Soldiers carry an inflatable “tank.” Photo courtesy of Imperial War Museums.

The walls were fortified with sandbags, the machine-gun nests were loaded and ready, and the best-trained Wehrmacht units waited for the anticipated invasion of France. The Nazis had reinforced the Atlantic Wall along the coast of Pas-de-Calais, sure that the invasion would come from the white cliffs of Dover in the distance.

Germany’s 15th Army was ready with more than a million men. According to the National WWII Museum, the Nazi force was “enough to man 58 divisions.” They just were in the wrong spot.

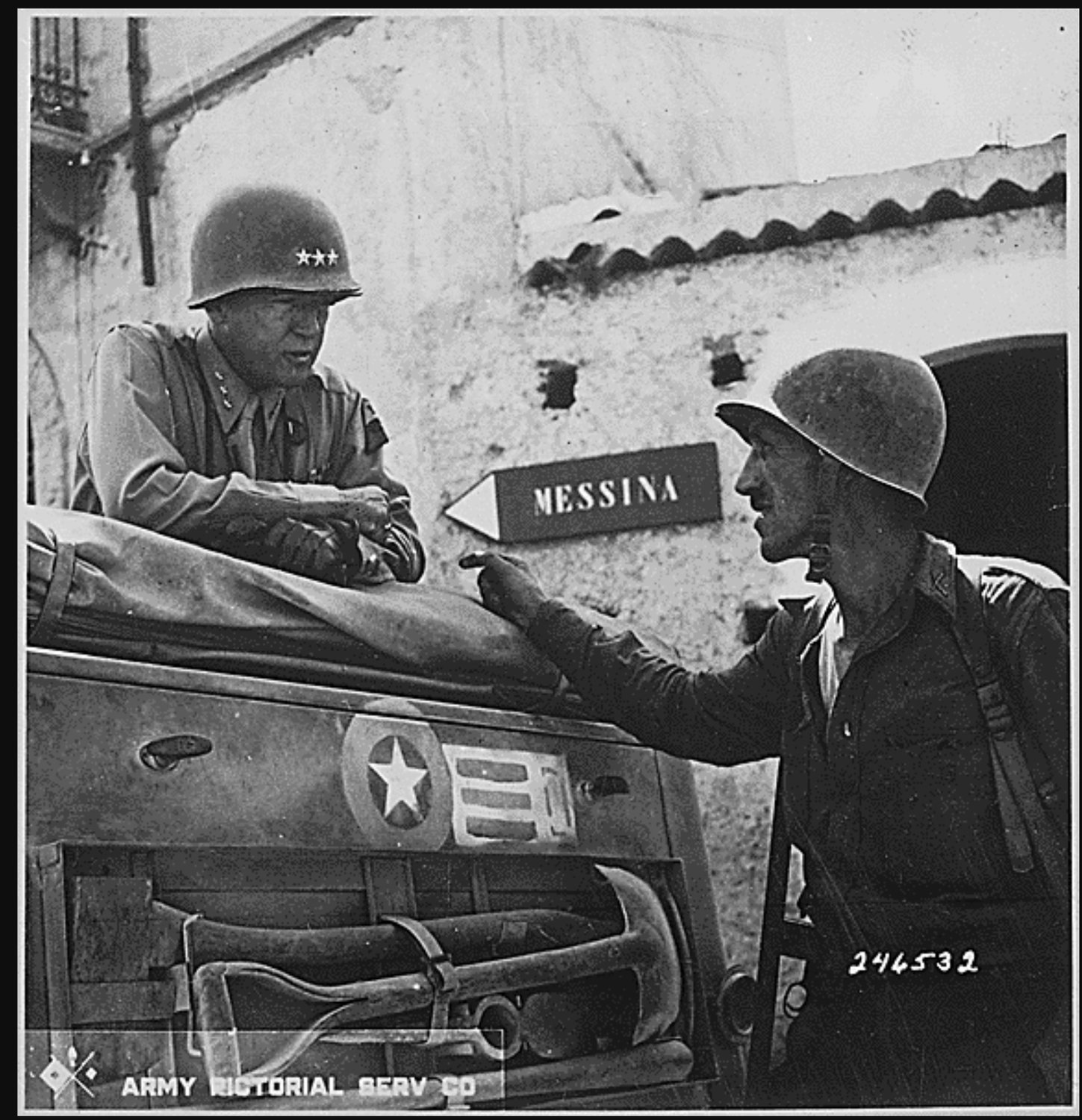

In fact, the Germans had fallen for an elaborate ruse. Their folly was attributed to a joint operation that used balloons, wooden props, a fake army led by US Army Gen. George S. Patton, and a tangle of misinformation laid by talented double agents.

The theaterwide subterfuge was called Operation Fortitude.

In the months leading to D-Day on June 6, 1944, Fortitude convinced the German High Command that a large-scale Allied attack was going to come from England’s southeastern corner, near Dover, to attack the region around Pas-de-Calais. It was a reasonable assumption.

The Strait of Dover is just 18 miles wide, the narrowest point of the English Channel. The English fled across the same stretch during the early war evacuation at Dunkirk (the Channel Tunnel spans the same gap today). On a clear day, the white cliffs can be seen from French soil. But the Allies actually planned to land at Normandy, 150 miles to the west, so tricking the Germans into defending the wrong stretch of coastline was seen as vital to Operation Overlord’s success.

Fortitude South

Fortitude South, called Quicksilver by the Americans, involved the use of false equipment, Patton’s fake army, and a handful of shift workers in tunnels beneath an English castle. The Allies positioned inflatable “tanks,” fake camps full of fake soldiers, and fake landing craft around the countryside of Kent, all for German spy planes to photograph.

A team of radio operators working diligently in tunnels below Dover Castle sent encrypted around-the-clock radio signals for the Nazis to intercept. The radio signals indicated cold-weather problems, weather reports for the North Sea, and equipment transfer and supply information for a rapidly growing fake army. False marriage announcements were posted in newspapers in and around towns in the countryside.

German intelligence would eventually believe 20 divisions of troops, both American and Canadian, were massing in Kent.

The units under Patton’s notional command — the First United States Army Group (FUSAG) — were real units, all known to the Germans, but were not located in Kent. Patton was touring the countryside, and he made sure the Nazis knew it.

Patton’s presence in and around Kent was a key part of the ruse. The German High Command feared Patton above all other Allied commanders. The Nazis considered him to be both clever and a loose cannon, and with Patton at the helm of the faux operation, German intelligence was convinced the rumor had merit.

English historian Joshua Levine, author of Operation Fortitude, states that “Patton’s actual job as FUSAG’s notional commander consisted mainly of traveling around southeast England (where the FUSAG units were supposedly based), publicly saying the right things and keeping the pretense going.

“Describing himself as a ‘goddamned natural born ham’ who enjoyed ‘playing Sarah Bernhardt,’ he wrote in a letter to a friend: ‘I had some very interesting trips while I was working as a decoy for the German divisions, and I believe that my appearances had a considerable effect.’”

Fortitude North and Double-Cross

Based in Scotland, Operation Fortitude North used similar radio tactics as those in Kent, and also sent diversionary aerial reconnaissance patrols over Norway. The flights implied an imminent invasion of Norway by way of the North Sea, led by British Lt. Gen. Sir Andrew “Bulgy” Thorne.

In England, a counterintelligence ring was run by the so-called Twenty Committee, or XX, of Britain’s MI5 — hence “Double-Cross.” British intelligence was able to turn a number of German agents and insert a few British operatives into German circles of trust, so they all could relay false information to Berlin. Agents with code names such as Garbo, Brutus, and Snow spread false leads created to point the Germans toward Pas-de-Calais.

The success of Operation Fortitude meant Hitler’s best units were still waiting in early June, completely unaware that they showed up at the wrong party. When the 150,000 Allied troops invaded, they faced only about 50,000 Germans. Even as the Allies swarmed ashore on D-Day, many German units were held near Pas-de-Calais for two months, thinking the “real” invasion was still coming there.

Read Next: World War II Paradogs: The Dogs Who Jumped on D-Day

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.