Final Normandy Dispatch: Free Fall Jump with American Special Operators

Photo by Marty Skovlund, Jr./Coffee or Die.

The weather over Normandy, France, was holding up better than expected. There were clouds, but it wasn’t completely overcast. No rain — well, not yet anyway. Winds were steady but minimal. The conditions weren’t perfect, but America’s most elite warriors don’t need perfect to honor their airborne forefathers who faced a wall of Nazi anti-aircraft fire during the D-Day invasion.

Sixty American special operators were preparing to conduct a military free-fall jump into Iron Mike Drop Zone just outside of Sainte-Mère-Église on Sunday, and all they needed was a peek of the drop zone through the clouds to get the green light. I accompanied them up in the air in a MC-130J from the U.S. Air Force’s 352nd Special Operations Wing, based in Mildenhall, United Kingdom.

The MC-130J was one of dozens of aircraft in the air conducting a seven-nation airborne operation that resulted in over 1,000 paratroopers taking to the skies via both static line and free-fall parachutes. Some say it was the biggest airborne operation in the area since World War II. At a minimum, it would certainly be the most spectacular since then.

The jumpers I was with — all experienced mid-career or senior special operators from the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Army Special Forces — prepared for the jump at Cherbourg – Maupertus Airport near the coast of Normandy. It was a “Hollywood” jump, meaning they would not be jumping with a full combat load. I watched one Air Force Combat Controller stuff a folded American flag down his uniform top for safe keeping during his descent though. Another was wearing an old World War II olive-green uniform jacket for the jump. All were sporting commemorative D-Day 75th Anniversary patches on their sleeves.

The history they were bringing to life by performing the jump in front of a massive crowd was not lost on them. One officer from the 352nd SOW, who requested to remain nameless due to the sensitive nature of his work, explained, “The guys that went into Normandy all those years ago, knowing that this was the invasion that would either win the war, or potentially lose the war …” He paused, searching for the words that could explain how he felt about performing such an important jump. “The fate of the world literally rested on their backs. It’s really humbling to do the same thing, to reenact it, to live it a little bit ourselves.”

There’s an inherent “cool” factor associated with military free fall (MFF). Part of that is due to the fact that most MFF-qualified service members serve in elite units. Another is that launching yourself into the heavens off the back ramp of a cargo plane at dizzying heights that sometimes necessitate supplemental oxygen is just … cool. Although these jumpers would only be exiting at 6,500 feet, the fact that they were dropping into an infamous drop zone made it almost surreal. What they were doing — should the weather hold — was beyond cool.

After a short wait, the jumpers walked up to the rear of their aircraft in a single-file line, ascending the ramp after delivering a fist bump to one of the jumpmasters. Some would take seats in the back, while others would sit on the floor. It had been over 10 years since the last time I flew in a C-130, but I had only ever done static line jumps. Although I wasn’t jumping, this was going to be a radically different experience.

The aircraft taxied out to the runway, and before long we were off and flying. As soon as the jumpmasters could stand up, they were at the small windows looking out at the clouds, trying to see if there were enough holes in the clouds for them to safely exit. So far, it looked good.

“We’re getting out. We’re definitely getting out,” said one Air Force jumpmaster to his Army Special Forces counterpart. The Special Forces NCO agreed. It was going to take more than a bit of cloud cover to stop them from descending into the Norman countryside. Unfortunately, it would be a while before they’d get the opportunity.

One of the static line paratroopers on a different aircraft experienced a parachute malfunction and plummeted to the ground. He sustained life-threatening injuries. A medical helicopter was called in to evacuate him from the drop zone, which delayed further jumps until it was safely out of the area. We circled the drop zone until the all-clear was given some time later.

After many of the jumpers had nodded off to sleep, the crew signaled to the jumpmasters that it was time to start preparing for the jump. The MC-130J’s ramp lowered, flooding the dark interior of the fuselage with light.

The view was stunning. Off in the distance, you could see a CV-22 Osprey flying not far behind. It was also carrying a load of free-fall jumpers. Below, the French countryside appeared as a quilt of greens stitched together by rows of trees. Although we were significantly higher than the D-Day paratroopers were (and they jumped at night), the view was likely not too different than what they saw.

One jumpmaster cinched down the straps on his harness once more. Another stared out the window, continuing to monitor the cloud cover. Some of the jumpers appeared to be practicing hand movements they would need to perform in the air. Despite it being a demonstration jump, they were still exiting a moving aircraft — an inherently risky activity. There was zero room for complacency, even amongst hardened warriors who put their life on the line so often that it has become routine.

I watched as the needle on one Airman’s altimeter began to move.

The aircraft hit turbulence, causing everyone to lurch forward — surely causing an adrenaline spike with the open ramp a few feet away.

The jumpmaster held up a single finger and yelled, “One minute!” before walking down to the edge of the ramp and lowering to one knee to look for the drop zone.

The airmen jumping on this pass all made final adjustments and then settled into a standing position, one foot forward, as if they were getting ready to step off on a run.

The jumpmaster returned and faced his men. “Thirty seconds!”

The command was passed back down the line. It was probably next to impossible for those in the rear to hear the commands over the deafening noise of the engines.

I positioned myself on the hinge of the ramp and made a few final adjustments of my own, ensuring that I was recording and the picture was properly exposed. I briefly debated on the best way to frame the shot.

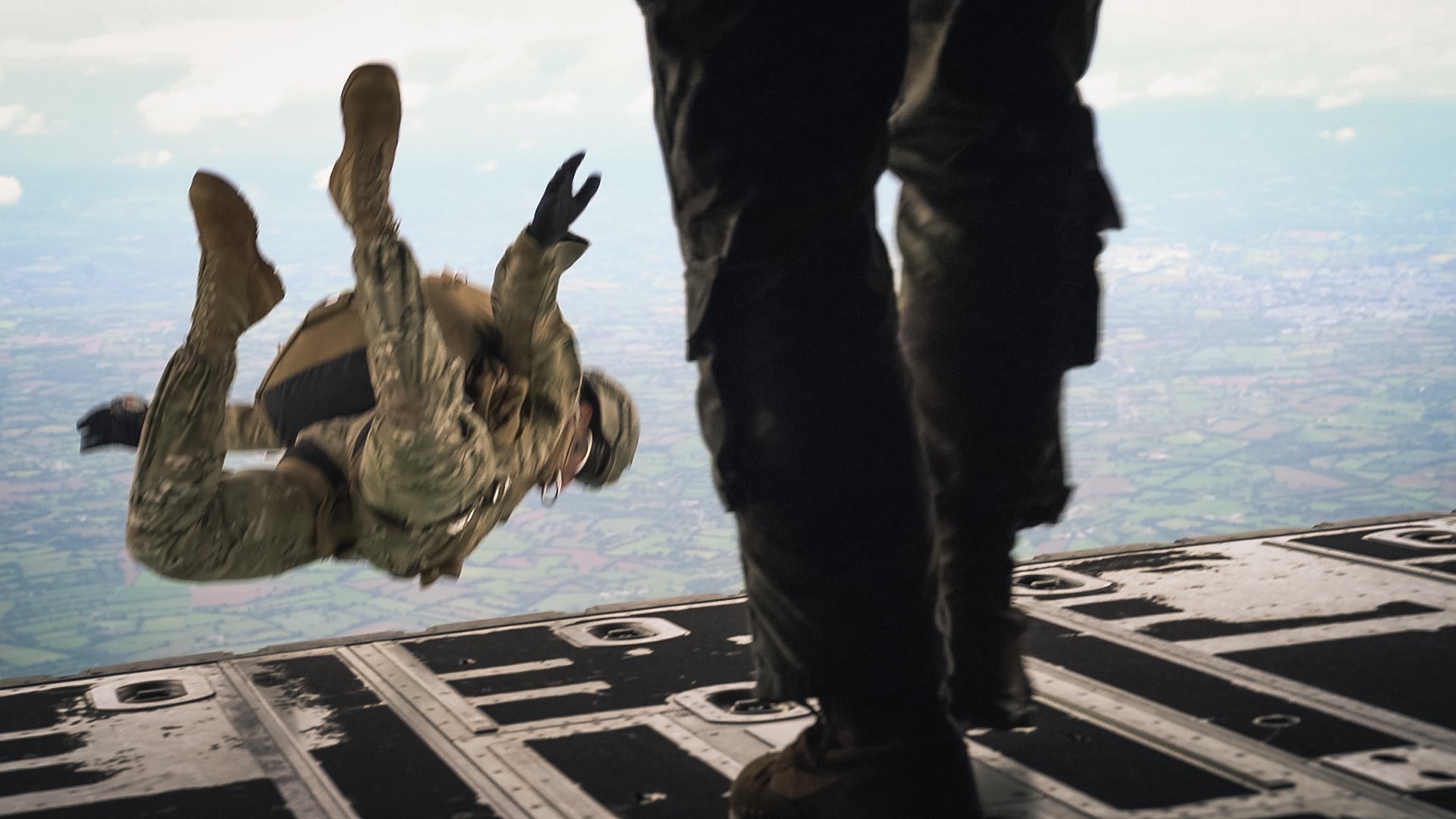

I didn’t see the green light because I was looking at the screen on the back of my camera, but it was clear that it had lit up: clouds or not, the first jumper leapt off the back ramp and into the blue-and-white sky beyond.

All of the U.S. Air Force special operators on board followed suit, each twisting and turning in a different way as they left the aircraft. It was exhilarating to watch. If it wasn’t so real, I would have thought I was dreaming. Military free fall has a beauty (even an art?) to it that static line airborne operations lack. No disrespect meant to my fellow paratroopers, but, visually, static line jumping is utilitarian and industrial, whereas MFF feels boutique. No two jumpers seemed to do the same thing, and the backdrop was stunning.

The first pass went off without a hitch, at least from my vantage point in the aircraft. The next two passes would be for the U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers on board. They repeated the process: one minute, thirty seconds, go. Each pass was as exhilarating as the last.

Shortly after the last jumper departed, we made a hard bank and started what I thought would be a short flight back to the airport. I had no idea the treat I was in for.

The loadmaster told me I could go up into the cockpit and capture footage of the pilots flying, which I happily obliged. The view from the cockpit was great. I thanked them all for having me aboard their aircraft and promised to make sure they looked cool in the video (everything looks cool in slow motion). Before long, they told me they were going to drop the ramp and do some maneuvers and that I should probably head back so I could see them.

I descended back into the fuselage and was greeted with a magnificent view of the blue ocean. It looked like we were only 10 feet off the surface of the water. In reality, we were only slightly higher at 100 feet.

After ensuring that I was properly tethered to the aircraft, the two crew members invited my U.S. Army escort and I down to the lip of the ramp to sit and take in the view. I have ridden in the door of helicopters with my feet dangling out, but doing so from a fixed-wing aircraft in flight is a different experience entirely. I wore a permanent smile.

As if it couldn’t get any better, the CV-22 suddenly dropped into view right behind us. And then I noticed that we were flying right over Pointe du Hoc, the granite memorial standing tall and proud atop the 100-foot cliffs. Shortly after, we were cruising over Omaha Beach. The view of these historic sights from the air was humbling. I’m certain I’ll never forget it.

It wasn’t long before we were headed back to the airport. The men who pilot and maintain this aircraft were nothing short of professional for the duration of the trip, and they left no doubt in my mind that they are among the best in the world at what they do. I thanked them profusely, positive that I would never have such an awe-inspiring experience again.

All of the jumpers on my flight safely made it to the ground. With the dazzling display of fireworks and last call for alcohol later that night outside the Stop Bar in Sainte-Mère-Églis, the celebration of the 75th anniversary of D-Day came to a close. The town square was filled with American, British, and German paratroopers who ranged from young infantryman in the 82nd Airborne Division to elite special operators with double-digit deployments under their belts.

A light rain began to fall, and all present began singing the words to “Blood Upon the Risers.” Paratroopers aren’t going to let a little bad weather get in the way of a good time. As I walked toward where my car was parked, I could still hear the echoes bouncing through the hallowed streets, “Gory, gory, what a helluva way to die! Gory, gory what a helluva way to die …”

Editor’s Note: The original version of this article stated that the aircraft was a C-130. It is actually the MC-130J model, and the article has been updated to reflect this.

Marty Skovlund Jr. was the executive editor of Coffee or Die. As a journalist, Marty has covered the Standing Rock protest in North Dakota, embedded with American special operation forces in Afghanistan, and broken stories about the first females to make it through infantry training and Ranger selection. He has also published two books, appeared as a co-host on History Channel’s JFK Declassified, and produced multiple award-winning independent films.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.