Review: ‘We Return Fighting’ and the Black Veterans Who Took Up Arms To Defend Their Communities

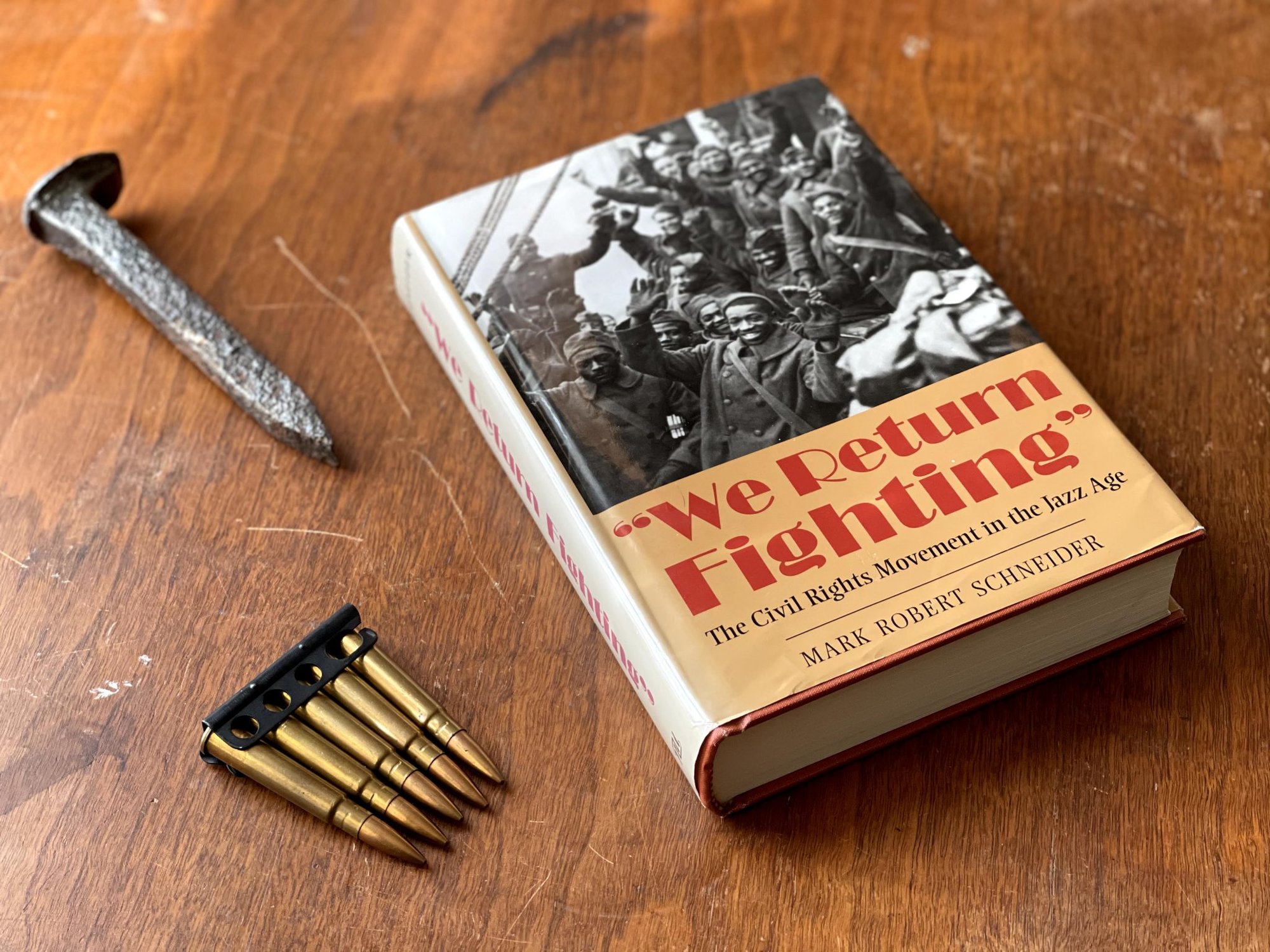

Photo by Mac Caltrider/Coffee or Die Magazine.

“I tire so of hearing people say, / Let things take their course. / Tomorrow is another day. / I do not need my freedom when I’m dead. / I cannot live on tomorrow’s bread.” — Langston Hughes, “Democracy”

Many Americans revisit the incredible story of the Harlem Hellfighters this time of year. Pictures resurface of Black soldiers in French helmets and ships homeward bound with Black troops waving in celebration of victory. There is a long list of must-read books about the famed 369th Infantry Regiment, like Walter Dean Myers’ classic The Harlem Hellfighters: When Pride Met Courage and Max Brooks’ 2014 graphic novel, The Harlem Hellfighters.

Most of the books surrounding the famous all-Black infantry regiment focus on their accomplishments in France. This is no surprise considering the Hellfighters fought longer than any other American regiment, spending a total of 191 days in the trenches around Champagne. They then went on to reach the Rhine before any white regiments. Their battlefield achievements earned the admiration of the French and the respect of the Germans, but even more meaningful was the pride they brought home to Black Americans. Mark Robert Schneider’s 2002 book “We Return Fighting”: The Civil Rights Movement in the Jazz Age is the definitive account of how Black veterans used their wartime experience to protect their communities and advance the rights of all African Americans.

On the cool winter morning of Dec. 15, 1918, Edgar Caldwell, a noncommissioned officer in the United States Army, took the streetcar from Camp McClellan, Alabama, to Hobson City. Sgt. Caldwell, dressed in his military uniform, sat near the front of the streetcar, close to its driver. After a heated exchange of words, the driver and his motorman attacked Caldwell. They beat him with blunt objects and threw him off the back of the streetcar. In full view of other passengers, Caldwell was able to draw his service pistol and shoot his attackers before they killed him. Less than a month later Caldwell was found guilty of murder and executed by the state of Alabama. Despite that Caldwell was clearly acting in self-defense, the court could not see beyond the fact that Caldwell — an African American — had shot two white men.

Caldwell’s fate was not uncommon for the time period. Despite nearly 367,000 African Americans volunteering to serve during the war, white Americans were still largely intolerant of Black troops. Racist stereotypes proliferated, and most commanders held the opinion that Black soldiers were only capable of being laborers. Tropes from the slave era lingered, and popular culture typically portrayed Black troops as lazy, unreliable, and dishonest. Commercial depictions of African American service existed for the sole purpose of entertainment, casting aside all regard for accuracy and decency. Soldiers such as those who belonged to the Harlem Hellfighters changed all that.

Related Article: Harlem Hellfighters: The Forgotten Heroes of World War I

The Harlem Hellfighters, along with the rest of the 42,000 Black soldiers serving in the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, proved to the world they could fight. While falling under the command of the French army, African American infantrymen fought in a string of decisive battles from the Meuse-Argonne to the Second Battle of the Marne. Soldiers such as Henry Johnson, the first American to earn the Croix de Guerre, and Medal of Honor recipient Freddie Stowers permanently cemented African American bravery into American military history. Black troops were celebrated as heroes in France, and received a similar, although short-lived, heroes’ welcome in the United States.

Instead of reiterating what many writers and historians have previously covered about life in the trenches, “We Return Fighting” assumes the reader is already familiar with African American battlefield exploits and instead focuses on the oft-forgotten, yet equally important, role they played upon coming home to America.

The 369th were welcomed home to New York City with a parade through Harlem attended by thousands of cheering Americans. However, this display of gratitude for the soldiers’ service quickly faded. Almost immediately, Black troops stopped being heralded as heroes and instead were subjected to the racist policies still in place across the country. Disheartened by this betrayal, Black veterans took it upon themselves to enact change, and they drove the early days of the civil rights movement forward, decades before names like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X became synonymous with the fight for freedom.

Immediately following the war, the sight of a Black soldier in uniform often ignited a violent response from white citizens who still believed African Americans were unfit to serve, as it did with Sgt. Caldwell. In 1919 alone, white mobs and criminals killed an estimated 76 Black veterans. Lynching became the most common form of domestic terrorism, and soon racial violence spread beyond veterans to all African Americans. In Arkansas, a mob of nearly 1,000 white citizens went on a killing spree that resulted in the deaths of more than 200 African American citizens. The unprovoked violence was largely covered up by false reports of a large-scale “insurrection” of African American sharecroppers.

Police offered little to no protection from racist mobs, and the judicial system failed to provide any legal protection against vigilantes, leaving African American veterans to assume the role of protectors within their own communities. Soldiers took it upon themselves to patrol their neighborhoods and dissuade mob violence. This was the case with William Laney, a Navy veteran, who fired into a pursuing white mob, narrowly escaping with his life. However, these soldiers, trained and experienced in combat, sparked white fear, resulting in a federal ban of African American National Guard units.

During the “red summer” of 1919, when racial violence peaked, African American veterans organized their own defense. They armed themselves with rifles and ammunition and often used vehicles to outmaneuver attacking mobs. The African American veteran-led defense became so large and effective that Congress eventually ordered more than 1,000 troops to enter Washington, DC, and restore order, effectively ending the bloodshed that stained 1919.

The years immediately following the First World War were filled with racial violence in the United States. Newly returned Black veterans felt they had proved themselves as patriots. Having fulfilled their duty in the fight to preserve freedom, they expected to enjoy those same freedoms at home. Instead they were met with increased racism and violence. As seen in the case of Caldwell, they found little protection in the justice system. While standing on the gallows of the Calhoun County prison before a small crowd of spectators, Caldwell used his final moments to address the injustice being inflicted on all African Americans. He purportedly addressed the bystanders:

“I am being sacrificed today upon the altar of passion and racial hatred that appears to be the bulwark of America’s civilization. If it would alleviate the pain and sufferings of my race, I would count myself fortunate in dying, but I am but one of the many victims among my people who are paying the price of America’s mockery of law and dishonesty in her profession of world democracy.”

Moments later he was hung for 12 minutes until finally pronounced dead. It took less than a month from the time Caldwell climbed aboard the Alabama streetcar to the time he was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. Caldwell’s death was one of many black veterans of the First World War who died because of their race. “We Return Fighting” preserves the important story of those veterans whose fight did not end in France.

Read Next:

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.