Operation Alert: The Civil Defense Drills That Prepared America for Nuclear Attack

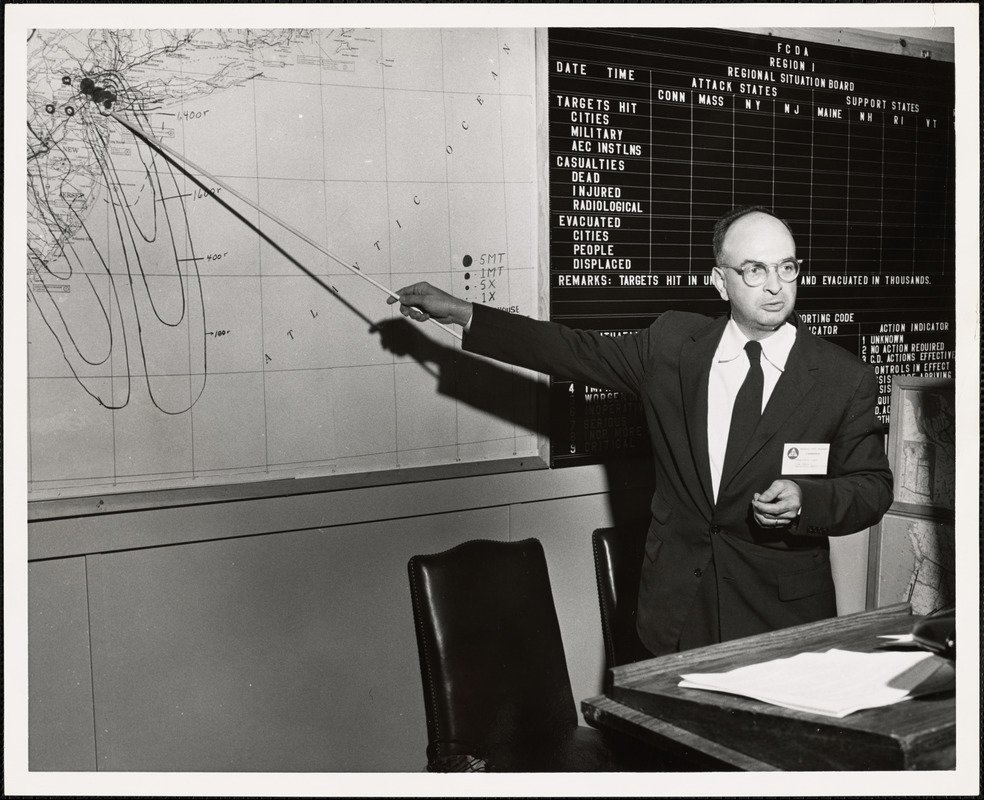

An instructor at Harvard teaching a lesson on Operation Alert, 1956. Photo courtesy of https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:h128rf91t

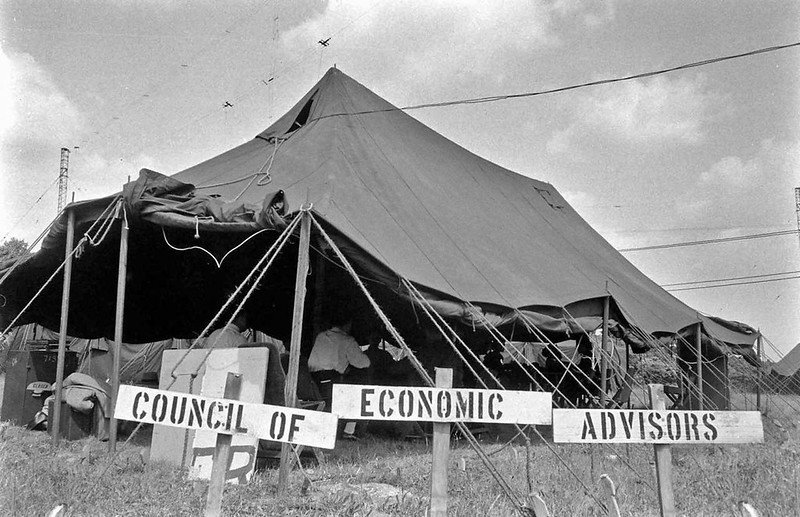

“Red alert, attack imminent,” a warning flashed into the headquarters of the civil defense network. Chrysler air raid sirens came to life as more than 200 cities nationwide participated in the biggest air raid drill ever attempted. President Dwight D. Eisenhower left the oval office en route to an emergency tent city outside the capital, and key military officials were airlifted from the Pentagon to clandestine control centers. Ten thousand government employees evacuated their homes and offices in Washington to participate in the five-day study to ensure that the United States had an effective plan to respond to the fears of what they considered an inevitable nuclear strike.

The United States had just used two nuclear weapons during World War II, and in the wake of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Americans feared the same weapon could be used on American cities such as New York City, Boston, San Francisco, or Dallas. On June 15, 1954, in the midst of the Cold War between the U.S. and Soviet Union, the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) launched Operation Alert. The annual event that continued through 1961 gripped the nation and turned Times Square into a ghost town as taxi cabs and pedestrians vacated the streets for shelter. Schools instructed their students to follow “duck and cover” drills for 15 minutes in the event society faced an impending nuclear attack.

The drills were intended to educate rather than scare. The news media played an integral role in bringing awareness to new developments and wrote fictitious stories as if they were covering the “breaking news” in real time.

“In a recapitulation tonight, the Federal Civil Defense Administration estimated assumed casualties at 5,000,000 killed and almost 5,000,000 injured,” wrote the New York Times. “It also estimated that 10,000,000 persons had been made homeless, creating serious welfare problems.”

The sentiments of an upcoming war with the Soviet Union during the 1950s also had convincing films, one that called the “take to the hills” mantra and evacuation of American cities an act of treason. A film titled “Our Cities Must Fight” released in 1951 covered what the average citizen should do if their neighborhood became a nuclear holocaust — including instructing citizens to not evacuate but stay behind as an insurgency force to fight Soviet invaders.

Those who didn’t participate in Operation Alert were threatened with a $500 fine and possibly up to a year in prison. The Deputy Director of the FCDA described the exercise as “not a drill, but a show,” and despite his attempts to portray the drill as propaganda aimed toward the Russians, he was fired immediately.

The CIA even monitored the events and, in one report, tested communications between emergency relocation sites and evaluated damage assessment data as they prepared for whether their officers would have to work intelligence at home instead of abroad. They went as far as documenting the type of burst from the explosion, the number of casualties and displaced citizens in the region, and summaries of actions taken to assist “targeted” cities in recovery. St. Louis was used as a pilot program that covered a wide range of intricacies from stockpiles of medical supplies to whether the water supply or important infrastructure such as the power grid had been affected.

The U.S. government took the information from their March 1, 1954, hydrogen bomb test in the Bikini Atoll, which showed the fallout spread 7,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean, and applied that information to their exercise. Remarkably, 13 cities were not given advance notice of the drill and had to respond as if a real-world crisis erupted before them.

“We are here,” Eisenhower said in an address to the nation, “to determine whether or not the Government is prepared in time of emergency to continue the function of government so that there will be no interruption in the business that must be carried on.”

The final civil defense Operation Alert drill occurred in 1961 before it was canceled due to dwindling public support and increased anti-war protests.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.