50 Years Later, Have We Learned Any Lessons From the Pentagon Papers Leak?

The Pentagon Papers were America’s first glimpse into why the Vietnam War was unwinnable. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Grunts in Vietnam, like those in most wars, didn’t really have a chance to ask why they were there. They spent their days hot and sweaty; carrying a rifle, bullets, water, grenades, and maybe a radio or medic bag; and patrolling, simultaneously hiding from and stalking the enemy.

But at home, questions were being asked about the war as early as the mid-1960s. Why was the US in Vietnam, and what would it take to come home? Could the US, in the end, win? And if not, the public began to ask, why keep fighting a losing battle?

In 1966, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara would never have believed that the war wasn’t even half over yet. The Gulf of Tonkin incident — generally understood as the United States’ point of full commitment to the war — had been two years earlier, and that came several years after President John F. Kennedy had sent advisers into Vietnam, a move unknown to the general public. But with the war now in full swing and the anti-war movement blooming in the US, McNamara, a businessman to his core, wondered how much longer the US should expect to be in Vietnam and — in cold business terms — whether the benefits outweighed the costs.

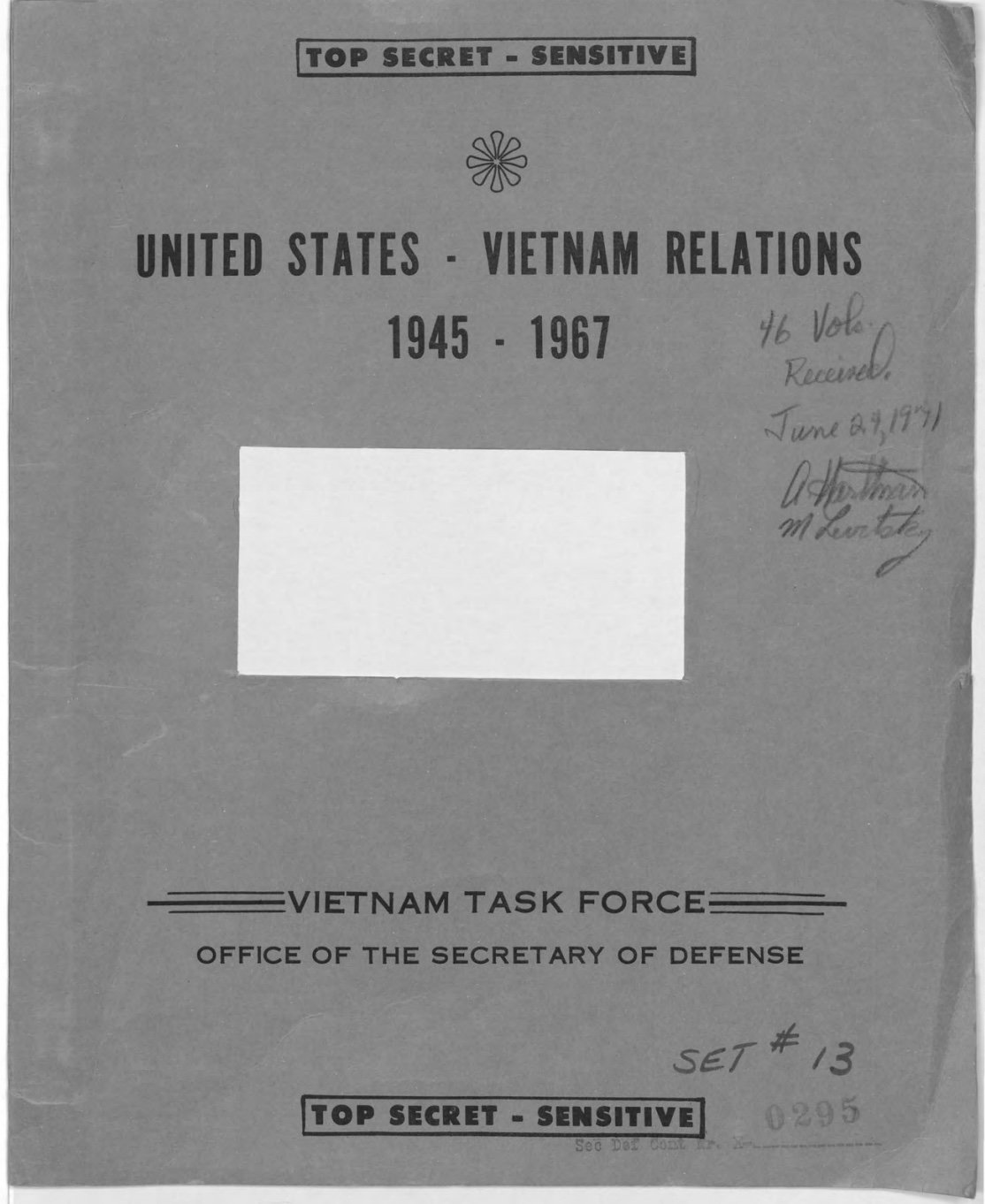

He commissioned a study in 1966 to examine the causes of the Vietnam War. He worked with professors from Harvard University and his close adviser John McNaughton, assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, to create a study of the road that led to war. The study was labeled “Vietnam Task Force,” and it was created without the knowledge of President Lyndon B. Johnson or Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

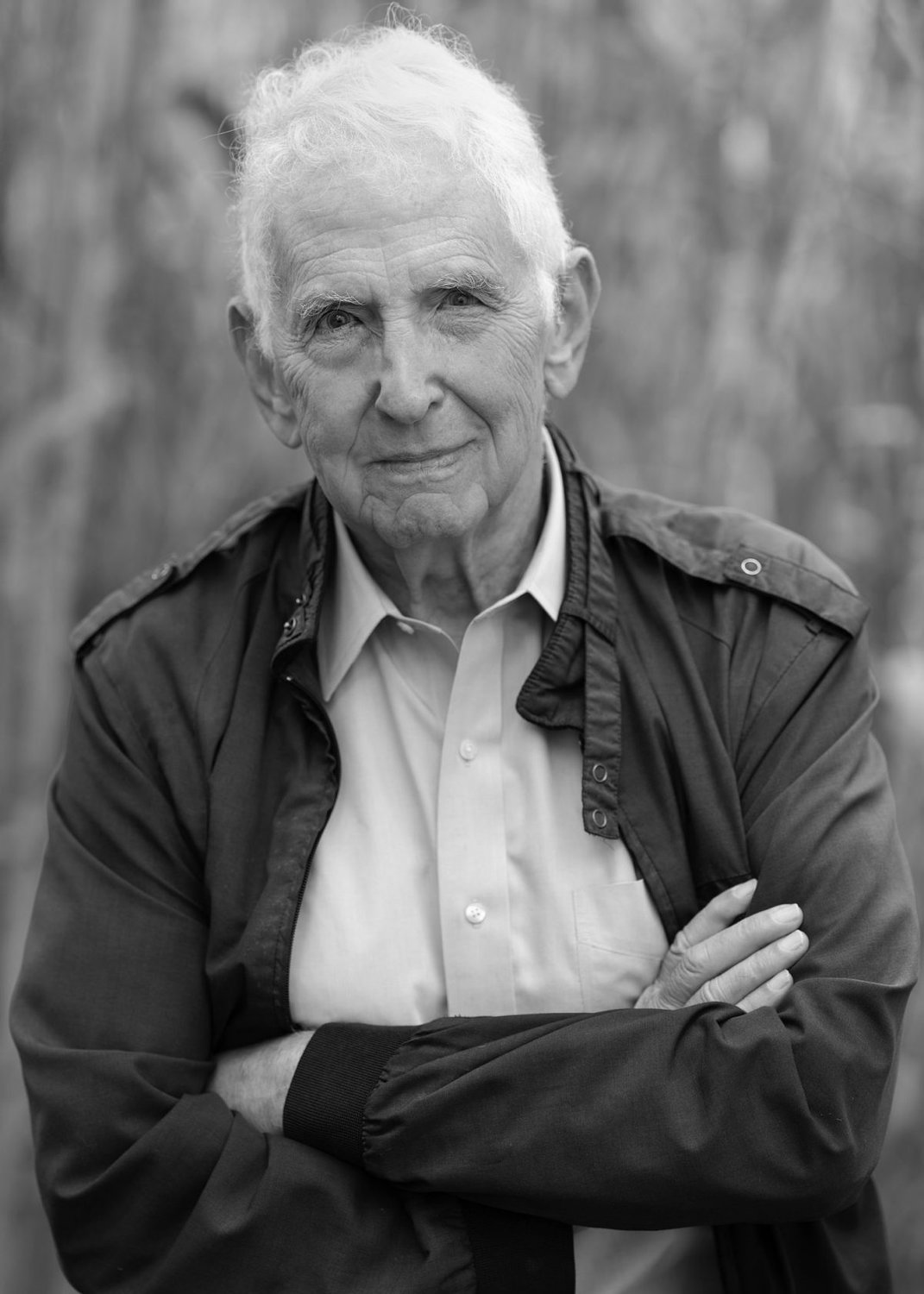

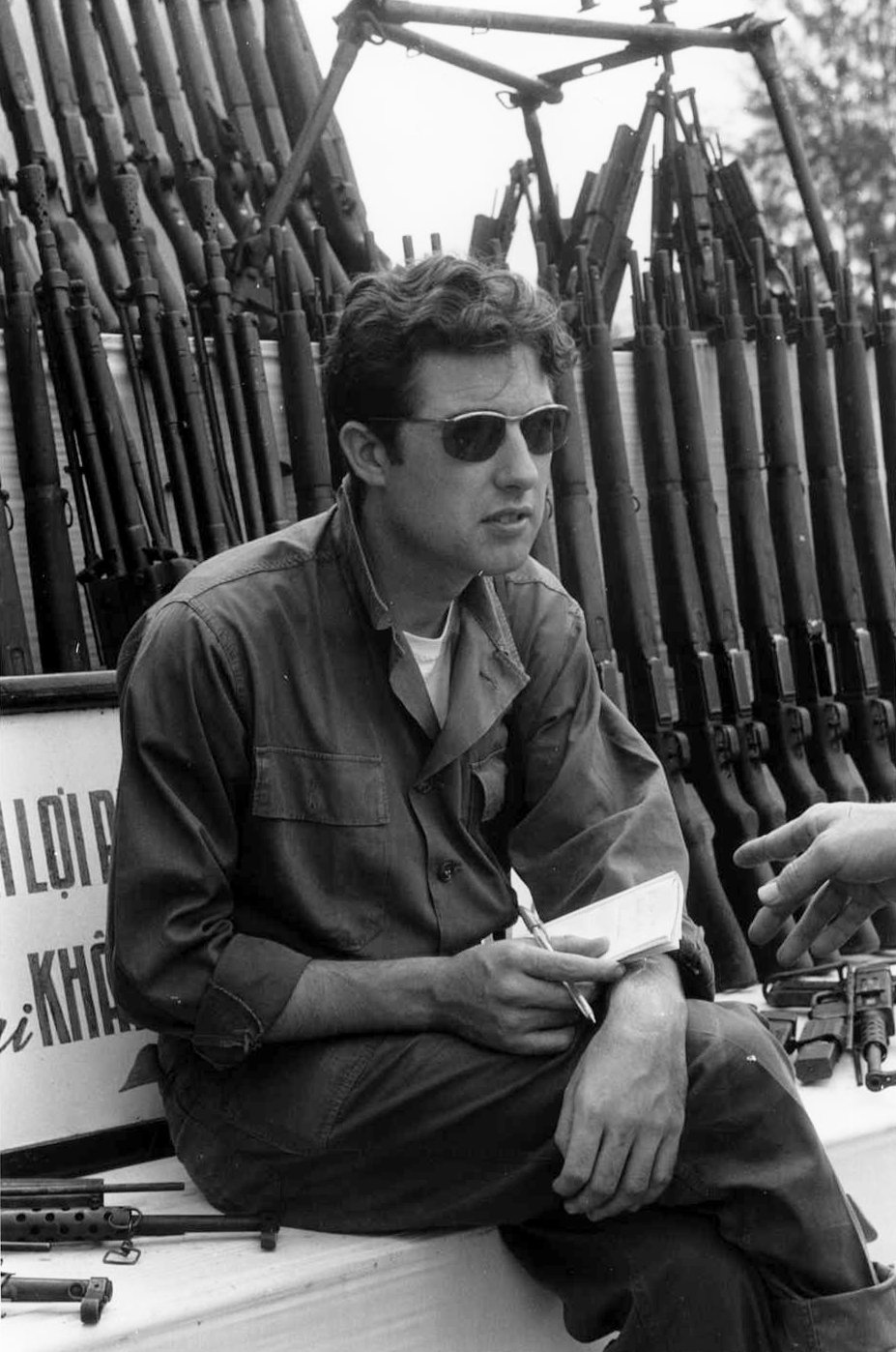

One of the companies McNamara enlisted was Rand Corp., a defense-industry firm that today would be called a think tank, filled with engineers and policy experts. One such expert was Daniel Ellsberg, a Harvard-trained economist who had once worked for McNamara and who studied nuclear game theory. Ellsberg was put on the Vietnam Task Force, which gave him access to all of the information the panel was studying as well as the final report. In the data, Ellsberg saw what many in the public believed but could not prove, and that which McNamara and others would not see: The US government had been sticking its hands in the Vietnam conflict for more than 20 years, knowing it would end in ruin. It would ultimately continue to do so until 1975.

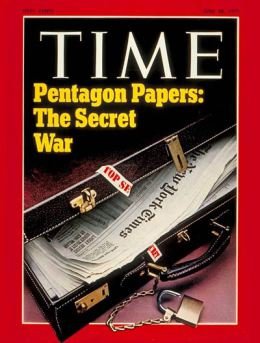

The study came to be known as the “Pentagon Papers.” The full papers were declassified in 2011 and are available on the National Archives website. But when they were leaked in 1971, the papers hit the US public like rolling thunder, a “secret” admission by the government that Vietnam could not be won.

In one document under the “Kennedy Commitments and Programs” section, one analyst lays out the reason the US ultimately decided to get involved: “Faced with a challenge to deal with wars of national liberation, it would be hard to decide that the first one we happened to meet was ‘not our style.’”

In other words, even if a fight seemed hopeless, backing down would not give the Soviet government in Moscow the right impression.

The US government had been sending training advisers and millions of dollars’ worth of supplies and equipment to South Vietnam even before the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964. The Russians and Chinese had turned the North Viet Cong from an insurgent force into a standing army, meaning the US had to do the same in the South or risk looking weak.

But was that a justification for war that the US public would accept?

The report outlined the US involvement in Vietnam over the course of the two decades since World War II.

- The 1954 Geneva Accords, negotiated by the US and essentially ending French rule of Vietnam. The agreement split the country, dividing it along the 17th parallel.

- Its role in the installation of Ngo Dinh Diem as South Vietnam’s president.

- The eventual role played by the CIA in Diem’s overthrow, which ended in his murder.

In each case, the report made clear, the US had doubled down on its previous actions without a visualized end result, let alone a reason for being in Vietnam other than fear of humiliation.

In a subsection of the Pentagon Papers titled “Evolution of the War, Air War in the North: 1965-1968,” the analysts specify a memo sent by Undersecretary of State George Ball to Johnson in late June 1965. “Once large numbers of US troops are committed to direct combat they will begin to take heavy casualties in a war they are ill-equipped to fight in a non-cooperative if not downright hostile countryside,” the undersecretary argues. “Our involvement will be so great that we cannot — without national humiliation — stop short of achieving our complete objectives. Of the likely two possibilities I think humiliation would be more likely than the achievement of our objectives — even after we have paid terrible costs.”

But Ellsberg knew that, once it was delivered to McNamara, the report would never be seen by the public. He believed that the public had the right to know they had been lied to by three different presidential administrations.

Five years after McNamara had commissioned the report, and with no end of the war in sight, Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to Neil Sheehan at The New York Times, which published the first exposé on June 13, 1971, with more sections released in the months after.

The leak proved devastating to President Richard Nixon, who had been elected on a promise to end the war but had then promised to ramp up operations in Vietnam in late 1969 after the Tet Offensive. Recorded phone calls from the White House indicate that Nixon was relatively calm when he first found out about the leak, implying he knew very little about the existence of the Vietnam Task Force. But National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, a supporter of extending the war for political advantage, goaded the president into a rage.

At the end of 1971, Sen. Birch Bayh told the United Press International, “The existence of these documents, and the fact that they said one thing and the people were led to believe something else, is a reason we have a credibility gap today, the reason people don’t believe the government.”

Ellsberg leaked the papers hoping the US would learn to never get involved in another unwinnable war. Ellsberg hoped for no more cover-ups, no more wars with insurgents who could wait the US out, no more wars that dragged on for years with little progress to show and no public support for the efforts overseas.

Though the Pentagon Papers did not end the war, Ellsberg today wonders whether the group that learned the most was politicians with secrets.

“The whistleblowers have much less protection now,” Ellsberg told The Guardian recently. “[President Barack] Obama brought eight or nine or even 10 cases, depending on who you count, in two terms, and then Trump brought eight cases in one term. So sources are much more in danger of prosecution than they were before me and even after me for 30 years.”

Read Next: The Time a MACV-SOG Commando Took On a Force of 100 by Himself

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.