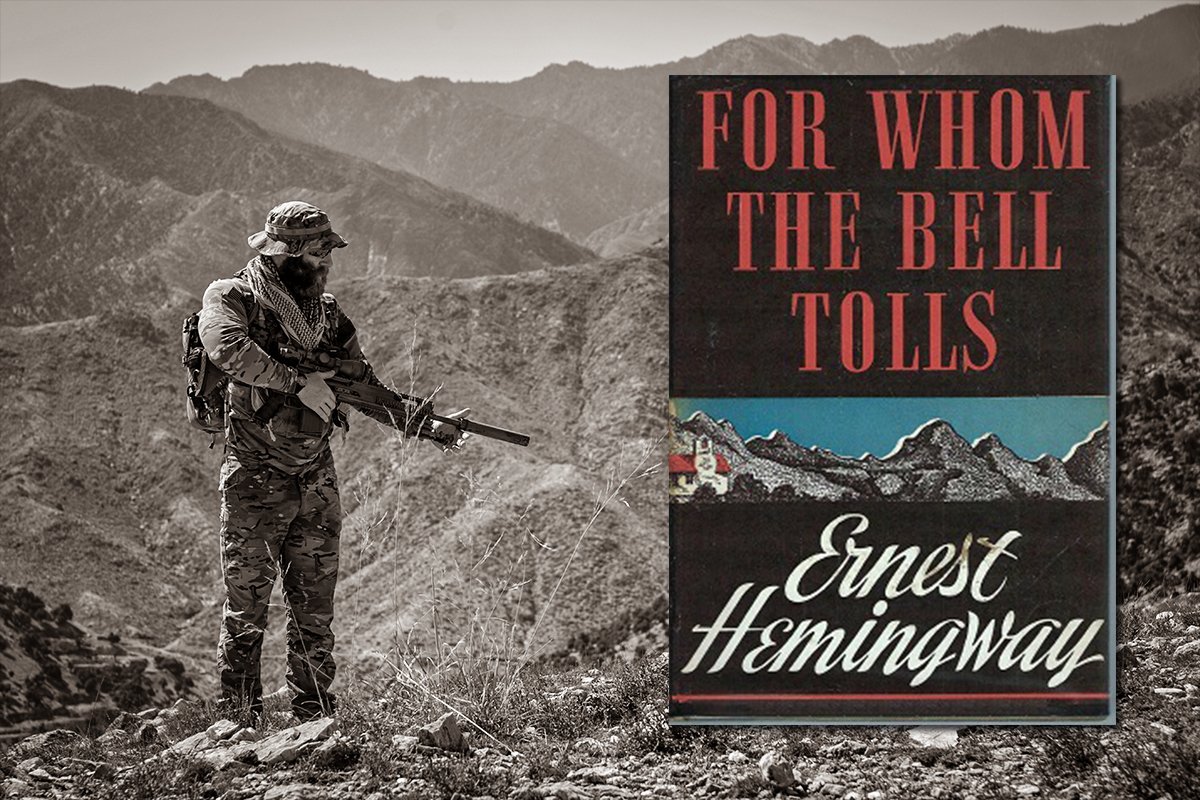

How Hemingway’s ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ Provides Insight Into Modern Special Forces

The U.S. Army’s Special Forces, sometimes known as “Green Berets,” are an elite special operations force (SOF) tasked with many types of missions, from direct-action raids to complex reconnaissance and gathering human intelligence on the ground.

However, like other SOF, they have a primary mission that separates them from the rest: infiltrating hostile territory, training indigenous personnel who are sympathetic to their cause, and — in some cases — fighting alongside them. In order to accomplish this mission, they must have a breadth of knowledge ranging from customs and culture to various types of weaponry (which is often not ideal among indigenous groups in a war zone) to in-depth language training.

Although the words “Special Forces” are not used, Ernest Hemingway illustrates the essence of a Special Forces operator in his acclaimed novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” Published on Oct. 21, 1940, the novel sheds light on some of the nuances of the SF mission. The protagonist, Robert Jordan, isn’t there to raise a small army of his own, become the face of some revolution, or save the day single-handedly. He is a dynamiter with a significant amount of combat experience sent to blow up a single bridge on a specific day; just one small piece in a much larger war effort, working quietly and without much fanfare.

Hemingway, of course, took a few artistic liberties that would probably not apply to the Special Forces as we know them today — for example, Jordan is conducting a solo mission, whereas SF teams usually work in small groups. There is also a love interest in the novel, which is atypical in these types of scenarios.

The entire novel revolves around his fairly simple and straightforward mission:

“[T]he problem of the bridge was no more difficult than many other problems. He knew how to blow any sort of bridge that you could name and he had blown them of all sizes and constructions. There was enough explosive and all equipment in the two packs to blow this bridge properly even if it were twice as big as Anselmo reported it, as he remembered it when he had walked over it on his way to La Granja on a walking trip in 1933, and as Golz had read him the description of it night before last in that upstairs room in the house outside of the Escorial.”

Jordan’s mission embodies the “special” part of Special Forces. It is in the midst of the Spanish Civil War, a few years before the United States would enter World War II, and he is working alongside the Russians in a paramilitary group to quell the fascist side. SOF units are often in countries long before the U.S. invades, assisting forces who share a common enemy and setting the stage for future, larger U.S. operations.

Robert Jordan does not have an open line of communication with the assault force for which he is blowing up the bridge. If they change the plan, if they attack early or somewhere else, if anything deviates at all, he will have no way of knowing. He is cut off and on his own, part and parcel for that type of mission. While this was a partial reality of any warrior in the 1940s, it is still often true for SF operators to this day.

There is a moment when it becomes imperative — for the mission and for the lives of those he is fighting alongside — that Jordan relay some information up his chain of command. He sends runners on what becomes an agonizing series of chapters. The runners have no choice but to walk to the front lines (they are behind enemy lines, after all), hope they are not fired upon, speak to noncommissioned officers (NCOs) on the line, and work their way up through the Russian bureaucracy (which almost gets them killed several times) simply to deliver a message to one of the top generals.

Imagine pulling guard on a forward operating base (FOB) in a dangerous part of Afghanistan when two Afghan men with rifles approach, claiming to work for an SF group miles and miles away — a group you didn’t know was operating out there. Imagine how difficult it would be for them to get in a room with your commanding officer, let alone an entire strike force. While modern SF operators have better lines of communication than the fictitious Robert Jordan, it goes to show how working out in the boonies with no direct lines of communication to the rear can cause all sorts of problems.

He heard a bolt snick as it was pulled back. Then, from farther down the parapet, a rifle fired. There was a crashing crack and a downward stab of yellow in the dark. Andrés had flattened at the click, the top of his head hard against the ground.

“Don’t shoot, Comrades,” Andrés shouted. “Don’t shoot! I want to come in.”

“How many are you?” some one called from behind the parapet.

“One. Me. Alone.”

“Who are you?”

“Andrés Lopez of Villaconejos. From the band of Pablo. With a message.”

“Have you your rifle and equipment?”

“Yes, man.”

“We can take in none without rifle and equipment,” the voice said. “Nor in larger groups than three.”

“I am alone,” Andrés shouted. “It is important. Let me come in.”

He could hear them talking behind the parapet but not what they were saying. Then the voice shouted again, “How many are you?”

“One. Me. Alone. For the love of God.”

They were talking behind the parapet again. Then the voice came, “Listen, fascist.”

“I am not a fascist,” Andrés shouted. “I am a guerrillero from the band of Pablo. I come with a message for the General Staff.”

“He’s crazy,” he heard some one say. “Toss a bomb at him.”

“Listen,” Andrés said. “I am alone. I am completely by myself. I obscenity in the midst of the holy mysteries that I am alone. Let me come in.”

Of all of the special operations units, Special Forces is the most social, for lack of a better term. They are constantly working with militants, soldiers, or guerilla fighters from other countries, training with them, and sometimes fighting alongside them. Building relationships, earning trust, and gaining respect is a core tenet of their mission.

This more human side of things is depicted in “For Whom the Bell Tolls” as well. Jordan has a certain romantic idea about the people of Spain, and he had lived there before he volunteered to fight. He knows the language well, and he is genuinely interested in the hill-dwelling, anti-fascist guerrillas that he fights next to.

However, he’s not wearing rose-tinted glasses. Jordan does not rave about their perfection; he simply sees their differences, many positive and some negative. He notes the shortcomings of each individual, as well as their culture as a whole. Most notably in the military sense, he has to teach them practical things and make do with their tactical shortcomings.

At one point in the novel, Jordan and his most trusted local friend, Anselmo, meet an untrustworthy local fighter. “They are wonderful when they are good, he thought. There is no people like them when they are good and when they go bad there is no people that is worse. Anselmo must have known what he was doing when he brought us here.” Jordan’s constant fluctuation between trust and mistrust is apparent.

Any Special Forces operator could likely tell you a story about some frustration they had in teaching foreign nationals how to conduct themselves in combat. Be it in the midst of a war in Afghanistan or a friendly training exercise in Thailand, there is always going to be a disconnect between well-trained soldiers and the people they train — some may have only fired a rifle once or twice in their lives, but will be expected to handle daunting tasks during a mission with confidence.

“You have an automatic rifle?” Robert Jordan asked.

Sordo nodded.

“Where?”

“Up the hill.”

“What kind?”

“Don’t know name. With pans.”

“How many rounds?”

“Five pans.”

“Does any one know how to use it?”

“Me. A little. Not shoot too much. Not want make noise here. Not want use cartridges.”

“I will look at it afterwards,” Robert Jordan said. “Have you hand grenades?”

Plenty.

“How many rounds per rifle?”

“Plenty.”

“How many?”

“One hundred fifty. More maybe.”

“What about other people?”

“For what?”

“To have sufficient force to take the posts and cover the bridge While I am blowing it. We should have double what we have.”

“Take posts don’t worry. What time day?”

“Daylight.”

“Don’t worry.”

“I could use twenty more men, to be sure,” Robert Jordan said.

“Good ones do not exist. You want undependables?”

“No. How many good ones?”

“Maybe four.”

“Why so few?”

“No trust.”

“For horseholders?”

“Must trust much to be horseholders.”

“I’d like ten more good men if I could get them.”

“Four.”

This dialogue between two male characters, both professionals, demonstrates that while they understand the gravity of the situation, one is clearly more knowledgeable than the other. Jordan’s presence in the area is an asset to the war effort at large, but he’s also a huge asset to the local fighters in the conflict.

“For Whom the Bell Tolls” doesn’t shy away from the nuances of conflict. When in the midst of combat, it can be difficult to take a step back and understand its complexity; when we are invested in it, we tend to see things in black and white. However, SF operators have the unique perspective of seeing multiple foreign conflicts from the outside, and then they subsequently involve themselves in those conflicts. They are privy to the nuances of wars around the globe, and the human toll those wars exact.

There is a chapter where a woman named Pilar recounts the killing of fascists in a small Spanish village. Like the other anti-fascists, she is there to fight and even kill those who stand against them. But it is one thing to fight on a battlefield and another thing to see men who only casually followed fascist politics be brutally executed simply based on that title. Pilar remembers as they were led out, one by one, and beaten to death by angry villagers.

The villagers who did the killing were regular people caught up in the blood-lust that human beings are so compelled toward during times of violence.

“Because the people of this town are as kind as they can be cruel and they have a natural sense of justice and a desire to do that which is right. But cruelty had entered into the lines and also drunkenness or the beginning of drunkenness and the lines were not as they were when Don Benito had come out. I do not know how it is in other countries, and no one cares more for the pleasure of drinking than I do, but in Spain drunkenness, when produced by other elements than wine, is a thing of great ugliness and the people do things that they would not have done. Is it not so in your country, Inglés?”

“It is so,” Robert Jordan said.

It’s one thing to visit a country, it’s another to live there, and it’s yet another to work with the locals. Further still, one gains a deep understanding of a people when they fight alongside them. The men of the U.S. Army’s Special Forces have an intimate understanding of this, and if you want to take a peek at what that might feel like — beyond a brief article or Department of Defense description of duties — then take a trip through Ernest Hemingway’s For “Whom the Bell Tolls.”

Luke is the author of two war poetry books, The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence, and a post-apocalyptic novel, The First Marauder. He grew up in Pakistan and Thailand as the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and deployed to Afghanistan on four combat deployments. Now he owns and operates Four Hawk Media, a social media-focused marketing company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.