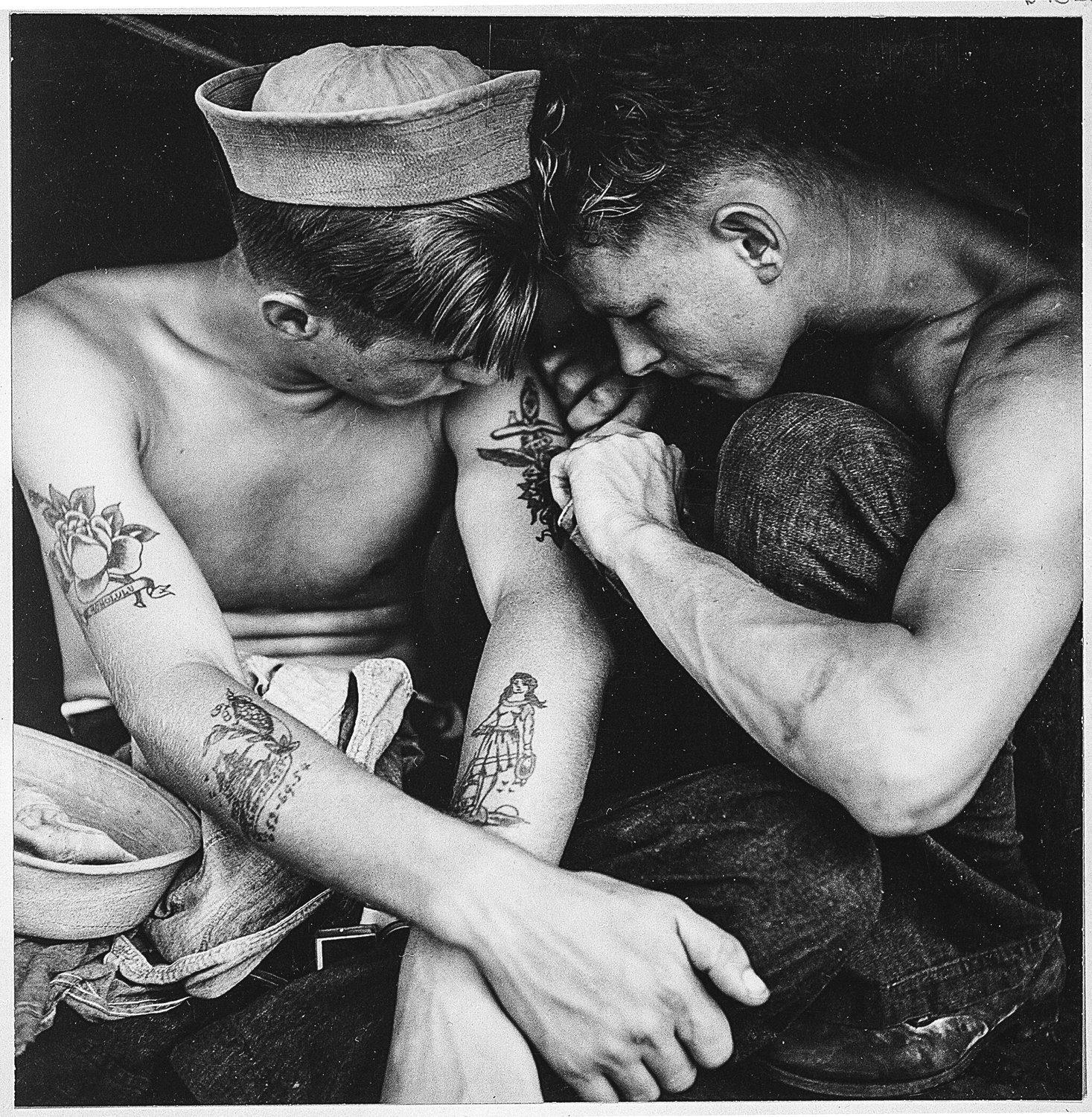

Much-tattooed sailor aboard the USS New Jersey, WWII. Photo courtesy of the US National Archives and Records Administration.

Danny O’Neel, Army veteran and co-owner of Folsom, California, tattoo shop Kinetic Ink, laughed when asked about the most common military tattoo request at their shop.

“A flag,” he said.

In reality, service members and veterans of the armed forces have as much variety in their tattoos as do civilians. But it is fairly common to see tattoos representing or commemorating their time in the service. Indeed, tattoos have been a rite of passage for service members across cultures for more than 2,000 years.

“A lot of guys definitely got their first tattoos in the military, articulating something around their service, where they’ve been to, their MOS number, whatever it may be,” tattoo artist Andre Forest told Coffee or Die, estimating that 80% to 90% of the Marines in his combat engineer unit had tattoos.

Sonny Batten, tattoo artist and co-owner of Kinetic Ink, loves working with service members and veterans to design meaningful artwork.

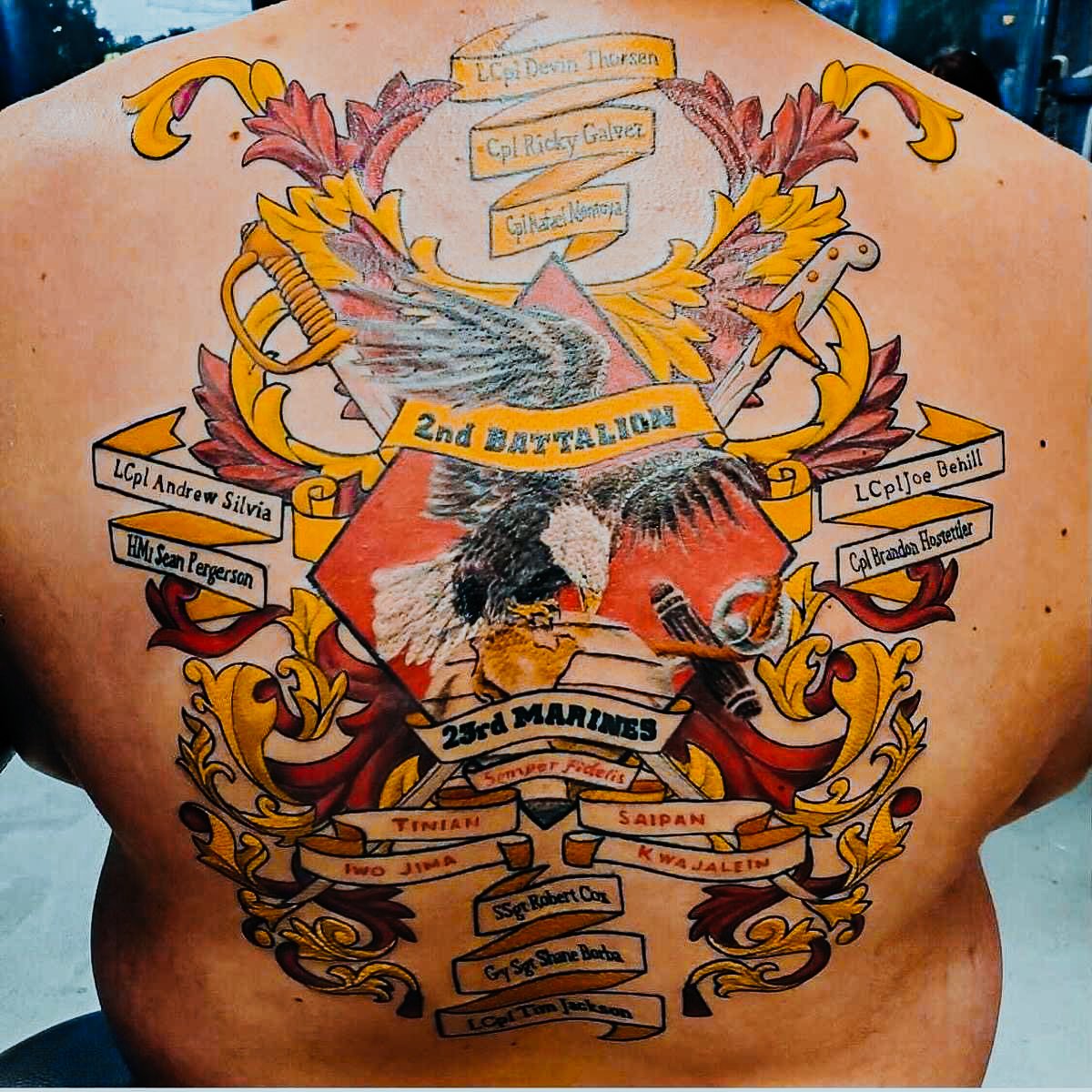

“There are so many different things that people do to communicate a piece of their story — it's just for them to be like, hey, you know what, I made it through this. I'm still alive, I'm still breathing,” Batten said. “They’re covering some scars with another scar, so to speak, but something beautiful, something that can help bridge that pain — a stepping stone to help them move forward.”

An Ancient Tradition

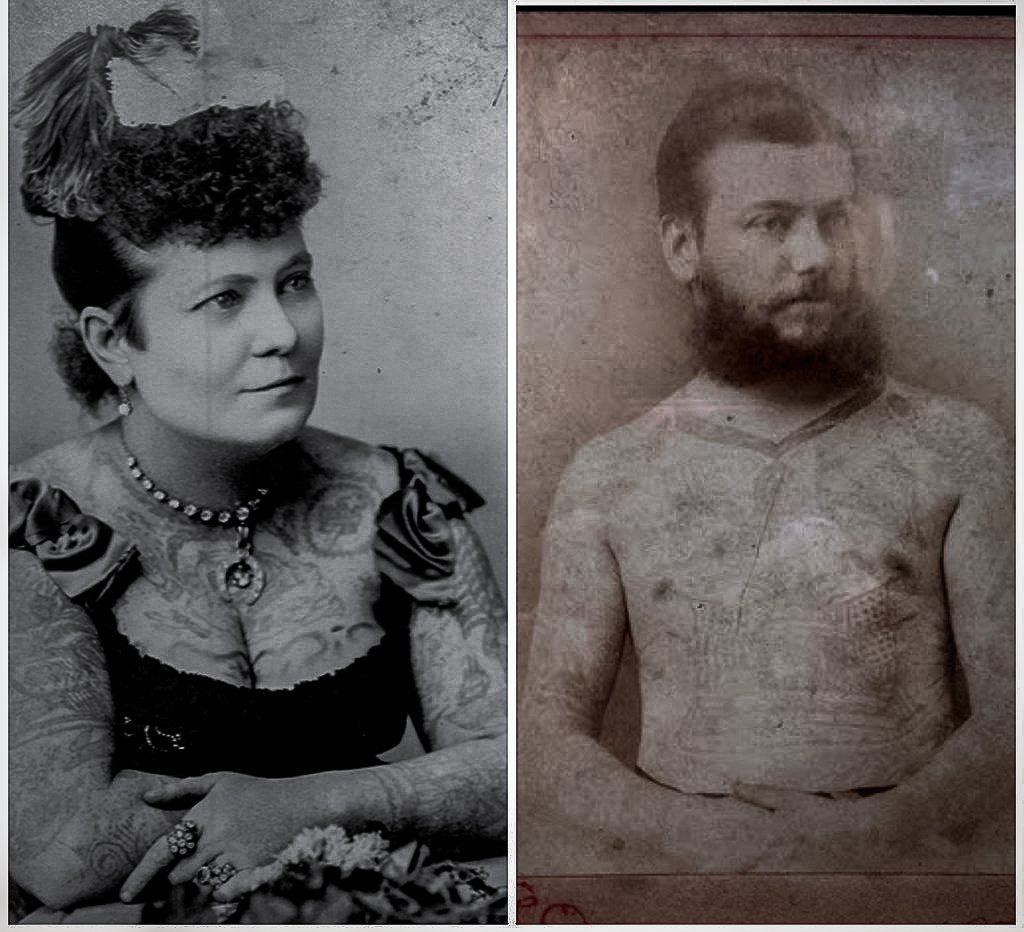

Nora Hildebrandt, left, and Capt. Harry DeCoursey, right, were two clients of Martin Hildebrandt, the first professional tattoo artist to open a shop in America. Photos courtesy of Michelle Myles of Daredevil Tattoo/Wikimedia Commons.

The earliest tradition of military tattoos is found in Roman culture. According to the Roman author Vegetius, legionnaires were tattooed with a symbol of their unit; the writer Aetius of Amida says in his work Medicae artis principes that the tattoo was placed on the soldier’s hand. In the movie Gladiator, soldiers are tattooed with the letters “SPQR,” which stands for Senatus Populusque Romanus (“The Roman senate and people”).

However, no one knows what the tattoos actually looked like. Scholar Lindsay Allason-Jones believes that it may have been an eagle or a symbol specific to a soldier’s legion.

Some of the warriors that Roman legionnaires battled were also tattooed. When the Romans arrived in the British Isles, they were confronted by men covered in tattoos, whom they fittingly referred to as Pictii, or “the painted ones” — they are now known as Picts. Very little is known for certain about the Pictish culture, including whether the blue tattoos that covered their bodies were permanent. But multiple Roman sources, including Julius Caesar, told of howling naked men with head-to-toe ink fighting fiercely against the invading legions.

The art of tattooing waned dramatically in Western culture after Pope Hadrian I outlawed the practice in 787 A.D. But, on the other side of the globe, tattooing was widespread in the Polynesian islands.

The Maori tribes of New Zealand called it “ta moko,” and specific motifs were used to designate warriors and rowers. The Maori used combs made of bone, tortoiseshell, or mother-of-pearl. The teeth of the combs were soaked in candlenut charcoal ink. The comb was placed against the skin and tapped with a mallet to the rhythm of drums, flutes, and conch horns.

The voyages of British Capt. James Cook to Polynesian islands such as Tahiti and Hawaii introduced a generation of sailors to the art of tattoos. Indeed, it was Cook who first used “tattoo,” a bastardization of the Tahitian word “tatau,” to describe the practice in English. Sailors returned to Britain with ink that commemorated their travels.

In The US Military

An eagle, globe, and anchor back piece in traditional flash style. Screenshot from YouTube.

American sailors adopted the practice of tattooing from the British, with many inking their citizenship onto their bodies to prevent being illegally recruited by the British Navy. According to tattoo historian Albert Parry, sailors began tattooing patriotic symbols on themselves. “It was the old striving to frighten the enemy with magic representations of the tribe’s invincibility,” Parry wrote.

The first tattoo shop in the US was founded by a German immigrant named Martin Hildebrandt. Hildebrandt joined the US Navy and served from 1846 to 1849 on the USS United States, where he learned to tattoo from another sailor. During the Civil War, he served in the Army of the Potomac and traveled from camp to camp offering military tattoos. Men from more units learned the art, and tattooing rapidly became as widespread among soldiers as it had been among sailors.

Tattoo parlors began to proliferate in port towns. Contemporary historian Wilfrid Dyson Hambly estimates that 90% of American sailors had tattoos by the end of World War I.

Forest, a tattoo artist who served two tours in Afghanistan, idolized the influential tattoo artist known as Sailor Jerry. “I looked up to Sailor Jerry as a kid, not knowing he served in the military, actually,” said Forest, who professionally uses the name Tatu Dreezy. “I thought he was just some guy that drew badass tattoos and drink liquor all day.”

Original flash artwork of Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins, in ink and watercolor. Photo by Rob Corder.

Sailor Jerry was born Norman Collins, and he joined the Navy in the 1930s. After leaving the service, he set up a tattoo shop on Hotel Street in Honolulu. He was in contact with Japanese master tattooers, and ironically used many of their techniques to decorate US service members with patriotic imagery in the wake of the bombing at Pearl Harbor.

While military tattoos remained popular throughout the 20th century, military leadership began to push back during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Waivers for out-of-regs tattoos increased during the Iraq War surge when the military needed to fill billets, but the blowback was severe as troop numbers wound down.

While many military tattoos were grandfathered in, policies across branches tightened, with the possibility of unauthorized ink triggering a dishonorable discharge.

Former Sgt. Maj. of the Army Raymond Chandler was particularly outspoken on the subject.

“The Army is a professional organization,” Chandler said in 2013, as a more stringent policy went into effect. “It is a uniformed service where the public judges a soldier’s discipline in part by the manner in which he or she wears the uniform, as well as by personal appearance.”

Current Regulations

This back piece, created by Sonny Batten of Kinetic Ink, has the names of 13 deceased Marines. Some of them died in Iraq; many more died after making it back home. Photo by Kinetic Ink Tattoo.

Much as the Navy led the vanguard of military tattoos in the mid-19th century, they were also ahead of the curve in updating their tattoo policies to better accommodate a wide range of recruits. The most recent policy change in 2016 removed all restrictions on size and number of arm, leg, and hand tattoos. It also permitted a single neck tattoo with a 1-inch radius. The only areas with a blanket proscription are the head, face, and scalp.

The Marines were the next service to serve up a policy revision in the fall of 2021. “The tattoo policy over the years has attempted to balance the individual desires of Marines with the need to maintain the disciplined appearance expected of our profession,” Marine Corps Bulletin 1020 reads. “This Bulletin ensures that the Marine Corps maintains its ties to the society it represents and removes all barriers to entry for those members of society wishing to join its ranks.”

Not quite as lenient as the Navy, Marines are barred from having tattoos on the head, neck, and hands. All other areas of the body are fair game. Prior to this, Marines had been barred from having multiple tattoos on forearms or lower legs, as well as any ink on the elbows or knees.

An interpretation of the bone frog tattoo with color. Only Navy SEALs can get this tattoo, excepting unusual circumstances. Photo courtesy of tattoo artist Joey Nobody.

The Marines took pains in their bulletin to point out that “there are future career implications regarding the application of tattoos.” Tatu Dreezy, who had two waivers for tattoos outside of regulations, is glad to see the stigma changing.

“They always preached to us about troop welfare and troop well-being — as long as it doesn’t look trashy, go for it,” he said. “Don’t slap it on your face or your forehead, and I think you’re okay. We’re losing that generation that frowned upon tattoos.”

The Army updated their policy in June 2022, and now allows for a tattoo 1 inch in diameter on each hand, a tattoo 1 inch in diameter behind each ear, and a tattoo 2 inches in diameter on the back of the neck. It also now allows unlimited tattoos between fingers as long as they are not visible when the fingers are pressed together.

The only areas still banned are the sides of the neck, the face, visible fingers other than one ring on each hand, and the inside of the mouth or ears.

A US soldier showing off her military tattoos. US Army photo by Lara Poirrier.

The Air Force created its own updated policy this spring, allowing 1-inch tattoos on each hand and one tattoo on the neck anywhere around the back from ear to ear. Space Force Guardians had previously been permitted a neck tattoo, but the new policy creates uniform standards across the branch. The Air Force already allowed tattoos on the chest, back, arms, and legs. Chest and back tattoos are not allowed to peek out of uniform collars.

“It’s important that we continuously look at policies that may be a barrier to service for many young Americans,” Leslie Brown, chief of public affairs for the Air Force Recruiting Service, told Coffee or Die in an email. “We are recruiting today’s generation, not my generation who joined more than 30 years ago, where a tattoo may have been taboo then but is a societal norm now.”

While the specifics vary across branches, there is one commonality: Military tattoos may not contain offensive, hateful, or extremist words or images.

Read Next: The Meaning Behind the Bone Frog Tattoo For Navy SEALs

Maggie BenZvi is a contributing editor for Coffee or Die. She holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Chicago and a master’s degree in human rights from Columbia University, and has worked for the ACLU as well as the International Rescue Committee. She has also completed a summer journalism program at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. In addition to her work at Coffee or Die, she’s a stay-at-home mom and, notably, does not drink coffee. Got a tip? Get in touch!

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.