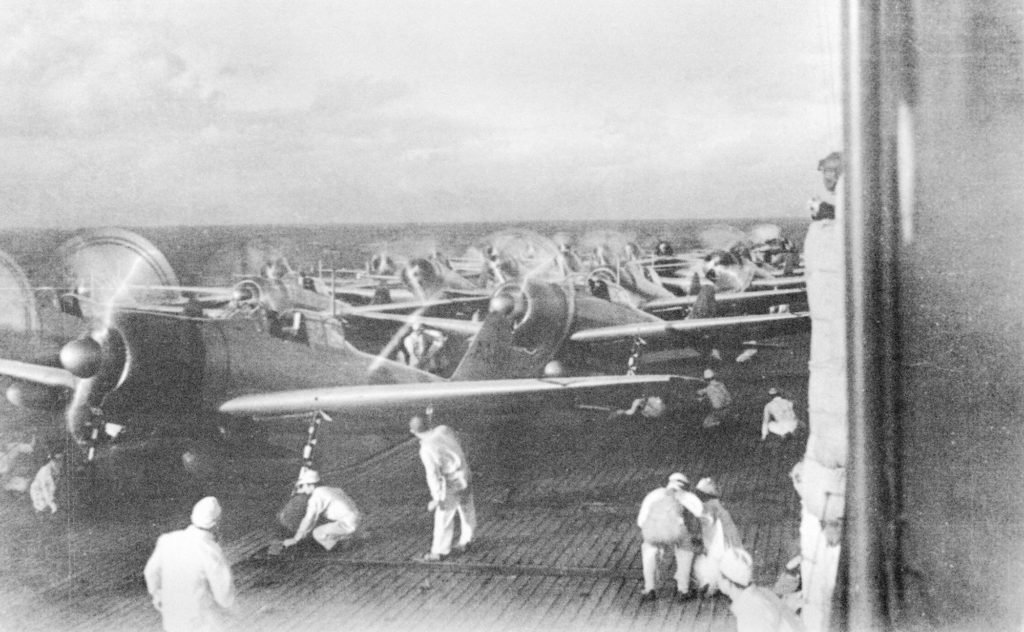

Photograph taken from a Japanese plane during the torpedo attack on ships moored on both sides of Ford Island. View looks about east, with the supply depot, submarine base and fuel tank farm in the right center distance. A torpedo has just hit USS West Virginia on the far side of Ford Island (center). Other battleships moored nearby are (from left): Nevada, Arizona, Tennessee (inboard of West Virginia), Oklahoma (torpedoed and listing) alongside Maryland, and California. On the near side of Ford Island, to the left, are light cruisers Detroit and Raleigh, target and training ship Utah and seaplane tender Tangier. Raleigh and Utah have been torpedoed, and Utah is listing sharply to port. Japanese planes are visible in the right center (over Ford Island) and over the Navy Yard at right. Japanese writing in the lower right states that the photograph was reproduced by authorization of the Navy Ministry. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

The morning’s forecast determined by the U.S. weather station in downtown Honolulu was 73 degrees with partly cloudy skies and clear visibility — a typical Sunday on the Hawaiian Islands. The Honolulu Advertiser printed the headline, “F.D.R. Will Send Message to Emperor on War Crisis,” announcing the plans for the following day, Dec. 8, 1941, at a joint session of Congress. Before the newspapers made their morning rounds, a distant hum turned into a loud buzzing overhead — planes were in the air. All U.S. aircraft were grounded, and no training events were scheduled for the morning of the seventh of December.

At 7:53 AM, the first bombs dropped with devastating accuracy. “I was leaving the breakfast table when the ship’s siren for air defense sounded. Having no anti-aircraft battle station, I paid little attention to it,” said Marine Corporal E.C. Nightingale, recalling the next few minutes while aboard the USS Arizona. “Suddenly I heard an explosion. I ran to the port door leading to the quarterdeck and saw a bomb strike a barge of some sort alongside the Nevada, or in that vicinity. The Marine color guard came in at this point saying we were being attacked. I could distinctly hear machine gun fire. I believe at this point our anti-aircraft battery opened up.”

Nearly two hours after Japan launched one of the most sensational surprise attacks the modern world had ever seen, questions arose as to how the United States could get caught sleeping. Why was there no warning? How did the Japanese cross thousands of miles of open ocean without being detected? How did the Japanese use deception to not raise suspicion of their plans to attack the West? The answers were not overt — decades earlier, a behind-the-scenes silent intelligence war had begun, and it continued to develop as the day that will live in infamy drew nearer.

The turn of the 20th century saw the Russian empire, a significant world power, defeated in battle against the Japanese during the Russo-Japanese War. Through 18 months of fighting, Japan’s shock victory earned their place as a military power in the international arena. During World War I, the Japanese honored their 1902 British alliance against the Chinese providing the Brits with naval support. As a strategic ally, Japan expected more recognition, and soon became one of the five countries — Britain, France, the USA, Italy, and Japan — invited to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

“As part of the post-war treaty, Japan asks the Allies for their citizens to have free immigration to western countries like Australia and America,” says the narrator from the Netflix documentary “Greatest Events of WWII in Color.” Their request was denied, and the Japanese returned home disrespected but optimistic. This optimism vanished when President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned Japanese immigrants from obtaining U.S. citizenship. The U.S. military publicly distanced themselves from Japan but quietly monitored their naval strategy.

Naval cryptologists from the “On-the-Roof-Gang” — a nickname bestowed upon those who trained in secrecy inside a wooden structure on top of the Navy Headquarters Building in Washington — were instrumental in decrypting Japanese cipher machines and messages during the 1920s and 1930s. They broke “Red Book,” the code for the Japanese navy’s fleet, and they recovered the superencipherment for its replacement “Blue Book.” Although the Japanese weren’t initially aware of the U.S. signal and communication interception teams, they advanced their systems by June 1939, rendering the code for Blue Book useless.

The On-the-Roof-Gang’s most notable achievement came post-Pearl Harbor when codebreaker Joe Rochefort cracked JN-25. Information gathered had indicated that the target for the next Japanese attack was Midway Island. This was a turning point in World War II, with the Pacific Fleet prepared to fight the first aircraft carrier-versus-carrier battle in history. Despite the eventual success, they failed to discover the plans to attack Pearl Harbor, though it wasn’t entirely their fault.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, a pioneering mind with a Harvard education, understood the importance of naval aviation. He altered a two-decade defensive naval strategy into an offensive one, using aircraft carriers as his means to launch a surprise attack against the U.S. Pacific Fleet. A daring and courageous act of war had to be executed perfectly if they had any chance of success. In January 1941, plans were set in motion for a sneak attack on Pearl Harbor.

Yamamoto first had to address a multitude of problems: torpedos that could drop in shallow water, radio silence during their 4,000-mile journey across the Pacific Ocean, and a means for effective and actionable intelligence-gathering on the ground.

The torpedo problem was solved by attaching custom wooden fins to the tails of the torpedos that the Japanese dropped from their planes. This ensured the koku gyorai, or “the thunderfish in the sky,” could strike naval vessels without getting stuck in the harbor’s mud. In November, a month before the attack, Japan’s Denial and Deception (D&D) deceived the Americans in the Philippines and Hawaii by influencing their perception of the location of their aircraft carriers in the Sea of Japan. Their radio intelligence secured their attack plan was a step ahead of American intelligence while at sea because they never suspected anything out of the ordinary.

The third problem was establishing ground assets inside the U.S. — a problem to which they did not have trouble finding a solution.

The Japanese spy network inside the U.S. was vast, and the threat of sleeper cells was very real. The U.S. Navy’s “Magic” program uncovered the cables of Japanese attachés and learned the Japanese had agents in the U.S. Army, defense industries on the West Coast, and across every major city in America. However, their most prized intelligence officer acted alone in Hawaii.

Yoshikawa heard the first bombs fall and listened to a weather broadcaster from Tokyo over his shortwave radio, who announced, “East wind, rain,” the signal for war with the United States.

Tadashi Morimura joined Japan’s naval intelligence in 1936. “Since I had been studying English, I was assigned to the sections dealing with the British and American [sic] navies. I became the Japanese navy’s expert on the American navy,” he wrote. “I read everything; diplomatic reports from our attachés, secret reports from our agents around the world. I read military commentators like [New York Times military affairs editor] Hanson Baldwin. I read history too. Like the works of Mahan, the famous American admiral.”

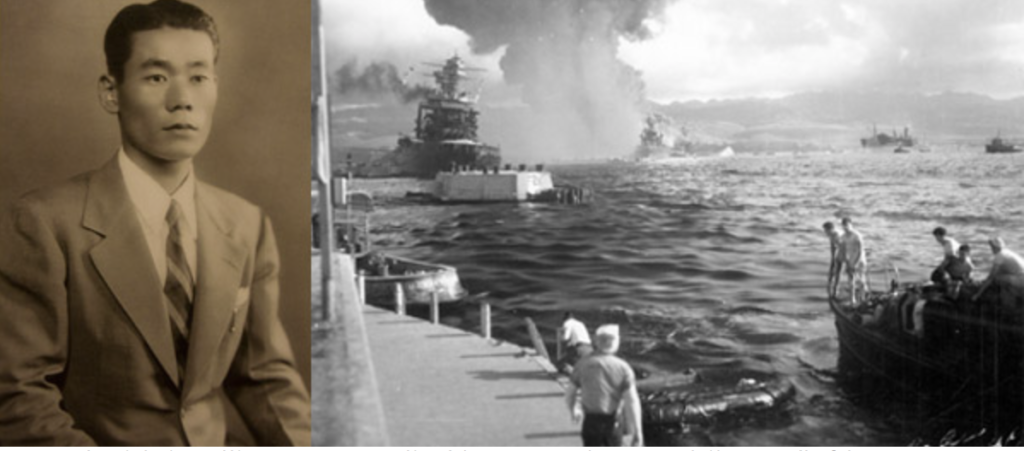

Tadashi Morimura posed as a diplomat on behalf of the Japanese Consulate in Honolulu, Hawaii. The office of the Coordinator of Information (COI), the precursor to both the OSS and later the CIA, missed the fact that there was no listing of a Tadashi Morimura in their Japanese foreign registry — an important fact considering it was a false name.

Morimura’s real identity was Takeo Yoshikawa, a naval officer tasked with a top-secret espionage mission to gather daily intelligence on defense systems, geographical maps, naval mobilizations, and important developments on Pearl Harbor. He was advised to tell no one because of the risk.

His pocket litter didn’t raise awareness because he hid in plain sight, growing his hair long like other Japanese natives who lived on the island. It was a common practice that Foreign Service Officers (FSO) all over the world used to remain invisible while in the field.

“From my office window I could not see the lights of the Navy Yard, but I could picture them in my mind’s eye as I could the varied gleams of light across the waters of Pearl Harbor, gleams which meant that 39 U.S. warships were assembled there—only the carriers and a small escort force under Halsey were at sea that night,” Yoshikawa wrote in 1960. “I knew all this with certainty since my whole being had been dedicated to a concentrated study of the U.S. Pacific Fleet for the last seven years, and since I alone had been in sale [sic] charge of espionage for the Imperial Japanese Navy at Pearl Harbor for the last eight months.”

He used diplomatic immunity, which allows the same access as any tourist, and picked up leisure activities that provided cover for his true intentions. “I habitually rented aircraft at the John Rodgers airport in Honolulu for my surveillance of the military airfields, and walked nearly every day through Pearl City to the end of the peninsula where I could readily survey the airstrip on Ford Island and battleship row in Pearl Harbor,” he wrote. “Another excellent collection aid I developed stemmed from my boyhood prowess in swimming. I made many observations on underwater obstructions: tides, beach gradients, and so forth while on swimming expeditions along the fine beaches of the Islands.”

The Sunchoro Teahouse, a Japanese restaurant on a hillside overlooking the harbor, was a welcomed vantage point. He collected information from local island girls, talkative hitchhiking navy officers he probed while he gave them a lift, and observed peculiarities with his own two eyes. Yoshikawa sent detailed messages in diplomatic code back to Tokyo. Ten days before “X-Day,” Lieutenant Commander Suguru Suzukinow Rear Admiral arrived in Honolulu disguised as a ship’s steward. He carried a tiny piece of paper rolled into a ball with 97 questions on it.

Yoshikawa determined that Sunday was the best day for an attack, he knew the precise blueprints to military airports from the aerial photographs he took while piloting his plane, and he had taken great risks in the preceding months to have the means to answer the majority of the questions.

In order to discover if the U.S. Navy had anti-submarine nets, he impersonated a Filipino laborer. Dressed in an aloha shirt, he walked barefoot near the harbor’s electric fence entrance and was nearly shot by a sentry. Aside from the detailed photographs he took by plane, Yoshikawa never wrote anything down to avoid a paper trail. Only when he returned to the Consulate would he take the information he had memorized and transcribe it into code.

The intelligence stage was set and the plans were finalized knowing the U.S. was still largely in the dark. “If Japan goes to war with the United States, Germany will immediately follow suit,” William Donovan, the Coordinator of Information, wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt on Nov. 13, 1941, describing the summarization of what Dr. Hans Thomsen, a German diplomat, relayed to Malcolm Lovell. “The United States has no effective way to wage war in the Pacific. It could not denude the Atlantic to place full fleet power in the Pacific.”

Yoshikawa’s final message received by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagum aboard the Japanese flagship aircraft carrier Akagi, read, “Vessels moored in harbor: 9 battleships; 3 class B cruisers; 3 seaplane tenders, 17 destroyers. Entering harbor are 4 class B cruisers; 3 destroyers. All aircraft carriers and heavy cruisers have departed harbor…. No indication of any changes in US Fleet or anything unusual.”

Yoshikawa heard the first bombs fall and listened to a weather broadcaster from Tokyo over his shortwave radio, who announced, “East wind, rain,” the signal for war with the United States. He and members of the Japanese Consulate reacted and went into cover-up mode as they shredded and burned any files or evidence of espionage. The FBI questioned his involvement but lacked the evidence to prosecute, so he returned to Japan. His work as an intelligence officer was deemed a success that left 328 airplanes destroyed, 19 Navy ships damaged, and 2,403 Americans killed. Twenty-four hours later, Japan invaded Hong Kong, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines, and they seized oil from the Dutch Indies.

Pearl Harbor was one of the greatest gambles in military history, but against Yamamoto’s predictions, the devastation didn’t cripple the morale of the American people. Instead, it united a nation that had previously opposed the war. The United States surged battlefield necessities and recognized the need for paramilitary, intelligence, and special operations units, many of which began during World War II and have since evolved into the premier fighting forces in the world.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.