Volunteering to Die: Witold Pilecki’s Firsthand Account From Inside Auschwitz

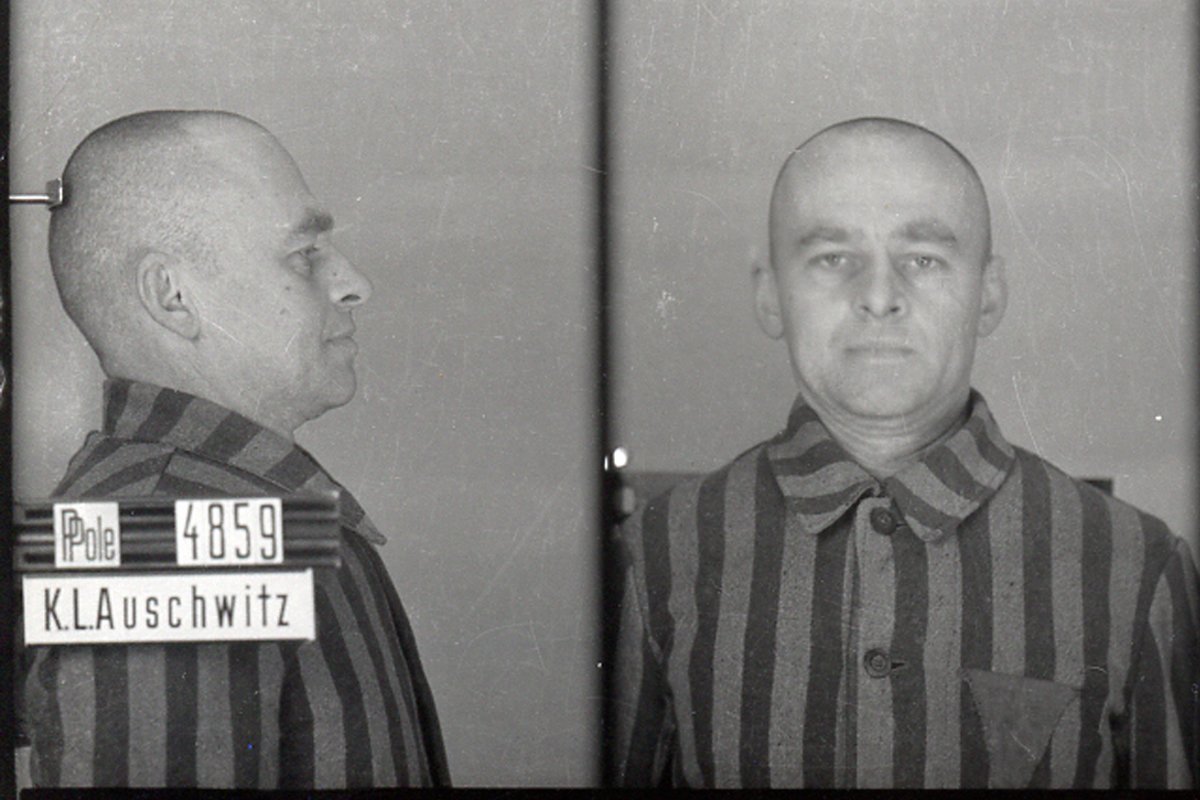

Witold Pilecki inmate No. 4859, photo courtesy of ww2.pl

Have you ever had to make a decision that puts your life in danger? For 39-year-old Polish Home Army Captain Witold Pilecki (pronounced Vee-told Pee-lets-kee), a choice made at dawn on Sept. 19, 1940, put his fate directly in the hands of Nazis. Instead of the smiles usually brought on by brisk autumn mornings, that day was filled with terror as screams echoed off nearby buildings. The second wave of German lorries was unloading and dragging Poles into the middle of the street. Held at gunpoint, the Poles were threatened and scowled upon for being born to the wrong religion or for the inferior blood their bodies contained, now splattered across the curb.

From the sidewalk on the corner of Aleja Wojska and Felińskiego Street, Pilecki volunteered to be captured, knowing that he would be sent to die. The only way he could reach the West with accurate information about the atrocities at Auschwitz was to be there himself.

As an eyewitness to history, Pilecki believed he could provide explicit details of the reality of torture and death at the hands of the Nazis during World War II; to put names and faces on those responsible rather than numbers and statistics from an unreliable document. His undercover mission using the identity of Tomasz Serafiński — a name that was issued in a safe house and later became emotionally significant — to infiltrate and gather intelligence from the inside is hard to plan for and even harder to bring into fruition. The near impossible task of sharing the atrocities hidden beyond the walls and dispelling the effective worldview Nazi propaganda had portrayed could only be accomplished with help — help that he anticipated would come with an inner resistance force called “fives.”

Welcome To Auschwitz: Now Time To Die

For the next several days, alongside thousands of others, Pilecki was herded like an animal by Nazi guards; at night, he slept on the dirty ground under a large spotlight. The prisoners were yanked from the trucks and forced onto transport trains with no food or water. Pilecki huddled together with foreign bodies as if they were toothpicks. Auschwitz sat near a railway junction consisting of 44 parallel tracks south of the Polish industrial town of Oświęcim. It was at the center of Europe where all assets could transport their “undesirables” in fulfillment of Adolf Hitler’s “final solution.”

The January 1940 construction of the camp called for all nearby towns and villages to be evacuated and destroyed. They were then replaced with miles of apartment buildings to house SS soldiers; gas chambers and crematories where men, women, and children were sent to their deaths; and electric barbed-wire fencing with armed guard towers. The Nazi propaganda machine lied to the general public about what was going on there — though that’s not to excuse the civilians in town who pretended not to see the bald and ill-looking people on work details. The complex between Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau alone spanned 472 acres, not including Auschwitz III or the surrounding work sites.

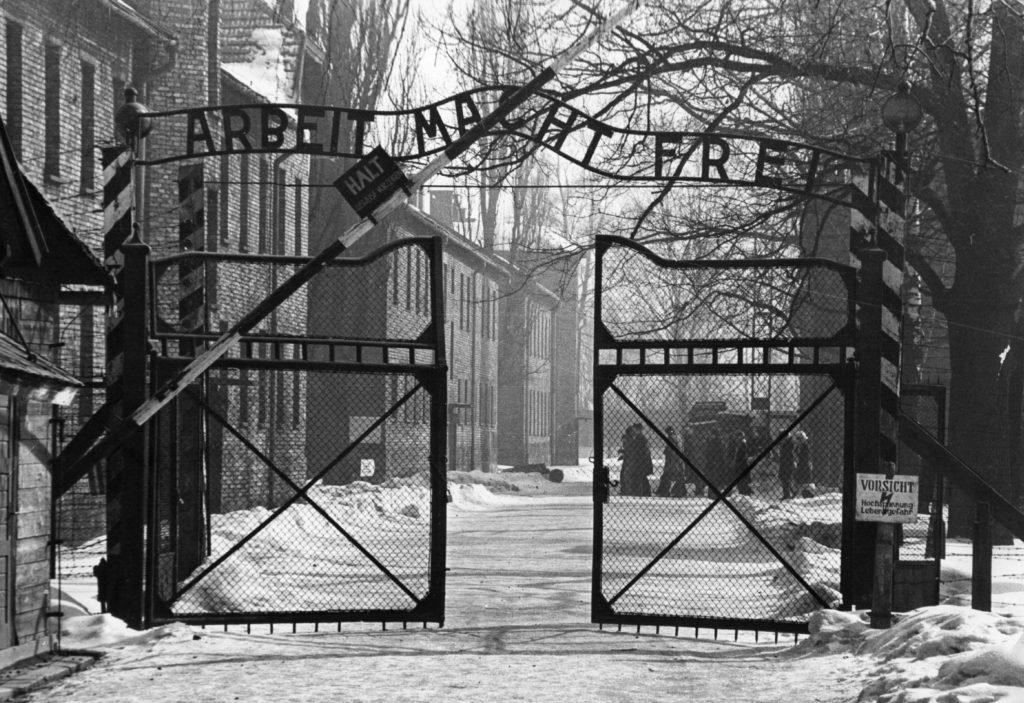

As they approached the infamous front gate that reads “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Sets You Free”), Pilecki observed the confusion; people were dispatched before they even received an inmate number. One Pole was ordered to run and then faceplanted into the dirt; when he was captured, he was limp and perforated with bullet holes. Because of his “escape” the Nazis picked victims at random to shoot in the face as “collective responsibility” to their staged assassination. The SS laughed and joked while their German shepherds barked and chomped their jaws. The Nazis immediately broke their psyches, issuing blows to the head and back with such violence that one hit from a rifle butt or a thick truncheon was all that was needed.

In his memoir, “The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery,” Pilecki describes the condition of his fellow prisoners: “I absolutely see animals here, our language still has no word for such creatures.” Those on the inside learned to refer to this primal condition as muselmänner, the weakened state caused by severe hunger. Their eyes were wide, and any excess fat had been depleted to just skin and bones. Here he was issued his new identity: Auschwitz prisoner number 4859 etched into his skin.

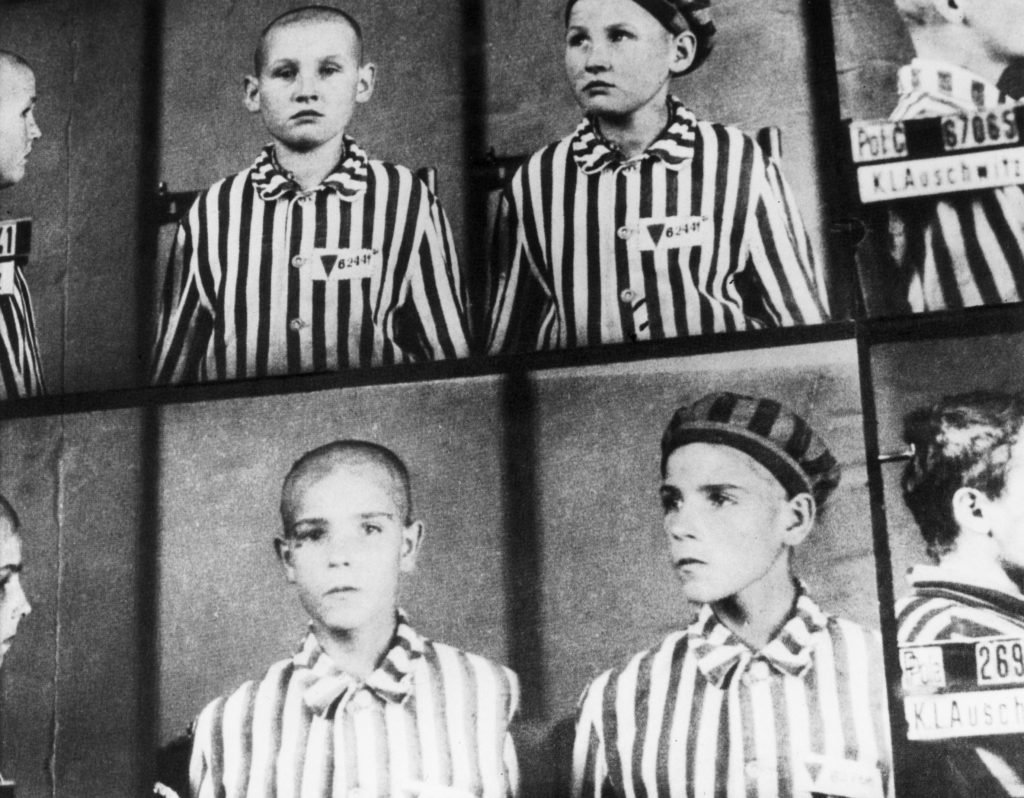

Barefoot, they wore frail blue-and-white striped clothes with a cap like a baker. On their left breasts were colored triangles, or winkels, to distinguish the prisoners to the guards — political prisoners wore red (this is what Pilecki wore), criminals wore green, Jehovah’s Witnesses wore purple, gays wore pink, gypsies and those who refused to work with the Nazis wore black, and Jews wore yellow.

The prisoners either adapted with survival instincts or were murdered for answering basic questions with truth. “The first thing was a question thrown out in German by a striped man with a club: “Was bist du von zivik? [Hey you, what’s your civilian job],” writes Pilecki. “Replying priest, judge, lawyer, at that time meant being beaten to death.”

Years later, when the 100-page Pilecki Report reached Allied commanders, those who read it thought the atrocities were exaggerated. The true horror rationalized by a sane mind could not comprehend as to what unfolded within.

Hell On Earth

Subsections of the camps were broken into Blocks. In the summer, slave labor camps awoke to a gong at 4:20 AM; they were allowed to sleep an hour later during the winter months. Outside the wire, those who went to work sites were called kommandos. SS Fritz Seidler — nicknamed “Bloody Aloiz” — controlled Block 10 and punished them using a method that imaged “death by PE” (physical exercise). Those who could not complete exercises such as squats were murdered. Pilecki credits his athletic background to his resilience, while others who had sedentary professions before the war received the brunt of the torture.

German soldiers recruited “inside the wire,” and those selected gained special treatment. For their cooperation, they were rewarded and tasked with public executions of the helpless and tormenting the resistors. Their numbers stretched through 30, and they were called “kapos.” Inmate No. 1, Bruno Brodniewitsch, was notorious in Auschwitz, but not all were bastards; some were even exploited by Pilecki’s “fives” as they unwillingly participated to save themselves and helped when Nazis weren’t around.

The “fives” were handpicked resistance cells formed by Pilecki. Their aim was to improve their comrades’ morale with organized efforts to bring in additional food from parcels, the collecting of information to be smuggled out of camp, and, although it never materialized, actionable intelligence for the Home Army to launch a rescue mission.

“The kommandos assigned to this task were composed exclusively of Jews and lived for only two weeks. They were then gassed and their corpses were burnt by the other newly arrived Jews, formed into new kommandos, unaware that they were to live for only two weeks and hoped to survive longer.”

Early on, other “fives” weren’t aware of the existence of another cell. This protected them in the event that they were interrogated and tortured — one compromised cell couldn’t bring down the entire organization. Pilecki chose leaders he worked with in Block 5 as a carpenter and evolved the structure like a spider web. Letters were sent home to their relatives that contained secret messages describing the truth of their situation.

Using his wit and observational skills, Pilecki devised a method to make the word “organizing” an acceptable term of camp life, drawing suspicion away from an underground network. “To a certain extent it was our lightning rod,” Pilecki writes. “Here ‘organizing’ meant ‘illicit scrounging.’ Someone would filch some pats of margarine, or a loaf of bread from the stores at night, and it was called ‘organizing margarine or bread.’”

The months ticked by into the spring of 1941 as new arrivals came by the thousands; friends transferred from Pawiak Prison joined the “fives,” and Bolshevik prisoners of war (POWs) were treated as guinea pigs for testing Zyklon B, the cyanide-based pesticide later perfected to use in exterminating the Jews. When electric ovens were approved from Berlin, upwards of 1,000 new arrivals were gassed each day. Tens of thousands of decomposed bodies were buried and had to be dug up by cranes to erase the evidence.

“The kommandos assigned to this task were composed exclusively of Jews and lived for only two weeks,” Pilecki horrifically describes. “They were then gassed and their corpses were burnt by the other newly arrived Jews, formed into new kommandos, unaware that they were to live for only two weeks and hoped to survive longer.”

High-pitched screams of fear were daily reminders of the prisoners’ reality, and minor infractions were met with severe beatings. In the early winter months of 1942, the Nazis were adamant in increasing the construction of gas chambers. At one point, Pilecki writes, “We were building a crematorium for ourselves.”

Cruel SS guards buried people alive — head down with their feet sticking out toward the sky. A sick and twisted form of football pools, writes Pilecki, they took bets on how long it would take until one died. “Clearly he who was closest to guessing how long someone buried in the sand would continue to move his legs before dying, scooped the pot.”

Roll call, which occurred three times a day, involved severe punishments. The Bloody Aloitz, and sometimes Brodniewicz, beat prisoners with a heavy cane or whip 50 or 75 times. After the lashing, the victim had to thank their captors for their beating.

If physical punishments didn’t cripple the prisoners, hunger did: “There were times when one felt oneself capable of cutting off a piece of a corpse lying outside the hospital,” Pilecki writes of the desperation for something more than the cold tea served at meals.

The Wall of Tears

Areas of Auschwitz were designed for those to enter and not return. Pilecki describes a cork-wood-covered wall that was painted black — it was built to absorb bullets and prevent ricochets from bouncing back toward the firing squads. The wall was referred to as the “Wall of Tears” or the “Wall of Death.” Its placement outside linked Blocks 12 and 13; every person that stood next to it, collapsed onto the concrete a bloody corpse.

The Blocks mimicked a slaughterhouse — the smell caused one to gag, and the ground had a flow of dark-red stream passing through the white gutters. The slaughterhouses were meant for pigs, horses, and cows to provide meat to supply feasts for the “superhumans” (senior NCOs). “Not far from the abattoir stood a crematorium where human meat was turned into ash, which then fertilized the fields — the only use for this meat,” Pilecki expresses as a reminder of the unjust persecution.

Human Experiments & Resistance

Nazi doctors performed human experiments on prisoners, and the test results were often thrown out along with the bodies. The Soviet POWs from Siberia faced humiliation as guards mocked and taunted them with laughter as they freezed to death. Dr. Josef Mengle injected twin babies with chloroform after he performed genetic tests to discover how to increase the population of the German race as a means of growing part of their post-war policy.

August Hirt, the head of the department of anatomy at Reich University, selected inmates to assemble Jewish skeletons as a part of the think-tank of Heinrich Himmler’s Ahnenerbe Foundation. Carl Clauberg practiced brutal sterilization techniques on Jewish women and often put them to death to study their autopsies. Men and women were exposed to radiation that killed their reproductive abilities. Pilecki notes that SS Josef Klehr had a “needle list” that tallied as many as 14,000 victims. He poisoned his subjects, causing them to convulse, twitch, and foam from the mouth until they died.

The large pharmaceutical conglomerate IG Farben produced Zyklon B, the cocktail used for the gas chambers. Bayer, known for producing aspirin, bought Auschwitz prisoners on which to experiment with new drugs.

Early on, other “fives” weren’t aware of the existence of another cell. This protected them in the event that they were interrogated and tortured — one compromised cell couldn’t bring down the entire organization.

Those not within Pilecki’s “fives” had other means of subversion. Stanisława Leszczyńska, known as “Mother” inside Auschwitz, helped deliver over 3,000 babies as a midwife. Salamo Arouch fought for his life inside Auschwitz using his fists to appease his captors.

Alongside his mother, his father, and his four siblings, Arouch — the Greek-born, 5-foot-6, 135-pound undefeated boxer — was stripped of his identity when he arrived at Auschwitz. While Arouch, his father, and his brother stood naked, his mother and sisters were sent to the gas chambers. He participated in bare-knuckled brawls against fellow prisoners while Nazi guards placed bets and drank whisky.

“The loser would be badly weakened,” Arouch told People magazine in 1990, “and the Nazis shot the weak.”

Arouch’s brother and father were both executed; the Nazis spared him hard slave labor to fight and win over 200 matches.

Escape

After two and a half years in Auschwitz, Pilecki and others devised plans to escape in 1943. In January, seven bolted through the kitchen at night. They were caught and hanged. The Germans enforced a new policy to counter escapees, vowing to imprison their families, too. The risk grew and a silent war arose. In March, Pilecki faked a hernia to prevent being transported to another concentration camp in order to remain with his tight-knit cell.

Pilecki established emergency routes in the sewers below the camp as a last resort. While on work detail in the local town, the kommandos conducted practice runs to anticipate reaction times, placement of guards, and identify landmarks. A nearby bakery that had bicycles showed promise, but the risk was too costly at that moment. They calculated each option carefully, as failure would result in the immediate death of all known associates.

On the night of April 27, 1943, strong emotions warmed inside them, and Pilecki writes that it felt as if he had wings as his back faced the place that brought so much anguish. Pilecki, Janek (Jan Redzej, inmate No. 5430), and Edek (Edward Ciesielski, inmate No. 12969) arrived at the bakery and swapped with the day shift. In the bakery, they used wheelbarrows to offload the coal into the ovens that heated the bread. The night shift worked well into the morning hours of the next day. The trio separated from the civilian bakers and SS guards around 2 AM, when the notions of sleep were on their minds instead of being alert.

These writings in the Witold Report informed the West of the events of the Holocaust and — without exaggeration — Pilecki estimated that 2 million people were murdered at the camp.

Only one active guard remained, and when he walked into the baking hall, Janek seized the moment. He slipped behind the main door to freedom, took a hook and screw to unlock it, dashed to a coal bunker as the guard returned for a moment, and when he left to check on the ovens, Edek took a quick detour. With a knife, he cut the wire to a telephone that sat next to a sleeping guard’s bed. As the door was exposed, they crashed through it with their gear in tow. At a full sprint, they hauled down the road as eight or nine gunshots rang out behind them.

All changed into civilian attire and masked their identities using hats they stole from the bakery. They crossed bridges and railroad tracks normally patrolled by sentries, but Pilecki assumed they were preoccupied with their Easter festivity hangovers. They hopped across ditches, journeyed through fields, and up and over fences. “Only later did we marvel at how much effort a man can expend when he is running on nervous energy,” Pilecki writes.

The first day of May, a German policeman shot and wounded Pilecki in the shoulder after they refused to stop when they were spotted near a forest headed for Vistula. The next day, Pilecki met the real Tomasz Serafiński, the identity he had adopted while at Auschwitz. The real Serafiński commanded an underground militia in the area. After some confusing back-and-forth of enthusiasm as to who the real Tomasz was, the pair exchanged greetings and pushed for an immediate debriefing of Pilecki’s experiences. These writings in the Witold Report informed the West of the events of the Holocaust and — without exaggeration — Pilecki estimated that 2 million people were murdered at the camp.

He later participated in the Warsaw Uprising and was imprisoned again after the war, convicted of espionage against the pro-Soviet Polish government. On May 25, 1948, Witold Pilecki was executed “Auschwitz-style” despite the work he did bringing to light the evil that was taking place in Nazi concentration camps.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.