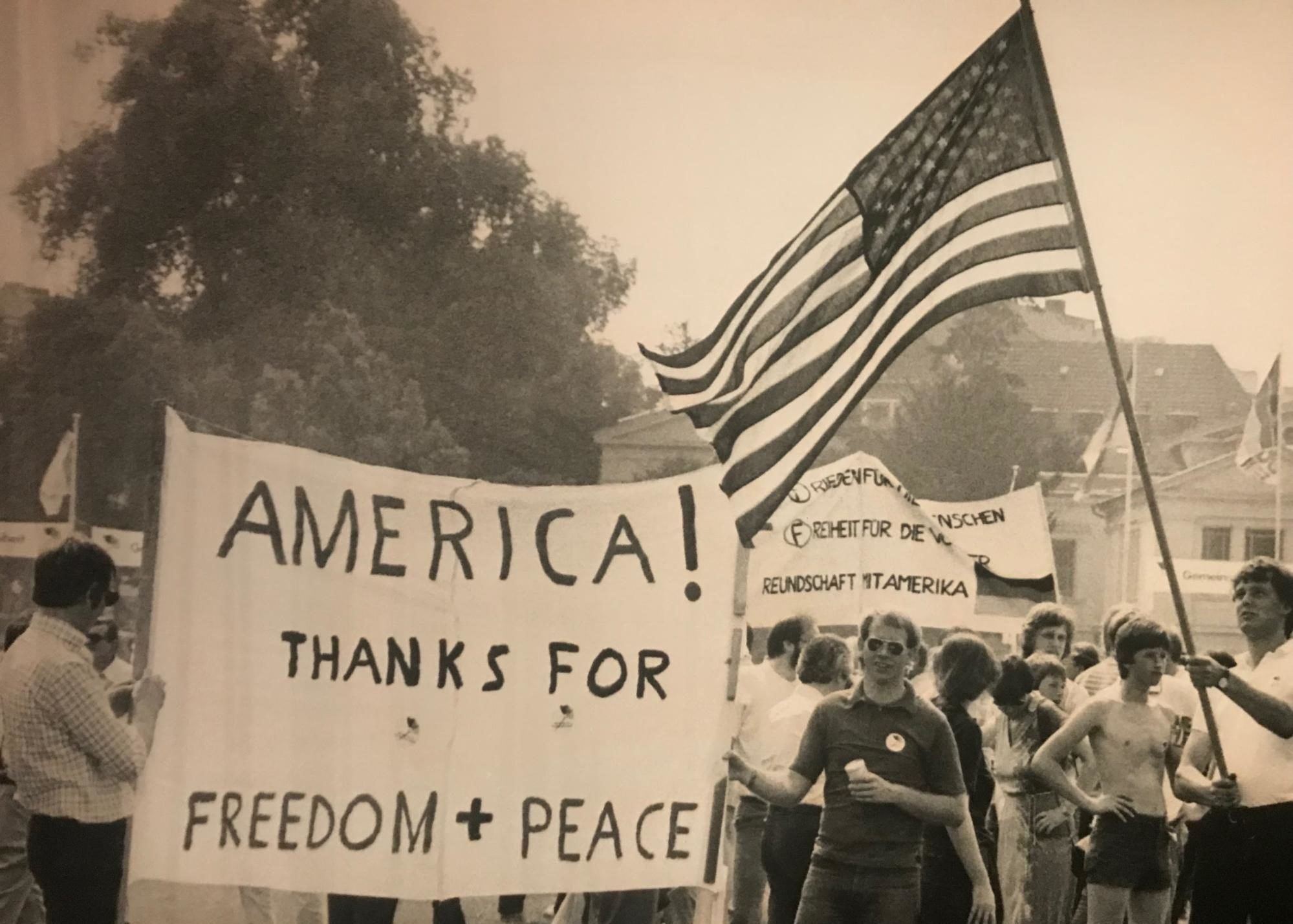

Not all of these interactions were positive, however. While many Germans welcomed American culture and the democracy that came with it, others still regarded them as occupiers and actively encouraged them to leave the country.

When American troops did eventually leave Germany, the void left behind by the military quickly became apparent. The massive infrastructure occupied by the Americans suddenly lacked the personnel to maintain it. These economic hearts were removed, and the arteries supplying the surrounding towns dried up.

However, the influence of American culture on Germany can scarcely be forgotten.

“The language, democracy, all the way down to the fast food, popular music, the sports, and the clothes,” Provan said. “It’s important to preserve the memory that the GIs left behind.”

But the Americans also took back parts of German culture.

“We took with us things like the Kindergarten, the Gemutlichkeit, the Oktoberfest, the souvenirs (Hummel figures and bier mugs), and Mosel wine. It was the stylized, beautiful world they took with them that these veterans still remember fondly.”

Martin Stokes is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. He hails from Johannesburg, South Africa, but currently resides in Germany. He has numerous bylines that cover a variety of topics. He moved to Berlin in 2015 and, while writing for numerous publications, is working assiduously at broadening his repertoire of bad jokes.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.